The War in Cork

Civil resistance can be defined as a popular protest taken to demonstrate opposition to a government or its policies. In addition to campaigning for better conditions and wages for workers, the Irish Labour Movement also organised acts of civil resistance in support of the Republican movement during the War of Independence. Two of these, the General Strike and the Munition Strike of 1920 would have a significant impact on the conflict.

(Above) Military historian Gerry White gives an overview of hostilities during the Irish War of Independence

On 5 April 1920, over thirty republican prisoners in Dublin’s Mountjoy Prison commenced a hunger strike to secure political status. By 9 April, ninety prisoners were fasting. In an effort to support the prisoners, the Irish Trade Union Council called a general strike for 13 April. The strike lasted two days and, aside from the unionist dominated areas of Ulster, the entire country came to a standstill. The strike achieved its objective as it led to the release of republican prisoners all over the country. On 20 May 1920, the largest campaign of civil resistance in the war commenced when railwaymen in Dublin refused to work on trains carrying munitions or armed British soldiers. Railwaymen in other parts of the country soon followed suit and they were joined by dockers. The strike, which lasted until 21 December 1920, led to the closure of hundreds of kilometres of railway lines and the dismissal of 15,000 railway workers and hundreds of dockers. It also seriously hampered the supply of munitions and other essential equipment to the British Army and forced troops to travel by road.

(Above) Crowd gathers as the hunger strikes at Cork Gaol continue in 1920

While its workers supported both the General Strike and Munitions Strike, the Cork and District Trades and Labour Council also organised a number of local protests. On 22 March 1920, it held a general strike to protest the killing of Lord Mayor Tomás Mac Curtáin. It also organised three stoppages in support of the hunger strike being undertaken by Lord Mayor Terence MacSwiney and other republican prisoners in Cork. Workers from Cork also marched in Mac Curtáin’s and MacSwiney’s funeral processions.

(Above) Funeral of Terence MacSwiney crossing St Patrick's Bridge, 1920.

The Republican Forces

Cork No. 1 Brigade

Irish Republican Army

Cork No. 1 Brigade had its origins in the Cork City Corps of Irish Volunteers that was formed at a public meeting held in Cork City Hall on 14 December 1914. At the end of December 1918, the Brigade was commanded by Tomás Mac Curtáin and covered the entire county. It also had over 8,000 members that were organised into twenty battalions – two in the city and eighteen in the county. Irish Volunteer Headquarters felt this unit was too large and at the beginning of January 1919, three new brigades were formed: Cork No 1, which covered the city and middle of the county; Cork No. 2, which covered North Cork and Cork No. 3, which covered West Cork.

(Above) A Section of an IRA Flying Column 1st Cork Brigade, possibly outside Macroom Castle just before it was burnt down

After the War of Independence commenced, the Irish Volunteers became known as the Irish Republican Army (IRA). During that conflict, Cork No. 1 Brigade would be commanded by Tomás Mac Curtáin (1919-1920), Terence MacSwiney (1920) and Seán O’Hegarty (1920-1921). Other key Brigade staff officers were: Florence O’Donoghue (Adjutant and Intelligence Officer); Joseph O’Connor (Quartermaster); Seán Culhane (Intelligence Officer); Shelia Wallace (Communications Officer) and Fr. Dominic O’Connor (Brigade Chaplain). The home and shop belonging to Shelia Wallace and her sister, Nora, on 13 Brunswick Street, acted as a secret Brigade headquarters until May 1921 when it was closed by the British Army.

(Above) Nora and Sheila Wallace

During the war, the Brigade had ten battalions, two in the city and eight in the county. It also formed a flying column that operated in rural areas and an active service unit that operated within the city. Key engagements included the capture of Carrigtwohill RIC Barracks (3 January 1920), the killing of RIC Divisional Commissioner, Gerald Bryce Ferguson Smyth (17 July 1920), the Dillon’s Cross Ambush (11 December 1920), the Dripsey Ambush (28 January 1921), the Clonmult Ambush (20 February 1921) and the Coolavokig Ambush (25 February 1921). When the Truce came into effect on 11 July 1921, the strength of the Brigade was 7,411 all ranks. [1]

(Above) Reprisal on Dillons Cross after the burning of Cork Dec 1920

Cork No. 2 Brigade

Irish Republican Army

Cork No. 2 Brigade was formed at a meeting held in the home of Batt Walsh at Glashabee, Co. Cork on 6 January 1920. Tomás Mac Curtáin presided at the meeting, and it was part of the reorganisation of the existing Cork Brigade. The Brigade initially consisted of seven battalions and had North Cork as its area of operations. During the War of Independence, it would be commanded by Liam Lynch (1919 – 1921), Seán Moylan (1921) and George Power (1921). Other members of the Brigade staff included Daniel Hegarty and Patrick Clancy (Vice-Commandants); Maurice Twomey and Dan Shinnick (Adjutants); Jeremiah Buckley and Ned Murphy (Quartermasters), Maurice Twomey (Intelligence Officer), Coughlan (Engineer Officer) and Michael Molan (Medical Officer)

(Above) Members of Cork No.2 Brigade Flying Column photographed at a training camp at Liscarroll 1921

During the war, the Brigade formed a flying column which was led by Seán Moylan. Among the Brigade’s key engagements were the attack on British troops at the Wesleyan Chapel in Fermoy (7 September 1919), the capture of Brigadier General Cuthbert Lucas (20 June 1920), the capture of Mallow Military Barracks (28 September 1920), the Tureengarriffe Ambush (28 January 1921), the Mourne Abbey Ambush (15 February 1921), the Clonbannin Ambush (5 March 1921) and the Rathcoole Ambush (16 June 1921).

(Above) General Lucas who was captured by the IRA (pictured with Liam Lynch Sean Moylan Paddy Michael Brennan and Joe Keane June 1920)

By June 1921, Cork No. 2 Brigade was effectively operating as two units. The battalions at the western end of its area of operations were operating under the command of Vice Commandant Paddy O’Brien while those at the eastern end were operating under the command of Commandant George Power. As a result of this, a decision was taken to formally reorganise the unit into two separate brigades. On 10 July 1921, Cork No 4 Brigade, consisting of the Mallow, Kanturk, Charleviile, Newmarket and Millstreet Battalions was formed under the command of Paddy O’Brien. The new Cork No. 2 Brigade now consisted of the Fermoy, Lismore, Castletownroche and Glanworth Battalions under the command of George Power. When the Truce came into effect on 11 July 1921, the strength of Cork No. 2 Brigade was 2,407 and Cork No. 4 Brigade was 3,519 all ranks.

(Above) British forces checkpoint in Fermoy

Cork No. 3 Brigade

Cork No. 2 Brigade was formed at a meeting held at Kilnadur, Dunmanway, Co. Cork on 5 January 1920. Michael Collins presided at the meeting which was part of the reorganisation of the existing Cork Brigade. The brigade consisted of seven battalions and had West Cork as its area of operations. During the War of Independence, it would be commanded by Tom Hales (1919 – 1920), Charlie Hurley (1920 – 1921) and Liam Deasy (1921). Among other officers of the brigade staff were Gibbs Ross and Flor Begley (Adjutant and Assistant Adjutant), Pat Harte, Dick Barrett and Tadhg O’Sullivan (Quartermasters), Frank Neville (Assistant Quartermaster), Seán Buckley (Intelligence Officer), Dan Holland and Dan Sweeney (Transport Officers), Michael Crowley (Engineer Officer) and Con Lucy (Medical Officer).

In the autumn of 1920, the Brigade formed a flying column. Commanded by Tom Barry, this column would become one of the most successful in the IRA and would inflict serious damage on the forces of the Crown operating in West Cork. A veteran of the British Army who fought in Mesopotamia during the First World War, Barry was able to use his military experience to good effect and he proved to be an aggressive and effective commander.

(Above) Photo of members of the 5th Batallion 3rd West Cork Brigade IRA

Among the operations conducted by the Brigade during the war were: Numerous attacks on members of the RIC, the Toureen Ambush (26 October 1920), the Kilmichael Ambush (28 November 1920), the attack on Innishannon RIC Barracks (25 January 1921), the Upton Ambush (15 February 1921), the Crossbarry Ambush (19 March 1921) and the attack on Rosscarbery RIC Barracks (31 March 1921). During the war, the main British Army unit opposing the Brigade in West Cork was the 1st Battalion of the Essex Regiment, which was based in Kinsale and Bandon. When the Truce came into effect on 11 July 1921, the strength of Cork No. 3 Brigade was 5,653 in all ranks.

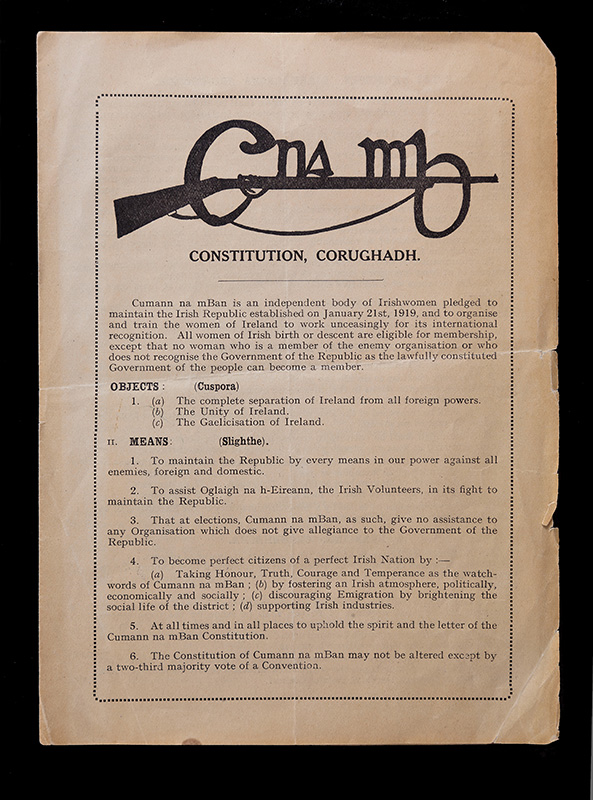

Cumann na mBan

The first branch of Cumann na mBan (Irishwomen's Council) was formed at a meeting held in Wynn’s Hotel in Dublin on 2 April 1914. The meeting was chaired by Professor Agnes Farrelly of University College Dublin. Though nominally independent, the organisation acted as a female auxiliary to the Irish Volunteers. According to its constitution, its primary aims were to advance the cause of Irish liberty and to assist in arming and equipping a body of Irish men for the defence of Ireland.

(Above) Copy of the Cumann Na mBan constitution

(Above) Dr Helene O'Keeffe from UCC gives us an overview of Cumann Na mBan activities during the Irish War of Indpendence

Within weeks of the inaugural meeting, other branches were formed throughout Ireland. In May 1914 a meeting was held in the home of Mary MacSwiney in Blackrock in Cork to discuss the formation of a branch in the city. A public meeting to establish this branch was held in a hall known as An Dún, on Queen Street. The first officers elected were: Madeline O’Leary President; Mary MacSwiney, Vice-President; Miss Nora O'Brien, Secretary and Madge Barry, Treasurer. Members were trained by officers of the Irish Volunteers who conducted classes in arms drill, foot drill, first aid and Morse code. They also received weapons training.

(Above) This Cumann Na mBan tunic belonged to Rita O’Beirne (nee Mintern) who was a member of the Cumann na mBan in Cork during the War of Independence

(Above) Group of Cumann na mBan volunteers

When the War of Independence commenced, Cumman na mBan had branches throughout Cork city and county that were organised into District Councils. There were fifteen branches affiliated to the Cork District Council which covered the city and parts of mid- Cork. During the war, members of the organisation provided administrative, communication and logistical support to the IRA. Among the tasks carried out by its members were: gathering intelligence, carrying dispatches, providing ‘safe houses’, storing and conveying arms and ammunition, organising funerals and providing support for republican prisoners. Members also raised funds and actively supported Sinn Féin candidates during election campaigns. The sacrifices and efforts made by members of the Cumman na mBan in Cork to the Republican side during the war, on both the political and military fronts, cannot be underestimated and contributed significantly to the fight for Irish freedom.

(Above) Group of Cumann na mBan outside the front of the Beamish and Crawford brewery

Republican Forces-Biographies

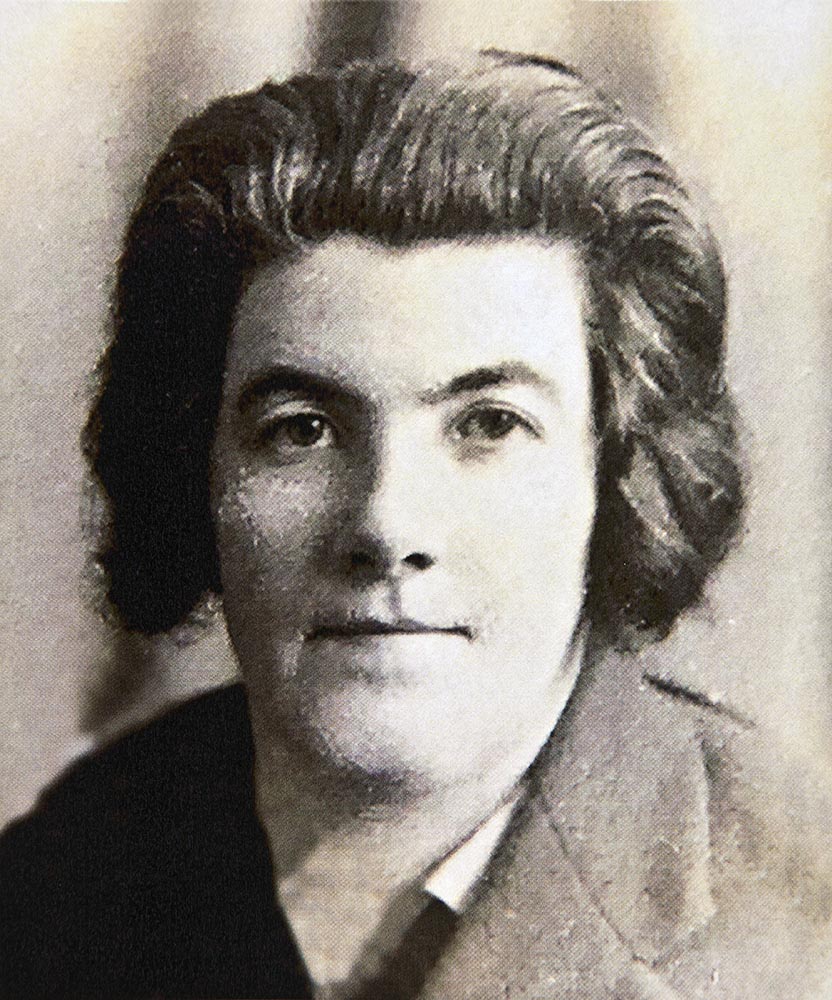

Sheila and Nora Wallace

Shelia and Nora Wallace

Headquarters, Cork No. 1 Brigade, IRA

Shelia (b.1887) and Nora (b.1893) were two of the ten children of Jeremiah and Mary Wallace (née Keeffe) of Kilcullen South, Donoughmore, Co. Cork. In 1910, the sisters moved to Cork and they later opened a newsagent and shop in the centre of the city at 13 Brunswick Street (now Saint Augustine Street). Devout Catholics and cultural nationalists, they were also socialists and supporters of James Larkin, James Connolly and Countess Markievicz. Their shop also sold political pamphlets and periodicals that promoted the Irish language.

(Above) Nora Wallace

The sisters became involved in the Irish Citizen Army and, in 1917, they established an organisation known as the Women’s Citizen Army in Cork. Their belief in an independent Ireland also led them to support the republican movement. In 1918, their shop became a meeting place for Cork republicans, and it soon developed into the de facto headquarters of Cork No. 1 Brigade of the IRA. Both sisters also joined the IRA and Shelia was appointed a Staff Officer in charge of communications.

(Above) The Wallace sisters shop on St Augustine St, Cork.

(Above) Sheila Wallace

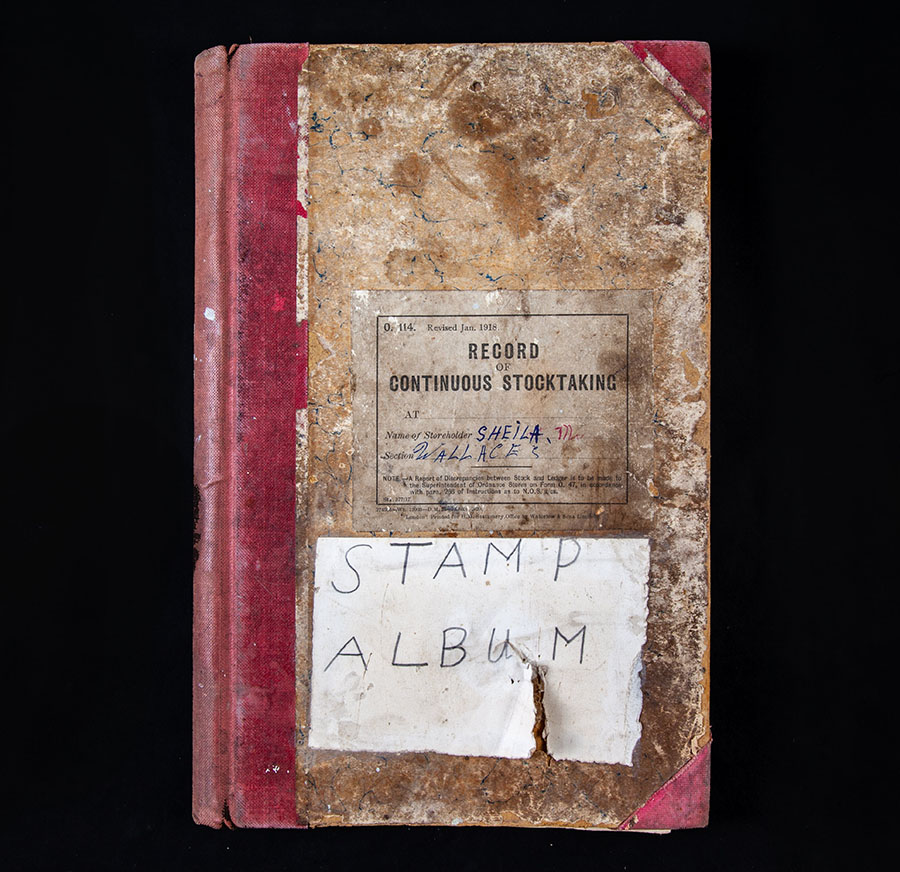

During the War of Independence, the sisters processed IRA despatches and intelligence reports, stored and distributed arms and ammunition and deciphered codes. On the night of 19 March 1920, Tomás Mac Curtáin attended a meeting in their shop a few hours before he was killed. The sisters eventually came under suspicion from British authorities. Their shop was closed by the British Army in May 1921, and they were ordered to leave the city. They both took the republican side during the Civil War. Shelia passed away on 14 April 1944. Nora continued working in the shop until 1960. She died on 17 September 1970. Both sisters were buried in St. Finbarr’s Cemetery.

(Above) A ledger used by the Wallace Sisters to record an inventory of arms for Cork No. 1 Brigade.

For more see our Resources Page

(Courtesy of Bill Murphy)

Tom Hales

Commandant Tom Hales

Cork No. 3 Brigade, IRA

Thomas (Tom) Hales was born on 5 March 1892 at Knocknacurra House, Ballinadee, Bandon, Co. Cork. The son of Robert and Mary Hales (née Fitzgerald), he was educated at Ballinadee National School and Warner’s Lane School in Bandon. At an early age, he developed a hatred of British rule, as did his brothers Seán, William, Robert and Donal. This led him to join the Irish Volunteers when that organisation was established in November 1913. He became captain of the Ballinadee Company and he paraded with that unit on Easter Sunday 1916 in accordance with the original plans for the Rising.

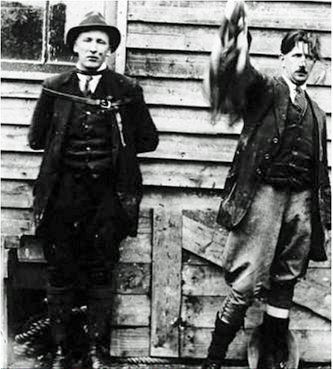

Hales evaded arrest in the aftermath of the Easter Rising and he later became commander of the Bandon Battalion of Irish Volunteers. In January 1919, he was appointed the first commanding officer of Cork No. 3 Brigade. Under his leadership, the brigade conducted several operations against Crown forces. On 27 July 1920, Hales and the brigade quartermaster, Patrick Harte, were arrested by Crown forces at Laragh, Bandon. Both men were tortured while in custody. Hale’s mouth and hands were badly damaged and he had to spend time in hospital before being tried and sentenced to two years penal servitude. He served his sentence in Dartmoor and Pentonville prisons and was only released at Christmas 1921.

(Above) Patrick Harte and Tom Hales being tortured while in custody 1920.

During the Civil War, Hales commanded Cork No. 3 Brigade of the Anti-Treaty IRA. Arrested in November 1922, he was detained in Cork Prison and Hare Park Camp until Christmas 1924. On 30 April 1927, he married Ann Lehane and the couple had five children. Tom Hales died 29 April 1966 at St Finbarr's hospital, Cork, and is buried at St Patrick's Cemetery, Bandon.

Mary Bowles

The story of Mary Bowles

(Above) Historian Anne Twomey gives us a insight into Cumann Na mBan member Mary Bowles

Sean O'Hegarty

Commandant Seán O’Hegarty

Officer Commanding, Cork No. 1 Brigade, IRA

Seán O'Hegarty, was born at 26 Evergreen Street, Cork, on 21 March 1881, the son of John and Katherine Hegarty (née Hallahan). Educated at the North Monastery School, he subsequently obtained employment in the post office and became involved in a number of nationalist organisations including the Gaelic League, Sinn Féin and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). In 1912, he married Cumann na mBan activist, Maghdalen (Mid) Ní Laoghaire. The following year, he joined the Cork City Corps of Irish Volunteers and was appointed to the unit’s executive.

Sean O'Hegarty's Austrian Steyr gun.

In October 1914, O'Hegarty was dismissed from the post office and was excluded from Co. Cork by the British authorities. He moved to Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, but returned to Ballingeary, Co. Cork, prior to the 1916 Easter Rising. In 1917, he became second-in-command of the Cork Brigade of Irish Volunteers. By now, he was also the senior IRB officer in Cork. When this exposed the existence of a dual IRB/Volunteer chain of command in the Brigade, he stepped down and returned to the ranks as a Volunteer.

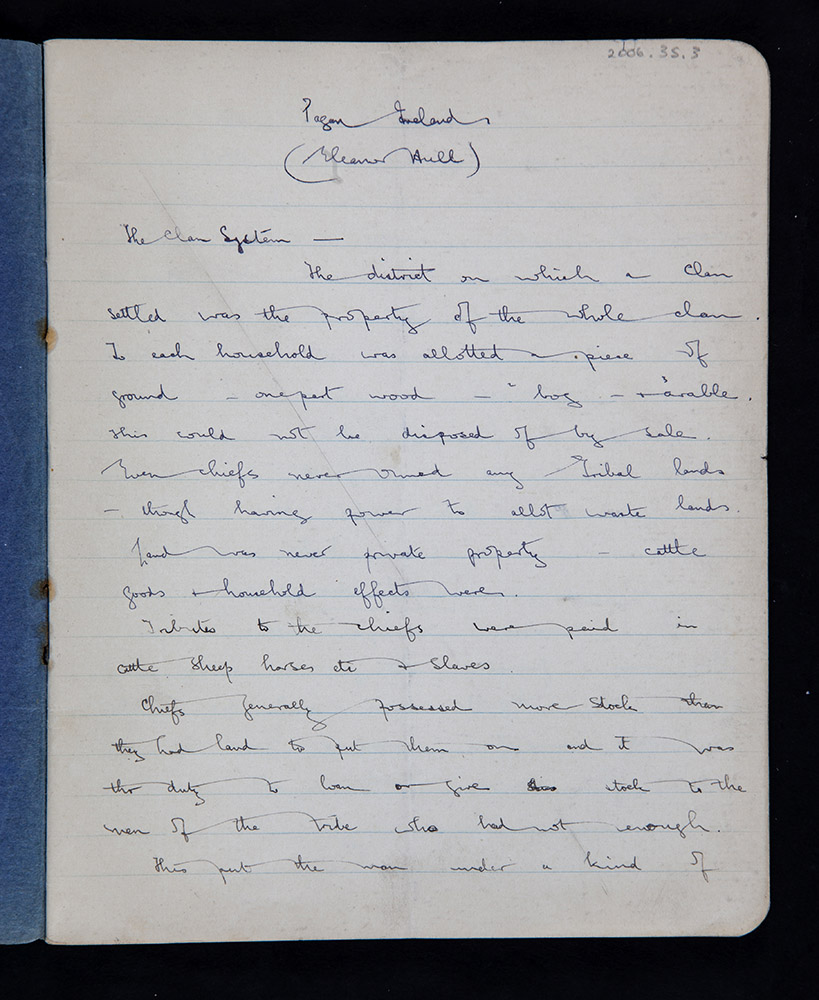

(Above) Sample page from one of O'Hegarty's notebooks. For more info see our Resources Page

After Terence MacSwiney died on hunger strike on 25 October 1920, O’Hegarty became commander of Cork. No. 1 Brigade of the IRA. Puritanical in nature, he was also an aggressive and effective leader, personally taking part in a number of operations including the attempt to capture Major General Strickland (24 September 1920) and the Coolavokig Ambush (25 February 1921). He also authorised the execution of a number of suspected spies and informers. He resigned from the IRA after the Civil War broke out in June 1922 and remained neutral during the conflict. He died on 31 May 1963 and was buried in Kilmurry Cemetery.

Liam Lynch

Commandant Liam Lynch

Officer Commanding Cork No. 2 Brigade IRA

Liam Lynch was born on 9 November 1893 in Barnagurraha, Anglesboro, Co. Limerick. He was the fifth of seven children born to farmer, Jeremiah, and his wife, Mary (neé Kelly). In 1910, after attending Anglesboro National School, he moved to Mitchelstown, Co. Cork, to take up a three-year apprenticeship in a hardware store. Five years later he moved to Fermoy, where he worked in the store of Messrs J. Barry & Sons.

(Above) The body of General Liam Lynch lying in state, Clonmel 1923.

While in Mitchelstown, Lynch became a member of the Gaelic League and the Irish Volunteers. When the Volunteer movement split in September 1914, over the issue of participating in the First World War, Lynch initially remained with the National Volunteers. However, when he saw Thomas and William Kent being marched across the bridge in Fermoy on 2 May 1916, he decided to join the Fermoy Company of Irish Volunteers. In January 1919, he was appointed the Commanding Officer of the newly formed Cork No. 2 Brigade.

(Above) Liam Lynch's binoculars.

During the War of Independence, Lynch proved to be a talented and aggressive commander. Among the operations he led were the ambush of British soldiers in Fermoy (7 September 1919); the capture of Brigadier General Cuthbert Lucas (26 June 1920) and the capture of the military barracks in Mallow (28 September 1920). In April 1921, Lynch was appointed the Commanding Officer of the 1st Southern Division which comprised of units from counties Cork, Kerry, Waterford and west Limerick. He opposed the Treaty and, during the Civil War, he became Chief of Staff of the Anti-Treaty IRA. On 10 April 1923, he was shot and mortally wounded in the Knockmealdown Mountains while trying to avoid a National Army patrol. He was buried in Kilcrumper Cemetery, Co. Cork.

Flor O'Donoghue

Captain Florence O’Donoghue

Headquarters, Cork No. 1 Brigade, IRA

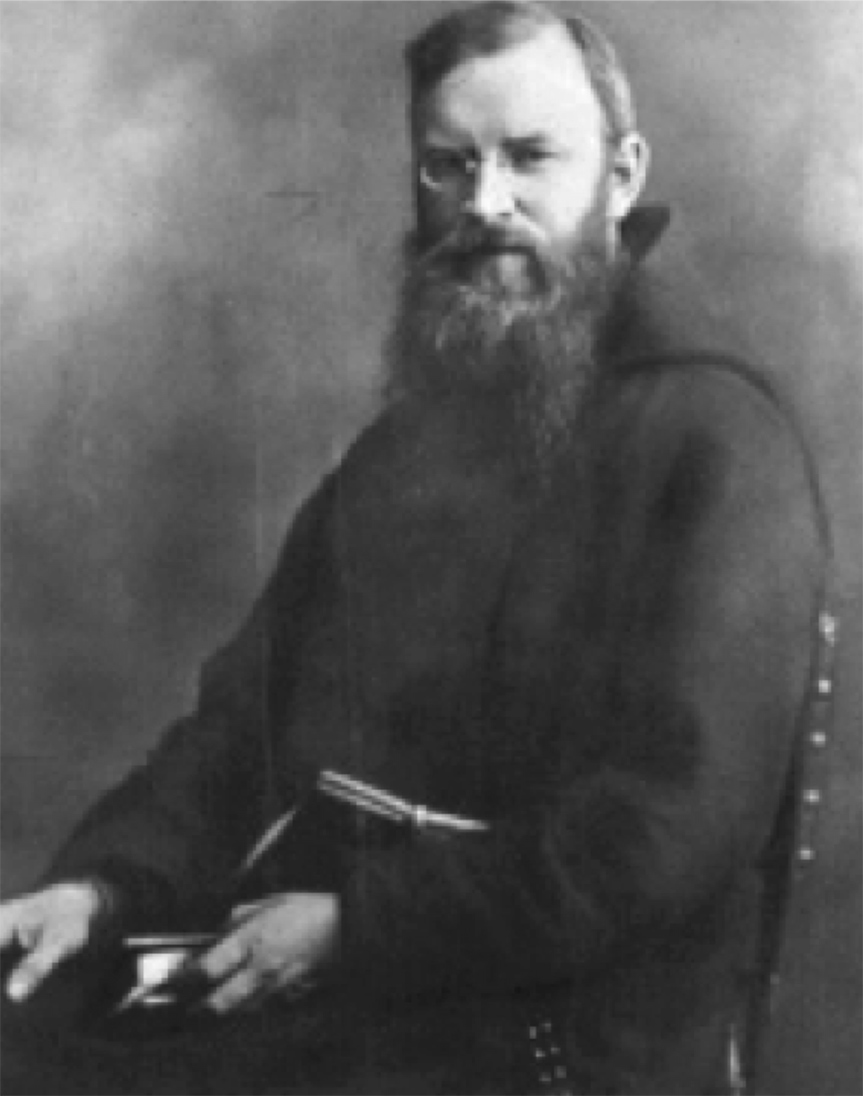

Florence ‘Florrie’ O'Donoghue was born on 6 May 1897, in Rathmore, Co. Kerry; the son of Timothy and Julia O'Donoghue (née Murphy). Educated locally, he moved to Cork City in 1910 to work in a shop owned by his mother's cousin, Michael Nolan, at 55 North Main Street. In 1917, he joined the Cork Brigade of Irish Volunteers and was sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). The following year, he was appointed Brigade Adjutant and Intelligence Officer. He went on to establish an effective intelligence network that would contribute to many successful operations conducted by the IRA.

In 1919, O’Donoghue embarked on a romantic relationship with Josephine Marchment, a war widow employed in Victoria Barracks. She had had two young sons, Gerald, who lived with her in Cork, and Reggie, who lived with her in-laws in Wales. In November 1920, O’Donoghue and other members of the IRA abducted Reggie and took him to Cork to be reunited with his mother. In turn, Josephine agreed to provide O’Donoghue with military intelligence from the Barracks. The couple were married on 27 April 1921 and would have four children of their own.

(Above) Florence O'Donoghue in later years.

In 1921, O’Donoghue was appointed Adjutant and Intelligence Officer of the 1st Southern Division, IRA. He also became the Cork County Centre of the IRB. After the Civil War broke out in June 1922, he formed the Neutral IRA Association with Seán O’Hegarty. During the Emergency, O’Donoghue joined the Defence Forces and worked in military intelligence. In later years, he became a noted historian and secretary of a number of Cork-based associations. He passed away on 16 December 1967 and was buried in St. Finbarr’s Cemetery.

Father Dominic

Father Dominic O’Connor O.F.M. Cap

Chaplain, Cork No. 1 Brigade

John Francis O’Connor was born into a devout Roman Catholic family in Cork on 13 February 1883, the son of John and Mary O’Connor (née Sheehan). He entered the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin (O.F.M. Capuchin) in October 1899, and received the religious name of Dominic. On 17 March 1906, he was ordained a priest at the Capuchin Friary in Kilkenny.

(Above) Father Dominic (centre with beard) visiting Terence MacSwiney in Brixton Prison 1920

In April 1916, Fr. Dominic volunteered to serve as a chaplain with the British armed forces and went on to serve in Salonika. He relinquished this post in July 1917, and returned to Cork. His support for an Irish Republic led Tomás Mac Curtáin to appoint him Chaplain to Cork No. 1 Brigade of the IRA and to the Lord Mayor of Cork. His brother, Joseph O’ Connor, was Quartermaster of the Cork No. 1 Brigade.

(Above) Father Dominic's body being repatriated back to Ireland in 1958

Fr. Dominic was among the first to arrive at Mac Curtáin’s home after he was killed there on 20 March 1920. He also administered to Lord Mayor, Terence MacSwiney, during his hunger strike in Brixton Prison, London. When Bishop Cohalan of Cork threatened to excommunicate members of the IRA in December 1920, Fr. Dominic assured Volunteers that the acts of the IRA were ‘not sinful’. Later that month, he was arrested in Dublin and sentenced to three years in Pankhurst Prison. Released in January 1922, the following month he was granted the Freedom of Cork for ‘his valuable services rendered to the first two Republican Lord Mayors of Cork’. In November 1922, he was transferred to the Capuchin Mission in Oregon in the United States. He died there on 17 October 1935. His remains were repatriated to Ireland in June, 1958, and buried in the Capuchin College in Rochestown, Co. Cork.

The Crown Forces

Royal Irish Constabulary

When the War of Independence commenced in January 1919, an armed police force known as the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) was responsible for policing all of Ireland with the exception of Dublin city, which was policed by the unarmed Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP). The RIC had its origins in the Peace Preservation Force established by Sir Robert Peel, the Chief Secretary for Ireland in 1814. In 1836, a single force known as the Irish Constabulary was established. As a reward for its part in suppressing the Fenian Rising of 1867, Queen Victoria granted this force the right to use the prefix ‘Royal’.

(Above) Royal Irish Constabulary helmet and storage box

The RIC recruited in Ireland and, in January 1919, its strength was about 9,500. There were also some 1,300 RIC barracks in the country. Cork city was organised into a North and South District, each under the control of a District Inspector. The headquarters of the city and the South District was in Union Quay Barracks. Other barracks in this district were: the Bridewell, Blackrock, Blackrock Road, College Road, Togher, Tuckey Street and Victoria Cross. The headquarters of the North District was in King Street Barracks. Other barracks in this district were: Blackpool, Carrignavar, Commons Road, Lower Glanmire Road, Kilbarry, St. Luke’s, Shandon Street and Sunday’s Well. Barracks were also located in every town in the county. During the war, many of these barracks were attacked and destroyed by the IRA.

On 10 April 1919, Dáil Éireann passed a motion calling on people to socially ostracise the RIC. Early in the war, the IRA also adopted a strategy of targeting individual constables. These actions led to hundreds of resignations from the force and, in 1920, it was reinforced by personnel recruited in Britain who became known as the ‘Black and Tans’ and also by the Auxiliary Division of the RIC, which was comprised of ex-British military officers. In August 1922, the RIC was disbanded. It was replaced by the Garda Síochána in the Irish Free State and the Royal Ulster Constabulary in Northern Ireland.

(Above) Royal Irish Constabulary baton

British Army

The British Army was the largest and best equipped opponent faced by the IRA during the War of Independence. There were approximately 55,800 British soldiers located in Ireland during the conflict. These troops were based at a number of military barracks and posts situated throughout the country and were organised into units based on geographical areas of operation. The principal British formations in Ireland at that time were the 5th Division, the 6th Division, the Dublin District and the Ulster Brigade. Each of these formations contained a number of smaller units such as infantry, artillery and cavalry brigades and engineer, transport and signal companies. They also contained units from the ordnance, medical, and military police corps.

(Above) Civilians being rounded up by British forces in Macroom to fill in a road that was destroyed by the IRA in 1921

During the War of Independence, Victoria Barracks in Cork held the headquarters of the 6th Division. This unit had the province of Munster and the counties of Kilkenny and Wexford as its area of operations. It contained three infantry brigades, the 16th, 17th and 18th. The 17th Brigade was responsible for operations in Co. Cork. In addition to Victoria Barracks in Cork city, there were British Army garrisons in Ballincollig, Fermoy, Bantry, Kanturk, Kinsale, Bandon, Mallow, Kilworth, Buttevant, Ballyvonare, Moore Park and in forts Camden, Carlisle, Templebreedy and Westmoreland.

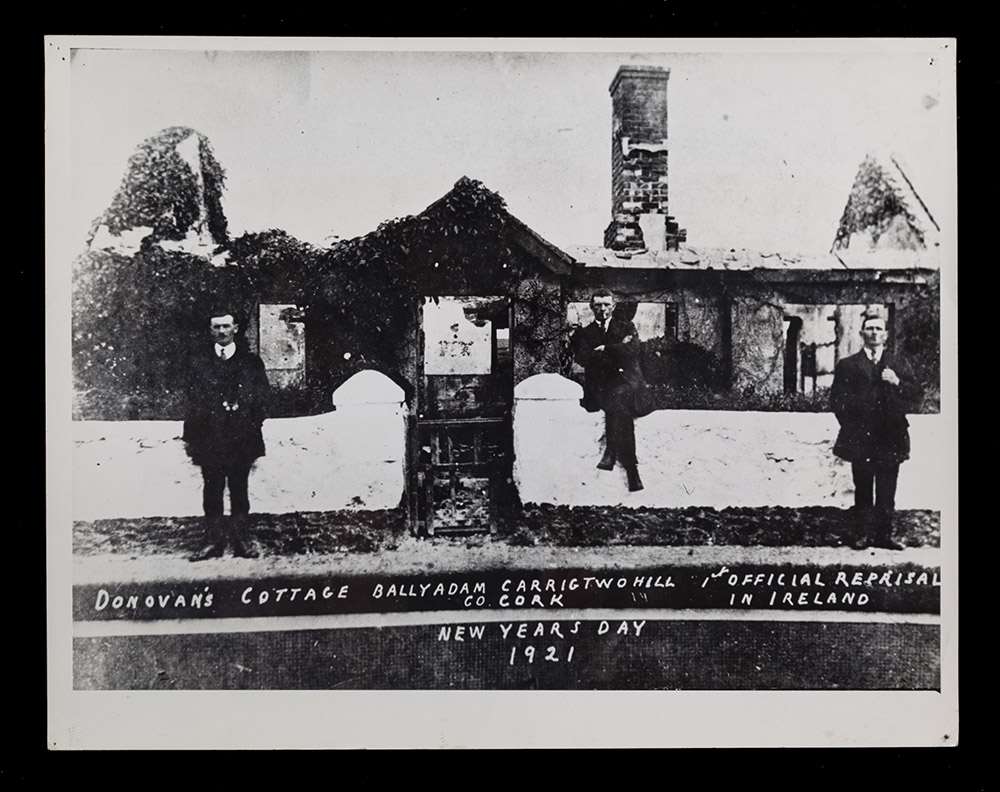

When the war commenced, the army acted primarily in support of the police. However, as the conflict continued, its powers would increase. In August 1920, the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act gave the military court-martial jurisdiction over all crimes committed in the country. On 10 December 1920, Martial Law was proclaimed in counties Cork, Kerry, Limerick, and Tipperary and from January 1921, the British Army was empowered to carry out ‘official’ reprisals. During the conflict, it mounted several successful operations against the IRA in Co. Cork, most notably at Dripsey, Upton, Clonmult, and Mourne Abbey. Despite this, and its superior firepower, equipment and mobility, by the time the Truce came into effect on 11 July 1921, the British Army had failed to defeat the IRA.

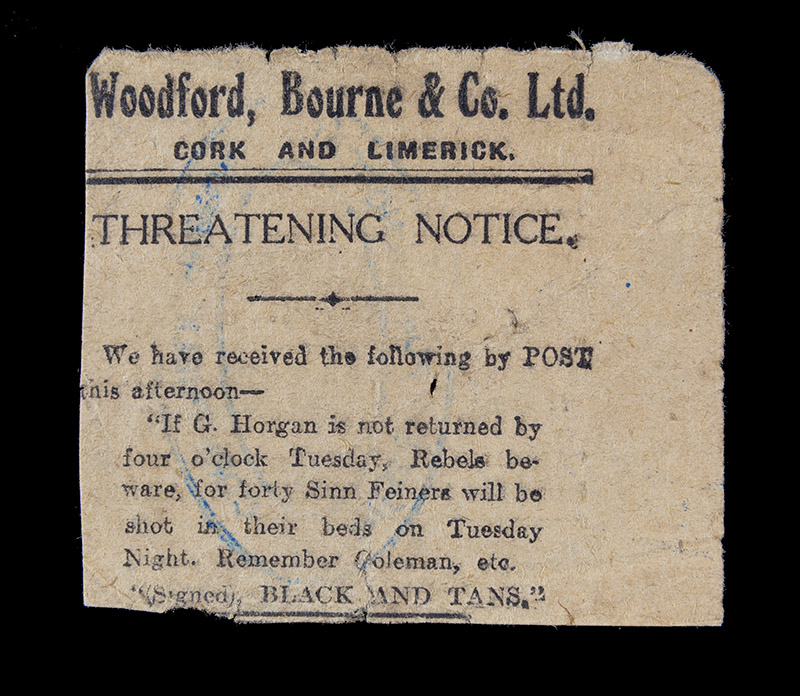

Black and Tans

The decision taken by Dáil Éireann on 10 April 1919, calling on the Irish people to socially ostracise members of the RIC and the numerous IRA attacks led to hundreds of resignations and retirements from the force. There was also a fall in the number of new recruits in Ireland. This shortage in manpower led police authorities to abandon many rural RIC barracks. In an effort to deal with this situation, the British government decided to recruit members for the RIC in Britain. On 27 December 1919, T. J. Long, the Inspector General of the RIC, gave the necessary authorisation and the first British recruits, officially known as the RIC Special Reserve, joined the following month.

In February 1920, the new recruits started arriving in Ireland. Because of a clothing shortage, they were clad in a mixture of khaki British Army and dark green RIC uniforms. This earned them the nickname ‘Black and Tans’ after the Kerry Beagles of the Scarteen Hunt. Initially trained in Hare Park Camp in the Curragh, Co. Kildare, and later at Gormanstown Camp, Co. Meath, the Black and Tans were deployed to barracks throughout the country. Comprised of ex-servicemen who received rudimentary police training, they quickly proved ineffective and gained a reputation for ill-discipline, drunkenness and casual violence. The first Black and Tans arrived in Cork city in March 1920 and some, such as Constable Stephen Chance, who was based in Shandon Street RIC Barracks, became particularly notorious for their cruelty and the way they terrorized the civilian population.

(Above) Newspaper clipping from the Black and Tans warning of reprisals

In all, almost 11,000 individuals, around 890 of whom were Irish born, joined the Black and Tans. In addition to the RIC Special Reserve, this number includes temporary constables and members of the Veterans and Drivers Division. After the RIC was disbanded in August 1922, many Black and Tans became unemployed while others joined the Royal Ulster Constabulary and the Palestine Police Force.

Auxiliary Division, Royal Irish Constabulary

On 11 May 1920, the British government met to consider the situation in Ireland. Despite the recent deployment of the Black and Tans, IRA operations were on the increase. At the meeting, Winston Churchill, the Secretary of State for War, suggested the establishment of a ‘Special Emergency Gendarmerie, which would become a branch of the Royal Irish Constabulary’. Although his suggestion was rejected by a committee chaired by General Macready, the commander of British Forces in Ireland, it was revived the following July by Major-General Tudor, the Police Adviser to the Dublin Castle Administration.

(Above) Balmoral type cap/hat from the Auxiliary Police

Known as the Auxiliary Division of the RIC (ADRIC), and commanded by Brigadier-General Frank Crozier, the force would consist of former military officers recruited in Britain. Successful applicants would be paid £7 per week and given the rank of ‘temporary cadet’ but those selected to be Auxiliary officers were given the same rank as their RIC counterparts. Recruiting commenced in July 1920, and on completion of a six-week police course, the Auxiliaries were assigned to alphabetically designated companies located in areas with high levels of IRA activity. Dressed in a RIC uniform or their old army uniforms with appropriate police badges, all Auxiliaries wore a distinctive Tam O’ Shanter cap. Though nominally under the command of the RIC, many Auxiliary companies acted independently and the force soon gained a reputation for drunkenness, ill-discipline, and brutality worse than that of the Black and Tans.

(Above) Group of Black and Tans and Auxiliaries near Union Quay RIC barracks, Cork

Five Auxiliary companies were deployed in Co. Cork during the War of Independence: J Company in Glengarriff and Macroom; K Company in Cork city and Dunmanway; L Company in Millstreet and O Company in Dunmanway. K Company, which was under the command of former Royal Air Force Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Owen Latimer, and based in Victoria Barracks, was responsible for the arson attack known as the Burning of Cork (11/12 December 1920). In all, around 2,200 men served in the ADRIC. The force was disbanded along with the rest of the RIC in August 1922.

Crown Forces-Biographies

Geoffrey Lee Compton-Smith

Major Geoffrey Lee Compton-Smith

2nd Battalion, Royal Welch Fusiliers

Geoffrey Lee Compton-Smith was born on 19 August 1889 in South Kensington, London, the son of William and Henrietta Compton-Smith. A graduate of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, he was commissioned into the Yorkshire Regiment but in June 1915 he transferred to the Royal Welch Fusiliers. During the First World War, he commanded the 10th Battalion of that regiment and was wounded. He was also Mentioned in Despatches and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and the French Légion d'honneur. In 1916, he married Gladys Lloyd and the couple had one child, a daughter, Anne.

(Above) British military bayonet c.1920.

After the war, Major Compton-Smith was appointed camp commandant of Ballyvonare Camp near Buttevant, Co. Cork. On 16 April 1921, he was captured outside Blarney by an IRA unit led by Frank Busteed. Four IRA Volunteers were due to be executed in the Military Detention Barracks in Cork on 28 April and the IRA decided to hold Compton-Smith hostage in an effort to prevent their death. The British military authorities in Cork were informed that if the Volunteers were shot, then Compton-Smith would be executed.

(Above) British army compass, c.1920.

Compton-Smith was detained in a number of houses in Donoughmore. When the Volunteers were shot on 28 April, he was executed two days later. His remains were initially buried in Barrahaurin bog. However, in 1926, they were exhumed and reburied in the British military cemetery outside Fort Carlisle, Co. Cork. During his captivity, Compton Smith developed a good relationship with his captors and he spoke well of them in the last letters he wrote before his death. He is believed to have been the inspiration for the short story,Guests of the Nation, written by the Cork author Frank O’Connor.

Oswald Ross Swanzy

District Inspector Oswald Ross Swanzy

Royal Irish Constabulary

The son of solicitor James and Elizabeth Swanzy (née Ross), Oswald Ross Swanzy was born in Castleblaney, Co. Monaghan, on 15 July 1881. He joined the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) as a cadet on 28 February 1905. On completion of his training at the RIC Deport in the Phoenix Park in Dublin, he was promoted 3rd Class District Inspector. He went on to serve at Rathkeale, Co. Limerick, and at Carlow.

In January 1916, Swanzy was appointed RIC District Inspector for Cork City North and was based in the RIC Barracks on King Street. He was soon involved in a number of investigations and arrests of republican suspects. The IRA also believed that he played a major part in the killing of Lord Mayor Tomás Mac Curtáin who was shot dead at his home at 40 Thomas Davis Street in Blackpool in the early hours of 20 March 1920.

(Above) `Alleged Lugar used in the execution of Swanzy.

Following the death of Mac Curtáin, the RIC transferred Swanzy to Lisburn. However, Seán Culhane, an IRA intelligence officer with Cork No. 1 Brigade learned of his location when he found a hat box with his name on it at the Glanmire Road railway station. When it received this information, IRA Headquarters in Dublin decided to execute Swanzy and members of Cork No. 1 Brigade were authorised to carry out the operation. On 22 August 1920, an IRA squad which included Seán Culhane and Dick Murphy from Cork and Roger McCorley from the Belfast Brigade shot Swanzy dead as he was coming from Christchurch Cathedral in Lisburn. After he was killed, serious sectarian rioting erupted in Lisburn and a number of Catholic homes and businesses were destroyed.

Gerald Bryce Ferguson Smyth

Lieutenant Colonel Gerald Bryce Ferguson Smyth

Royal Irish Constabulary

Gerald Bryce Ferguson Smyth was born on 7 September 1885, in Dalhousie, India, He was the son of George and Helen Smyth (née Ferguson). In 1905, he was commissioned into the Royal Engineers. During the First World War, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and Bar, the French Croix de Guerre and the Belgian Croix de Guerre. He was also wounded six times, losing his left arm in October 1914. In December 1916, he took command of a battalion of King's Own Scottish Borderers which was part of the 9th (Scottish) Division commanded by Brigadier General Henry Hugh Tudor. He ended the war as a Brevet Lieutenant General in command of the 93rd Infantry Brigade.

In May 1920, General Tudor, now police adviser to the civil administration in Ireland, recommended Smyth for the position of RIC divisional commissioner for Munster. After taking up that appointment, Smyth issued a series of radical counter-insurgency instructions designed to suppress the IRA campaign in the province. On 19 June 1920, he arrived at the RIC Barracks at Listowel, Co. Kerry, accompanied by Tudor. While there, he gave an inflammatory speech that infuriated some members of the garrison and led to the incident known as the ‘Listowel Mutiny’.

(Above) Possible funeral of Ferguson-Smyth at Victoria Barracks (now Collins Barracks).

The IRA now considered Smyth to be a major threat and a decision was taken to eliminate him. On the night of 17 July 1920, an IRA unit led by Dan ‘Sandow’ O’Donovan, entered the County Club on the South Mall in Cork and shot him dead. The killing of Smyth led to clashes between civilians and Crown forces in Cork, the expulsion of Catholics from Belfast shipyards and a series of sectarian attacks in Banbridge, Co. Down.

(Above) Royal Irish Constabulary station/barracks external plaque

Arthur Percival

Major Arthur Percival

1st Battalion, Essex Regiment

Arthur Ernest Percival was born on 26 December 1887 at Aspenden Lodge in Hertfordshire, England, the second son of Alfred Reginald and Edith Percival (née Miller). Educated at Rugby, he joined the Officer Training Corps of the Inns of Court on the outbreak of the First World War and he was promoted 2nd Lieutenant after five weeks training.

In 1915, Percival deployed to France with the 7th (Service) Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment. In September 1916, he was badly wounded leading at attack on the Schawben Redoubt and the following month, he transferred to the Essex Regiment. During the war, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order, the Military Cross and the French Croix de guerre.

(Above) The opening of the Cork Assizes (higher criminal court), now the Washington Street courthouse 1920.

In 1920, Percival was sent to West Cork to join the 1st Battalion of the Essex Regiment as a company commander. However, he later became the battalion intelligence officer. Tom Barry, the commander of the Flying Column of Cork No. 3 Brigade of the IRA, stated that Percival was ‘easily the most vicious anti-Irish of all serving British officers’. In the summer of 1920, Percival captured Tom Hales, commander of Cork No. 3 Brigade and Patrick Harte, the brigade quartermaster. Both men were badly tortured during their interrogation. Harte never recovered from this ordeal and died in 1925. Percival was appointed to the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for their capture. Though targeted by the IRA, he survived the War of Independence unscathed. During the Second World War, Percival was appointed General Officer Commanding Malaya and became known as the officer who surrendered Singapore to the Japanese Army on 15 February 1942. He died in King Edward VII's Hospital for Officers in London on 31 January 1966.

Bernard Law Montgomery

Major Bernard Law Montgomery

Brigade Major, 17th Infantry Brigade

Born in Kennington, Surrey, on 17 November 1887, Bernard Law Montgomery was the son of Henry and Maud Montgomery (née Farrar). His father was an Anglican vicar and in 1889 he was appointed Bishop of Tasmania. After the family returned to London in 1901, Montgomery attended St. Paul’s School before entering the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst. In 1908, he was commissioned into the 1st Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment as a 2nd lieutenant. During the First World War, Montgomery served on the Western Front with that regiment and held a number of staff appointments. He was also shot in the lung by a sniper and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for leadership under fire.

(Above) In the village of Meelin Co. Cork on the 6th January 1921, the male population is rounded up for questioning by British forces

In January 1921, after graduating from Staff College, Montgomery was sent to Victoria Barracks in Cork to take up the position of brigade major with the 17th Infantry Brigade. The previous November, his cousin, Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Montgomery, was killed by the IRA in Dublin. As a brigade major, Montgomery was responsible for planning the unit’s counter-insurgency operations. He would remain in Victoria Barracks until it was evacuated by the British Army on 18 May 1922. During his time in Cork, he produced a comprehensive set of operational orders that were designed to improve the efficiency of the British Army campaign against the IRA.

In the Second World War, Montgomery rose to the rank of field marshal. He also became famous as the man who defeated Field Marshal Rommel at the Battle of El Alamain in 1942 and he commanded the Allied landings at Normandy in 1944. Bernard Law Montgomery died on 24 March 1976 and is buried in Holy Cross churchyard, in Binsted, Hampshire, England.

Edward Peter Stickland

Major General Sir Edward Peter Strickland

6th Division, British Army

Edward Peter Strickland was born on 3 August 1869 at Snitterfield, Warwickshire, England, the son of Frederick and Frances Strickland. In 1888, he was commissioned into the Norfolk Regiment and went on to serve in Upper Burma (1888-89) and with the Egyptian Army (1889-1905). He also served in India and Nigeria. During the First World War he served on the Western Front as commander of the 1st Battalion, Manchester Regiment, the Jullundur Brigade, the 98th Brigade and the 1st Division. He led that division during the battles of the Somme and Passchendaele, the 1918 German Spring Offensive and the final British offensive known as the ‘Hundred Days’

After the end of the war, Strickland became commander of the Western Division of the British Army of the Rhine. In 1919, he was appointed General Officer Commanding (GOC) the 6th Division in Ireland. This unit had the province of Munster together with the counties of Kilkenny and Wexford as its area of operations and its headquarters was located in Victoria Barracks in Cork.

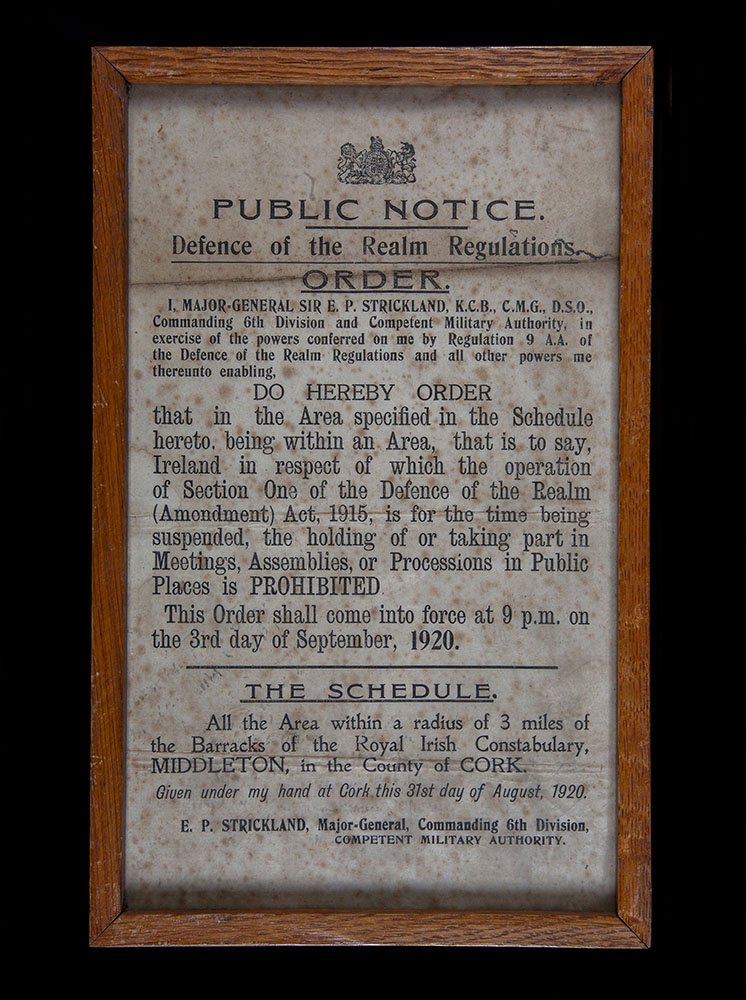

(Above) Notice Prohibiting Public Meetings signed by General Strickland for Middleton 1920.

On 24 September 1920, the IRA attacked Strickland’s staff car at the bottom of St. Patrick’s Hill in Cork in an unsuccessful attempt to capture him and hold him hostage to secure the release of Lord Mayor Terence MacSwiney who was then on hunger strike in Brixton Prison. Strickland became the Military Governor of counties Cork, Kerry, Limerick and Tipperary when the British Government declared Martial Law in those counties on 10 December 1920. He remained in command of the 6th Division until it withdrew from Ireland in 1922. Strickland retired from the army in 1931. He died at his home at Snettisham, Norfolk, on 24 June 1951.

Guerrilla Warfare

(Above) Explosive device. One of 60 devices found during a building renovation on Popes Quay in 2003. Dated back to the War of Independence

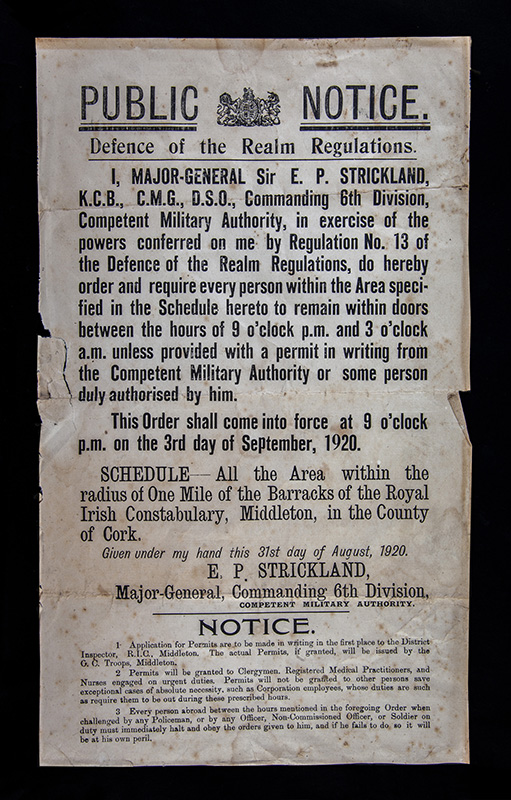

(Above) Curfew notice for the Middleton area of Cork, signed by General Strickland 1920

The War of Independence can be divided into three phases. In the first (January 1919 – March 1920), the IRA carried out isolated attacks on members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP). The second phase (March – December 1920) saw an intensification of IRA attacks and the formation of IRA flying columns and active service units. In response, the British government deployed the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries and introduced Martial Law in the south of the country. Crown forces also commenced a policy of unofficial reprisals, the largest of which was the Burning of Cork. The third phase of the conflict (January – July 1921) saw an increase in operations conducted by the British Army and a change in the tactics it employed against the IRA. It also saw the start of the negotiations that ultimately led to the Truce of 11 July 1921.

(Above) Three Donovan brothers outside their burnt down house at Ballyadam near Carrigtwohill New Years Day 1921

IRA units in Cork city and county contained some of the most successful guerrilla fighters of the war. Among these were men such as Tom Barry, Liam Lynch, Mick Murphy and Dan ‘Sandow’ O’Donovan. Cork IRA units also conducted some of the most successful IRA operations such as the capture of Carrigtwohill RIC Barracks (3 January 1920), the capture of Mallow Military Barracks (28 September 1920) and the Kilmichael Ambush (28 November 1920).

Politics & Propaganda

Politics and propaganda were a major part of the War of Independence. In the December 1918 general election, the Sinn Féin party won seventy-three of the 105 Irish seats in the House of Commons. The party won all nine seats in the eight Cork constituencies. Among those elected were Liam de Róiste and James J. Walsh for Cork city, Michael Collins for South-Cork and Terence MacSwiney for Mid-Cork. On 21 January 1919, twenty-eight Sinn Féin deputies gathered at the Mansion House in Dublin and established an independent Irish assembly known as Dáil Éireann. At that meeting, a Declaration of Independence was adopted in which the deputies ratified the Irish Republic proclaimed on Easter Monday 1916 and pledged themselves ‘to make this declaration effective by every means at our command.’

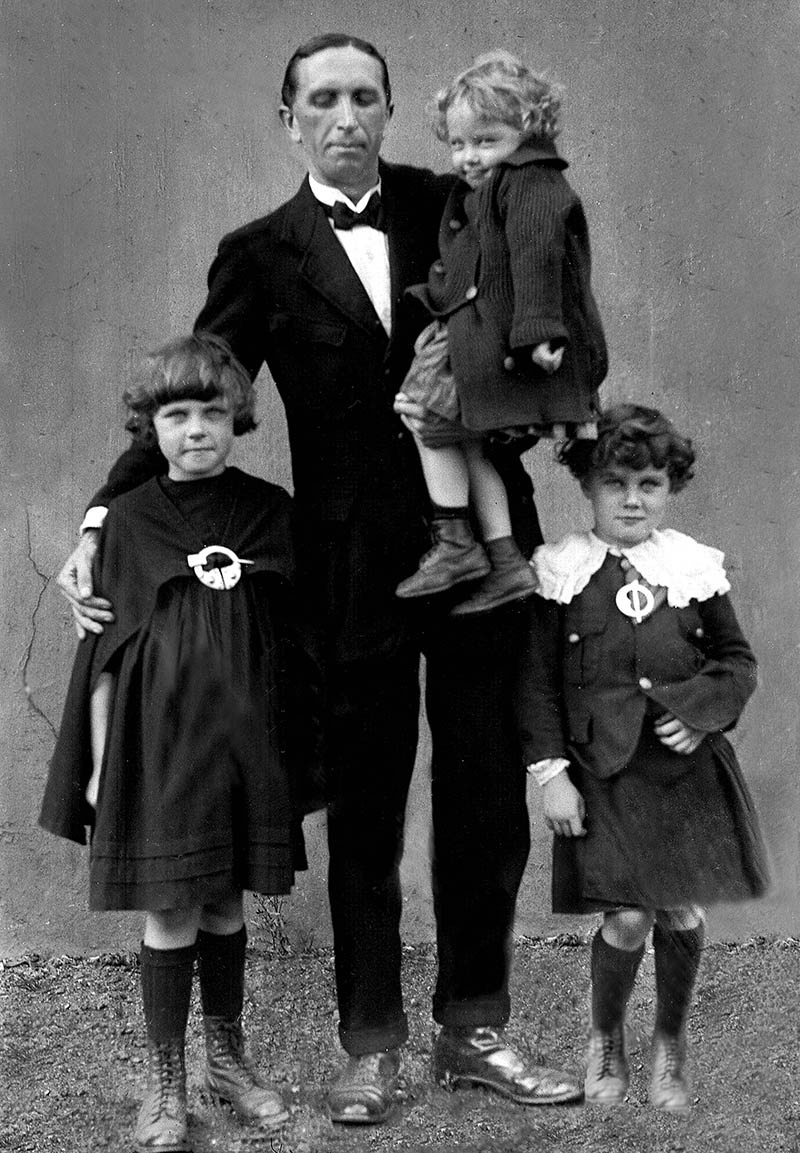

(Above) James J. Walsh and Tomas MacCurtain's children

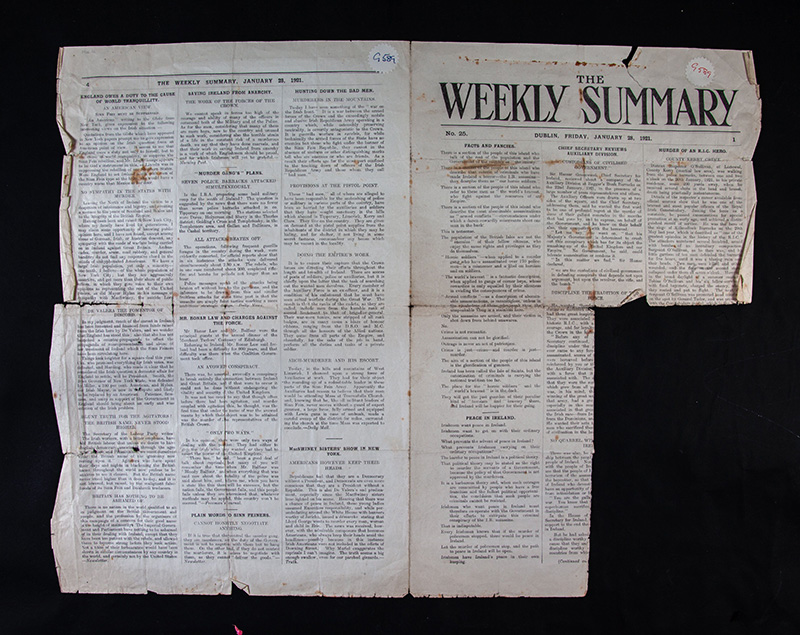

Sinn Féin deputies used Dáil meetings to publicise their campaign for an Irish Republic. After Dublin Castle suppressed the Dáil on 11 September 1919, meetings were held in secret. Two months later, Desmond FitzGerald, Dáil Eireann's Director of Publicity, produced theIrish Bulletin newspaper. Widely distributed, the paper emphasised the legitimacy of Dáil Eireann and highlighted atrocities committed by Crown forces. In August 1920, Dublin Castle made an effort to win the propaganda war by producing its own newspaper. Named The Weekly Summary, it included details of the war from a British perspective, describing IRA operations as ‘outrages’ and Sinn Féin as ‘enemies of humanity’.

(Above) Copy of The Weekly Summary. No.25, published on the 28th Jan 1921

The killing of the Lord Mayor of Cork, Tomás Mac Curtáin, (20 March 1920), the death by hunger strike of his successor, Terence MacSwiney (25 October 1920) and the arson attack known as the Burning of Cork (11/12 December 1920) drew worldwide attention to the fight for an Irish Republic. MacSwiney’s successor as Lord Mayor, Donal Óg O’Callaghan, also gave evidence to the American Commission on Conditions in Ireland which generated positive publicity in the United States. These acts and the political campaign waged by Sinn Féin would have a major impact on the outcome of the conflict.

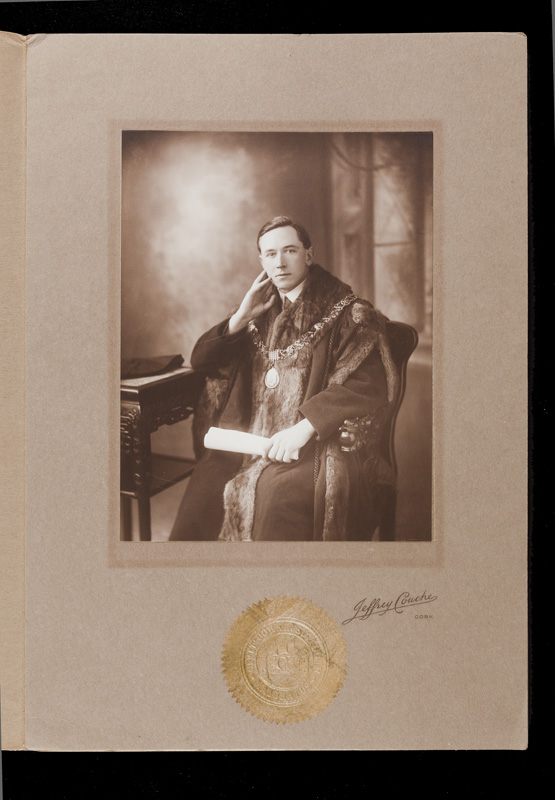

(Above) Lord Mayor Donal Og O'Ceallachain (Donal O'Callaghan)

The Intelligence War

The acquisition of accurate intelligence can be a vital element to the planning and success of a military operation. During the War of Independence, both the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and Crown forces developed their own intelligence networks. The Crown intelligence service was directed by the Irish administration in Dublin Castle, while IRA intelligence was led by Michael Collins. Appointed director of intelligence in 1919, Collins soon established a network of agents and intelligence officers in Dublin and the rest of the country. The three Cork IRA brigades all had their own intelligence officers. Florence O’Donoghue was intelligence officer of Cork No. 1 Brigade until April 1921. He organised an intelligence structure for the brigade and established a full-time intelligence squad.

(Above) Flor O'Donoghue

Dublin Castle depended on the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) to provide information on the republican movement. The British army also supplied intelligence, as did members of the civilian population. However, IRA attacks on the police and the execution of suspected spies and informers dramatically reduced the amount of information coming from these sources.

(Above) University College Cork's Historian, Dr. John Borgonovo , gives an overview of the Intelligence War

In the Cork No. 1 Brigade area of operations, both sides had successes and failures in the intelligence war. In 1921, information obtained by informers enabled Crown forces to successfully ambush IRA units at Dripsey (28 January), Mourne Abbey (15 February), Clonmult (20 February) and Ballycannon (23 March). However, when some senior IRA officers were captured in a raid on Cork City Hall on 12 August 1920, with the exception of Terence MacSwiney, all were subsequently released. For its part, IRA intelligence identified and executed important British agents such as Henry Quinlisk and Patrick ‘Cruxy’ O’Connor. It also managed to place agents in railway stations, hotels, post offices, in the police and in the center of the British military establishment in Victoria Barracks. There was also a ‘tapping station’ set up in a cottage in Blarney that enabled the IRA to listen in on telephone calls.

(Above) Part of a British field telephone from Castletownroche

(Above) Dr. John Borgonovo from University College Cork, gives us an insight into the activities of spies and informers

War in Cork - Biographies

Daniel ‘Sandow’ O’Donovan

Commandant Daniel ‘Sandow’ O’Donovan

Cork No. 1 Brigade, IRA

Daniel O’Donovan was born on Barrack Street, Cork city, in October 1892. He was the second of eight children born to John and Eliza O'Donovan (née Connolly). The family later moved to the north-side of the city and settled on the Old Youghal Road. Educated at the North Monastery, O’Donovan was later employed in Murphy’s Brewery. While there, he acquired the nickname ‘Sandow’ because of his resemblance to Eugen Sandow, the German bodybuilder who appeared on posters advertising Murphy’s Stout.

In December 1913, O’Donovan joined the Cork City Corps of Irish Volunteers. He mobilised with the Cork City Battalion on Easter Sunday 1916, in accordance with the original plans for the Rising. Following the Rising, he became known for his leadership ability and on 3 September 1917, led the raid that removed the arms stored in Cork Grammar School for its Officer Training Corps. During the War of Independence, he commanded the 1st Battalion of Cork No. 1 Brigade of the IRA, the Brigade Flying Column and the Cork City Command. He also participated in many major IRA operations including the attack on Blarney RIC Barracks (1 June 1920), the attack on King Street RIC Barracks (1 July 1920), the killing of RIC Divisional Commissioner Gerald Bryce Ferguson Smyth (17 July 1920) and the Coolavokig Ambush (25 February 1921).

O’Donovan was opposed to the Anglo-Irish Treaty. During the Civil War, he commanded Cork No. 1 Brigade of the Anti-Treaty IRA and took part in a number of operations. He later married Kathleen Roche and the couple had four children. Daniel ‘Sandow’ O’Donovan died in Mallow, Co. Cork on 31 July 1975 and is buried in St. Finbarr’s Cemetery.

Frank Busteed

Vice-Commandant Frank Busteed

6th Battalion, Cork No. 1 Brigade

Frank Busteed was born at Kilmuraheen, Doughcloyne, Co. Cork, on 23 September 1898, but he spent his childhood years in Cork City. He had a mixed religious and cultural background. His father, Samuel, was Protestant and his mother,Norah (née Condon-Maher), was Catholic. His father died when he was two years old and he was raised by his mother who came from a strong nationalist family.

In 1909/10, Busteed joined Fianna Éireann. In 1916, he joined the Blarney Company of the Irish Volunteers and, in January 1919, he became the Commander of A Company, 6th Battalion, Cork No. 1 Brigade. The following year, he became Vice-Commandant of the 6th Battalion and, in 1921, he was appointed the Commander of the Battalion’s flying column. During the War of Independence, Busteed was a judge in Republican Courts and took part in many major IRA operations. He was in command of the IRA column at the Dripsey Ambush (28 January 1921). His unit was responsible for the capture and execution of Mrs Maria Lindsay and her chauffeur, James Clarke, as well as the capture and execution of Major Geoffrey Lee Compton Smith. Mrs Lindsay, Clarke and Compton Smith were all held as captives in an effort to prevent the execution of IRA prisoners in Victoria Barracks, Cork.

Frank Busteed fought with the Anti-Treaty IRA during the Civil War. In 1924, he emigrated to the United States where he married Anne Marron. The couple raised six children and, in the 1930s, they moved to Cork City. During the Emergency, he served in the Defence Forces with the rank of Lieutenant. He died on 9 November 1974 and was buried in St. Finbarr’s Cemetery.

Maria Georgina Lindsay

Maria Georgina Lindsay

Civilian

Maria Georgina Rawson was a member of a landed estate family from Baltinglass, Co. Wicklow. In 1887, she married John Lindsay, the eldest son of George Crawford Lindsay, a linen merchant from Banbridge, Co. Down. The couple moved to Leemount House and Estate in Muskerry, Co. Cork, when John Lindsay purchased it in 1901. John Lindsay passed away in 1918, leaving his wife to manage the estate with her butler and chauffeur, James Clarke.

Maria Lindsay was a woman of strong unionist convictions. She would also have been known to the British officers in Ballincollig Barracks and to Major General E. P. Strickland, the General Officer Commanding the 6th Division in Cork. On 28 January 1921, she learnt that an IRA ambush party had taken up positions at Godfrey’s Cross, near Coachford. She told a local priest, Father Ned Shinnick, and also travelled to Ballincollig Barracks to inform the British Army. Father Shinnick got word to the ambush party but his warning was ignored as he had denounced the IRA in the past. Later in the day, British troops from Ballincollig surprised the ambush party and captured eight of its members. Five of those captured were later sentenced to death by a court martial.

The IRA learned that Mrs. Lindsay had informed the British about the ambush and on 17 February, Volunteers seized her and James Clarke and held them captive in an effort to halt the executions. She sent a letter to General Strickland informing him that, if the condemned IRA men were shot, then she and her chauffeur would be executed. Her plea was ignored, and the men were executed on 28 February 1921. Mrs. Lindsay and Clarke were then executed by the IRA. Their remains have never been recovered.

Michael 'Mick' Murphy

2nd Battalion, Cork No. 1 Brigade, IRA

Born in Cork on 30 March 1894, Michael ‘Mick’ Murphy was a well-known sportsman, member of the Gaelic Athletic Association and senior IRA officer. As a young man, he initially supported William O’Brien’s All-for-Ireland League but, in 1913, he joined the Irish Volunteers. On Easter Sunday 1916, he mobilised with the Cork City Battalion in accordance with the original plans for the Rising. He avoided arrest in the aftermath of the Rising and, over the next three years, spent much of his time reorganising the Volunteers.

In 1918, Murphy was sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood. The following year, he was appointed Commanding Officer of the newly formed 2nd Battalion of the Cork No. 1 Brigade of the IRA, located on the south-side of the city. During the War of Independence, he took part in many significant IRA operations including the attack on King Street RIC Barracks (1 July 1920), the Barrack Street Ambush (9 October 1920) and the Parnell Bridge Ambush (4 January 1921). He also took part in the execution of a number of suspected spies and informers.

In April 1920, Murphy took over command of the brigade flying column. On 13 June 1921, he was arrested at a public house on Douglas Street. After giving a false name, he was charged with resisting arrest and sentenced to six months hard labour to be served on Spike Island. Released on 20 November 1921, he took the Anti-Treaty side during the Civil War. After that conflict ended, Mick Murphy resumed his sporting career and went on to win a number of GAA championship medals. He died on 20 September 1968 and is buried in St. Finbarr’s Cemetery in Cork.

Peg Duggan

Captain Peg Duggan

Thomas Kent Branch, Cumman na mBan

Margaret ‘Peg’ Duggan was born in the townland of Kilnap, Co. Cork, on 8 August 1892. She was one of eight children born to Patrick and Elizabeth Duggan (née Lavery). When she was young, the family came to live on the Commons Road in Cork City but it later moved to 49 Thomas Davis Street in Blackpool. In 1912, Peg and her sisters, Sarah, Brigid and Annie joined the South Parish Branch of the Gaelic League at An Grianan, on Queen Street. They also attended the inaugural meeting of Cumann na mBan in Cork, which was held in a hall known as An Dún, which was also on Queen Street (now Fr. Mathew Street).

When the Volunteers in Cork asked that a member of Cumann na mBan be appointed captain to act outside the governing body, Peg Duggan was selected. In August 1915, she attended the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa in Dublin. Following the 1916 Easter Rising, she stored weapons for the Irish Volunteers and, over the next two years, she was active in visiting and raising funds for republican prisoners and providing further assistance to some when they were released.

During the War of Independence, Peg Duggan’s home on Thomas Davis Street was used as a ‘safe house’ and meeting place for members of the IRA. She also operated a florist shop on Parliament Street that was also part of the IRA communications network. On 20 March 1920, she was among the first to arrive at the home of Tomás Mac Curtáin to comfort his family after he was killed. During the Civil War, Peg Duggan supported the Pro-Treaty National Army. She died on 17 October 1964 and is buried in St. Finbarr’s Cemetery.

Tadhg O'Sullivan

Captain Tadhg O’Sullivan

2nd Battalion, Cork No. 1 Brigade, IRA

The son of farmers, Patrick and Kitty O’Sullivan (née O’Leary), Tadhg O’Sullivan was born on 7 January 1887 in the townland of Annagh Beg, Co. Kerry. As a young man he moved to Cork where he found work as a delivery driver. A committed republican, he soon joined the Irish Volunteers and became a leader in the Cork Branch of Na Fianna Éireann.

During the War of Independence, O’Sullivan was a captain in the 2nd Battalion of Cork No. 1 Brigade of the IRA. Following the death of Tomás Mac Curtáin, he was a member of the Coroner’s Jury that delivered the historic verdict of ‘wilful murder’ against senior members of the British government and RIC. After the inquest, he was arrested and interned in Belfast but was released after he went on hunger strike. On 8 October 1920, O’Sullivan took part in the Barrack Street Ambush. He also took part in many other IRA operations, including the capture and execution of suspected spies and informers.

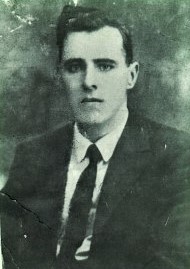

On the evening of 19 April 1921, O’Sullivan was outside No. 23 Douglas Street when he saw two plain clothes policemen and an RIC patrol converging on him. In an effort to avoid arrest, he ran across the road and up the stairs in No. 82, pursued by the police who were firing their revolvers at him. He was mortally wounded while climbing out a top floor window and he fell down into the back yard. Despite the restrictions imposed by the British authorities, on 22 April, hundreds of people lined the streets of Cork to pay tribute to Tadhg O’Sullivan when his remains were taken to St. Finbarr’s Cemetery.

Tom Barry

Commander Tom Barry

Flying Column, Cork No. 1 Brigade, IRA

Thomas Bernadine ‘Tom’ Barry was born at Kilorglin, Co. Kerry, on 1 July 1887; the second of eleven children of Thomas and Margaret Barry (née Donovan). After his father resigned from the RIC in 1901, the family moved to Rosscarbery, Co. Cork. On 30 June 1915, he enlisted in the British Army, becoming a member of the Royal Field Artillery. He went on to serve in Mesopotamia and Egypt and was demobilised on 7 April 1919. Flying Column, Cork No. 1 Brigade, IRA.

On returning to Ireland, Barry became an active member of the National Federation of Discharged Sailors and Soldiers which advocated for better conditions for ex-servicemen. In July 1920, he joined Cork No. 3 Brigade of the IRA and, in the following autumn, was appointed commander of the brigade flying column. He soon became known as an aggressive and efficient commander who mastered the principles of guerrilla warfare. Under his leadership, the column inflicted several significant defeats on Crown Forces, most notably at Toureen (26 October 1920), Kilmichael (28 November 1920) and Crossbarry (19 March 1921). Barry’s men also executed suspected informers and burned the homes of a number of loyalists as a reprisal for the destruction of the homes of local republicans.

(Above) Tom Barry in later life addressing a crowd at the unveiling of a memorial to Michael Collins at Sam's Cross