First World War British and Imperial Memorial Plaque

(Above) 'Next Of Kin' Medal/First World War British and Imperial Memorial Plaque

Origin | Acton/Woolwich |

Catalogue no: |

|

Date of Issue | 1919-1921 |

Dimensions | c.120mm in diameter |

Material | Bronze |

Manufacturer | Memorial Plaque Factory, Acton/Royal Arsenal, Woolwich. Designed by Edward Carter Preston. |

Brief Description | Memorial plague given to the next-of-kin of deceased British and Empire Service personnel who died during the Great War |

The Memorial Plaque was issued to the families of those who lost their lives serving with the British and Empire Forces during the Great War, (1914-1919). This could be in that they were designed as a form of official gratitude to the next-of-kin but were not issued until the end of the war and continued to be issued well into the 1930s. It is estimated that nearly 1.4 million medallions were issued with about 600 of these for women who had lost their life in service during the war. This amounted to about 450 tons of bronze. It is also known colloquially as ‘Dead Man’s Penny’ for its resemblance to the old British penny coin. They were also known as a ‘Widow Penny’ or ‘Death Plaque’.

The individual commemorated here on this memorial plaque is Michael Madden, who died on the November 8 1918 at age 34. He served in the Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserve onboard the HMCS Niobe. He appears that he died from an unrecorded illness. Michael was a medical assistant in the navy and likely contracted the illness from his work. He is buried at St. John’s Cemetery in Nova Scotia. Michael was born in Cork and his parents, Michael, and Mary Madden lived at 80 Tower Street, the address at which they received the plaque commemorating their son.

(Above, Left and Right) Next of Kin Medal with Original Medal Cover/Envelope

In 1917, a committee was set up to oversee the design, production and distribution of the memorial plaques. The design and style of the plaque came from an open competition held in 1917 when over 800 designs were submitted from across Britain, the Empire and even from the theatres of war. The overall winner was Edward Carter Preston. His initials E.CR.P appear above the foot of the lion.

The images depicted on the plaque were designed to convey the might of the British empire but recognises that this strength is only possible through the sacrifice of its people on the British mainland and from across its colonies. The figure of Britannia stands facing left holding a laurel wreath over a raised box in which the name of the person being commemorated is recorded. The trident and dolphins symbolise Britain’s naval prowess, while the depiction of the roaring lion represented British strength and resolve. A smaller lion is depicted underneath Britannia gnawing on a German imperial flag. The phrase ‘He (she) died for freedom and honour’ can be read around the edge of the plaque. The design was an attempt to remind the recipients of the great cause their loved ones died for.

The manufacture of the plaques was highly laborious as they were individually cast. Indeed, the exact process by which they were made is still yet to be fully understood. The production began in a factory in Acton in West London and then moved to a factory Woolwich. Those made in Acton have a thicker ‘H’ in the word ‘He’, while those made at Woolwich present a thinner ‘H’ to allow room for an ‘S’ to be added for the plaques dedicated to the women who died. A key feature of the plaque is that there is no visible ranking believed to demonstrate that all those who lost their lives during the Great War were seen as equals.

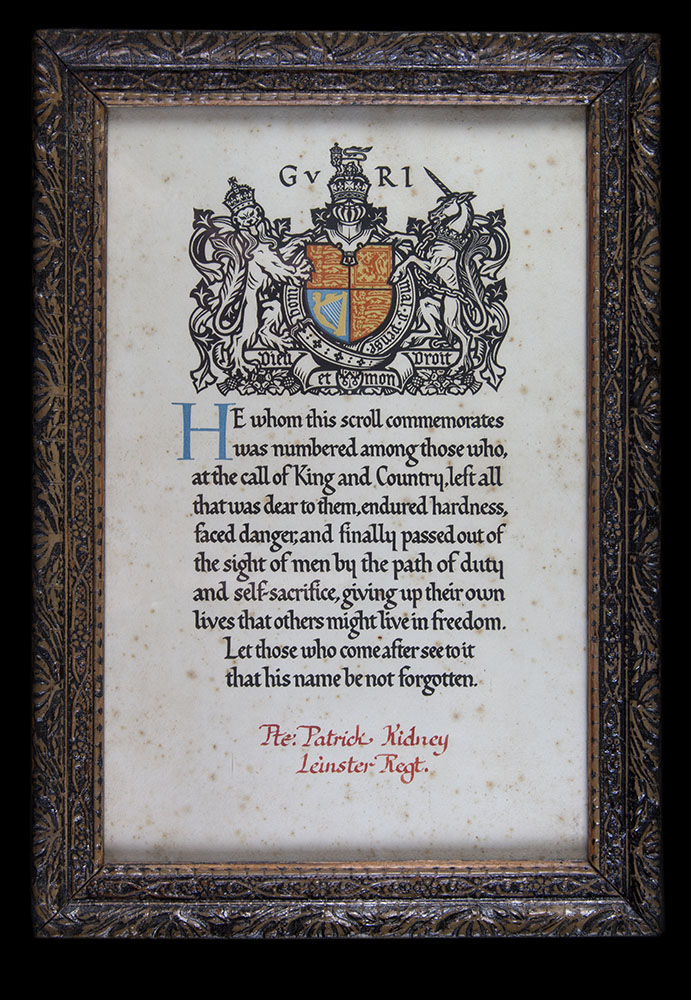

(Above) Framed 'Next of Kin' scroll, belonging to Private Patrick Kidney Leinster Regiment.

The plaque was accompanied by an illustrated scroll and together they would act as a fitting tribute for the families for their fallen loved ones. The plaque and the scroll were sent separately. Typically, both were framed and displayed in the homes, a constant remainder of the futile suffering caused by war. Unfortunately, it is believed many service personnel were not commemorated by a memorial plaque as by 1919/1920 it was impossible to trace next of kin.

After much deliberation, a text for the scroll was decided upon by the committee in charge that sets the tone and reverence that the undertaking has hoped to achieve:

“He (She) whom this scroll commemorates

was numbered among those who,

at the call of King and Country, left all that was dear to them

endured hardness, faced danger, and finally passed out

of the sight of men by the path of duty

and self sacrifice, giving up their own lives that others might live in freedom.

Let those who come after see to it

that his (her) name be not forgotten.”

Further Reading:

- Duckett, P. (2020), ‘British Military Medals: A Guide for the Collector and Family Historian’, 2nd ed. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books Ltd.

- Hughes, G. (2015). Fighting Irish: The Regiments in the First World War. Kildare: Merion Press.

- White, G. and O’Shea, B. (2010). A Great Sacrifice: Cork Servicemen who Died in the Great War. Cork: Echo Publications.

Special thanks to Deirbhile Lynch, student of 2021 MA Museum Studies - Archaeology Department UCC for her research on this object. Thanks to Gerry White for helping edit this piece.