(Above) Exhibition poster for the exhibition

The Royal Munster Fusiliers was an infantry regiment in the British Army that existed from 1881 to 1922. The regimental headquarters was in Tralee and it recruited in counties Cork, Kerry, Limerick and Clare.

During its existence, the Royal Munster Fusiliers would serve across four different continents and its members would fight and die in the Second Boer War (1899–1902) and the First World War (1914–1918). This exhibition provides an overview of the regiment to mark the centenary of 'The Munsters’ disbandment in 1922. It is a collaboration between Cork Public Museum and the students of the MA in Museum Studies programme at University College Cork.

Since disbandment, the history of the Munsters has been largely overlooked in Ireland. The political situation of the last century and its links with the British Army meant they were seen as being on the ‘wrong side of history’. As a result, the experiences and sacrifices of the men who served with the regiment are not widely known.

This exhibition endeavours to tell their story.

(Above) Munster Fusiliers soldiers wave goodbye as they leave Glanmire Road Station (Kent Station) in Cork on the 1st Nov 1914.

Courtesy of The Irish Examiner

Regimental History 1757–1898

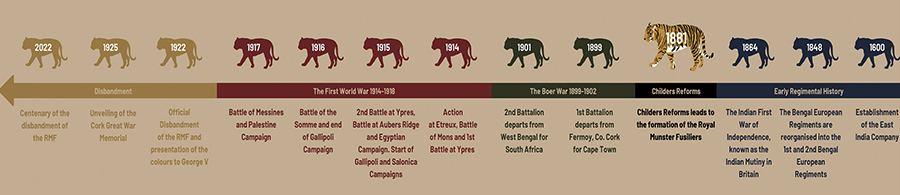

(Above) Timeline of early history

To see the fully interactive timeline of the history of the regiment, please click HERE.

(Above) Timeline of history to the present

The Royal Munster Fusiliers originated as a group of European soldiers formed in the Bengal region in 1652. Their purpose was to protect the interests of the East India Company, a private company initially founded to trade in the Indian Ocean area. Due to their rapid accumulation of wealth and influence, the East India Company raised a private army of mercenaries to help secure and control vast colonial territories in the Indian subcontinent. During this period, the East India Company conquered, plundered, and fought many battles and campaigns to further their colonial objectives. In 1756, the private army became the Bengal European Regiment. Throughout the following century, the regiment underwent various organisational changes, as can be seen in the above timeline. Control of the regiment was transferred to the British Army in 1862 and they became the 101st and 104th Regiment of Foot.

(Above) The 101st regiment of Foot Royal Bengal Fusiliers based in Rawalpindi in what is now Pakistan. The photo was taken in 1864 when the regiment took part in the Umbeyla campaign, where they violently suppressed rebellions against British rule along the border of India and Afghanistan.

Courtesy of the National Army Museum, London.

In 1881, the Secretary for War, Hugh Childers, carried out a major reform of the British Army. Numbered line regiments were renamed and grouped together to form a single regiment linked to a regimental district. In Ireland, these regiments would have two regular and three militia battalions. The soldiers of the 101st and the 104th Regiments became the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the newly formed Royal Munster Fusiliers. The South Cork, Kerry and Royal County Limerick Militias became respectively the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Battalions. With that, the Munsters completed their transition from mercenaries to a legitimate part of the British Army.

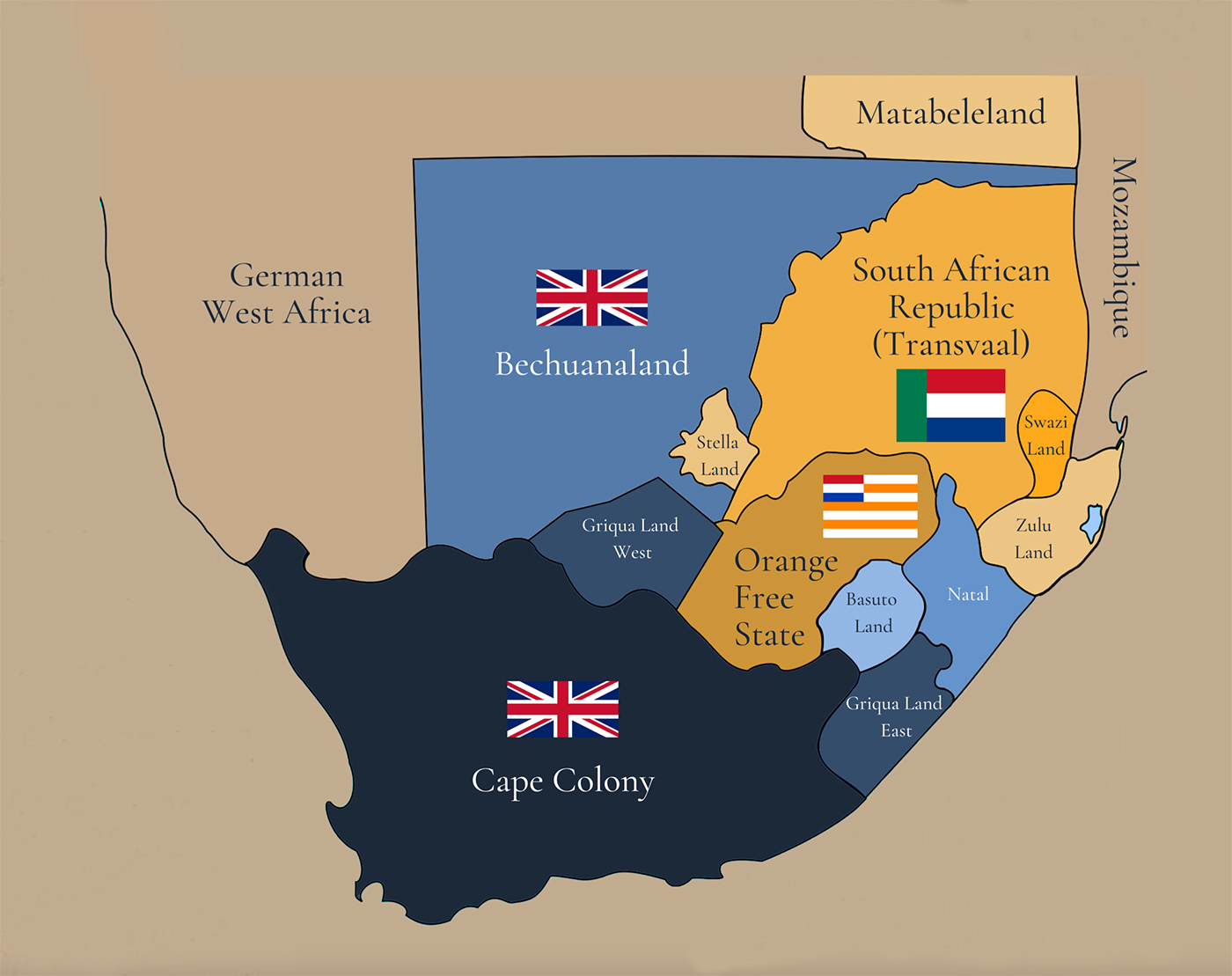

Imperial Soldiers 1899–1913

After the Royal Munster Fusiliers were established in 1881, its main task was to defend Britain’s interests both at home and throughout the British Empire. The first major conflict that the regiment took part in was the Second Boer War (1899–1902). This was fought between Britain and the two Boer (Afrikaner) republics, Transvaal and the Orange Free State. It is considered the first modern war, as the latest weaponry and technology were deployed. The Boers, which means ‘farmers’ in Afrikaans, were colonial settlers of Dutch, German and French descent. Though out-numbered and out-gunned, they successfully employed guerrilla tactics against the British Army. In response, Britain introduced internment camps, burned Boer farms, and mobilised the vast resources of its empire to secure victory.

(Above) Annexing Boer Territories of Transvaal and the Orange Free State in South Africa was the chief British objective of the war, 1899-1913.

The 1st Battalion of the Royal Munster Fusiliers left Ireland for South Africa in August 1899. During the war it took part in the British advance through the Transvaal. The 2nd Battalion left Bengal in November 1901 and upon arrival in South Africa was used to garrison blockhouses north of the Orange River Colony. On 31 May 1902, the Treaty of Vereeniging ended the war and allowed Britain to annex the two Boer republics. Records show that the regiment suffered a total of 206 casualties during the conflict. After the war ended, the 1st Battalion began a twelve-year term in India and Burma. The 2nd Battalion moved to Natal in December 1901, returned to Ireland in 1902, and then to England in 1909.

The Queen’s South Africa Medal was issued to commemorate the conflict and was given to all participants. After Queen Victoria’s death in 1901, The King’s South Africa Medal was also issued. In 1904, a Celtic Cross memorial was erected on Connaught Avenue to remember Cork men who died in the Second Boer War.

(Above) A staged photo of the Royal Munster Fusiliers in South Africa. The formation was described as a ‘bristling British front’.

Courtesy of the National Army Museum, London.

(Above) The Queen’s South Africa Medal and (right) the King’s South Africa Medal .

Many members of the 1st Battalion would have been awarded both medals.

(Above) A sand blockhouse, used to protect railroad lines from guerrilla attacks. The 2nd Battalion of the Royal Munster Fusiliers built a great number of these while stationed in South Africa.

Courtesy of the National Army Museum, London.

The First World War 1914–1918

During the First World War, members of the Royal Munster Fusiliers fought and died on the many battlefields of Belgium, France, Turkey, Greece and Palestine, including the conflicts at Gallipoli and Salonika. Britain entered the war on 4 August 1914 while the 1st Battalion and the 2nd Battalion were stationed in India and England respectively. The 1st Battalion would fight in Gallipoli in 1915, before returning to France in 1916. The 2nd Battalion were deployed to France where they fought until the war's end. The regiment’s three militia battalions were mobilised and five additional service battalions were raised during the conflict. It is estimated that 2,965 members of the regiment lost their lives as a result of the war.

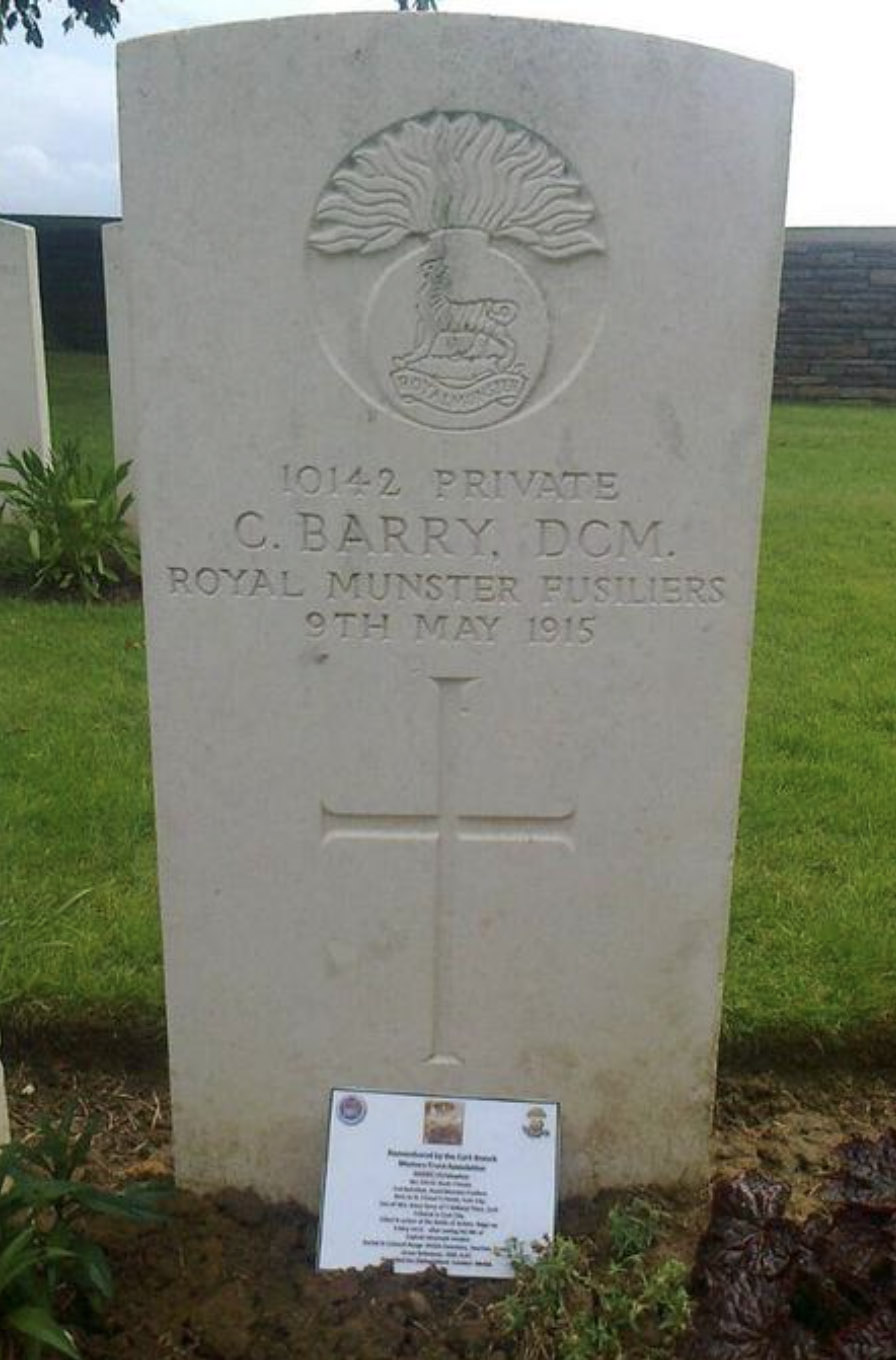

Though conscription was not imposed in Ireland, hundreds of Irishmen volunteered to serve in the Royal Munster Fusiliers. Motivated by a variety of personal and political reasons, men left their families to serve in the trenches. For many, enlisting offered a steady income and guaranteed financial benefits for those they left behind. Corkonian, Private Christopher Barry joined the army to help support his mother and five siblings. In his last letter to his mother before his death, he expressed concern that she had not received the eight pence a day he had allocated her from his pay.

To deal with the horrors of war, many soldiers took solace in their faith and support from chaplains. The chaplains were valued members of the regiment, performing important duties such as conducting religious services, administering sacraments and writing letters to the families of fallen soldiers. Though chaplains did not fight, the stories of Fr Francis Gleeson and Fr Tom Duggan are a testament to their courage and the compassion they displayed to all members of the Royal Munster Fusiliers, regardless of denomination.

(Above) Headstone of Private Christopher Barry (20) who fatally shot while saving an officer during the Battle of Aubers Ridge, 9 May 1915

Courtesy of Daniel Breen

(Above) The now lost painting, 'The Last General Absolution of the Munsters at Rue du Bois', by Fortunino Matania. It shows Fr Gleeson granting forgiveness to the Munsters before the battle.

Courtesy of the British Newspaper Archive, The Sphere and the Artist

(Above) Sergeant Major John Ring and Second Lieutenant Maxwell Rabone, Royal Munster Fusiliers (Jordeson Collection)

(Above) The Cloth Hall in Ypres Belgium, at the end of the First Battle of Ypres. Members of the RMF fought and died during this battle.

Courtesy of Photo Antony, Ypres.

The children of Cork celebrated the Munster heroism at the Battle of Ypres with the song

The Kaiser Bill tried very hard,

When he lined our front with the Prussian Guard,

But the brave Old Munsters still fought hard and held them back at Ypres.

The Wounds of War 1919–1922

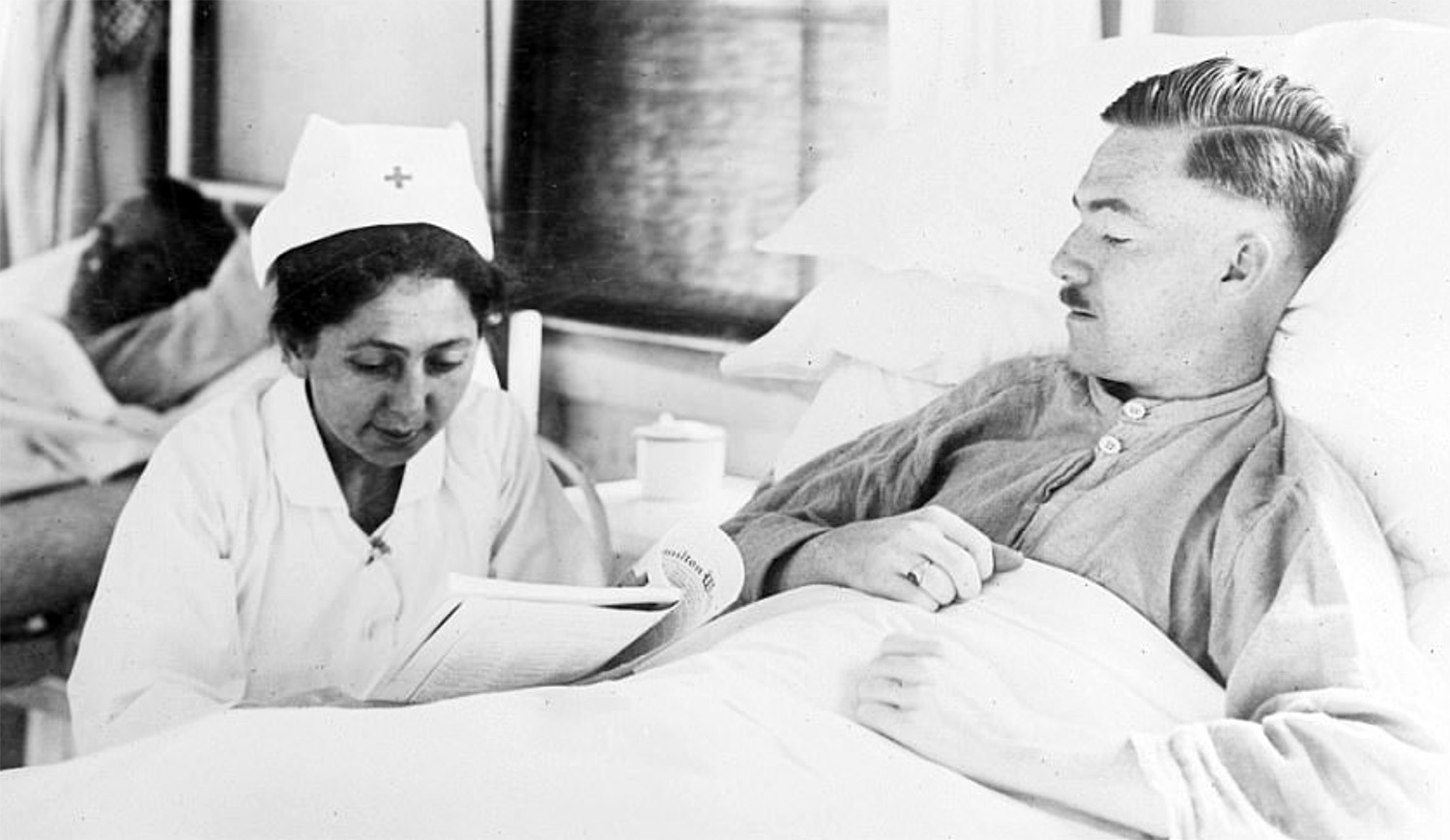

In addition to the members of the Royal Munster Fusiliers who lost their lives in the First World War, thousands returned home wounded. Many of them were disfigured or disabled, but not all of the wounds were physical. The trauma of industrialised warfare, the kind that had never been seen before, led to countless veterans developing symptoms such as fatigue, memory loss, hallucinations, and night terrors. In 1915 a form of psychological trauma called ‘shell shock’ was first recognised and diagnosed amongst soldiers in the trenches. Sufferers were often labelled as cowards and eighteen British soldiers were executed after being found guilty of this perceived offence. Some military and private hospitals made a significant effort to help those suffering from shell shock recover during and after the war. Reports imply that more than half of those admitted to these units showed rapid signs of improvement. However, a substantial minority never fully recovered from the trauma they endured. These men often described themselves as being ‘broken’ by their wartime experiences.

(Above) Many soldiers returned from the Great War with physical and mental injuries that required full-time professional care. Here a nurse is pictured reading to one of the thousands of veterans afflicted with the condition termed 'Shell Shock'.

Courtesy of Media Drum World

Some never received treatment for their psychological wounds. Instead, these men brought the battlefields home, waging their own war against the pain they suffered. Many families also struggled to help their loved ones rebuild their lives.

Private James Hayes was discharged from the Royal Munster Fusiliers in 1919 on grounds of ‘insanity’. Upon returning to Ireland, he was admitted to Our Lady’s Mental Hospital in Cork as his family were unable to care for him. Like many veterans, he would spend the rest of his life in hospital. His medals, abandoned and forgotten, were recovered from the asylum after its closure and donated to the museum in 2017. Countless others like him never fully recovered from the trauma inflicted by the war.

(Above) Sergeant Sweeney, Royal Munster Fusiliers (Jordeson Collection)

(Above L to R) The 1914-1915 Star Medal, British War Medal 1919 and the Victory Medal 1919, belonging to James Hayes (Our Lady's Hospital Collection).

(Above) Aerial photo of the Eglinton Lunatic Asylum, built in 1852. Later known as Cork District Mental Hospital, Cork Lunatic Asylum and eventually Our Lady’s Psychiatric Hospital, from which James Hayes’ medals were recovered.

(Our Lady's Hospital Collection)

A Forgotten Regiment? 1922–Present

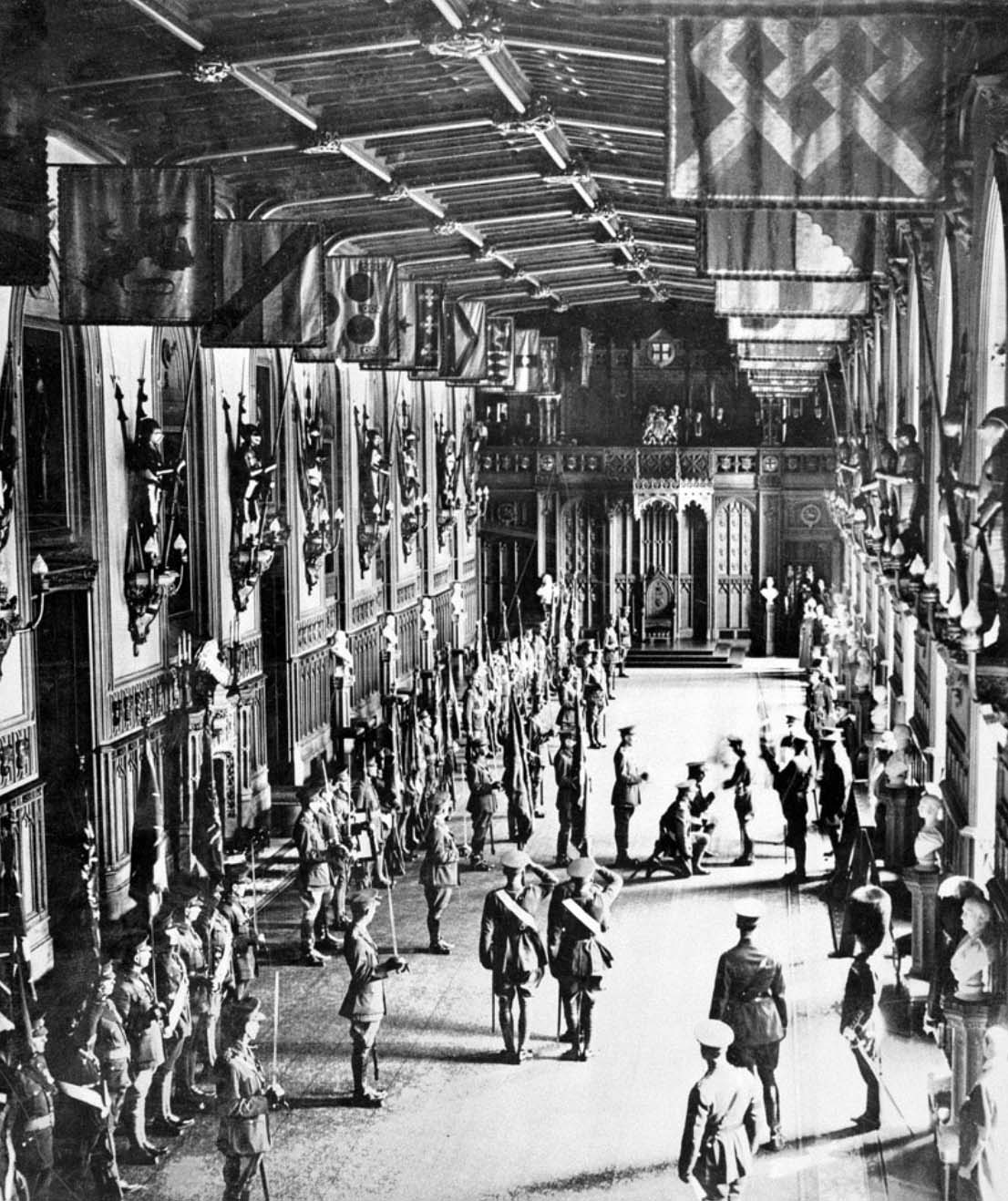

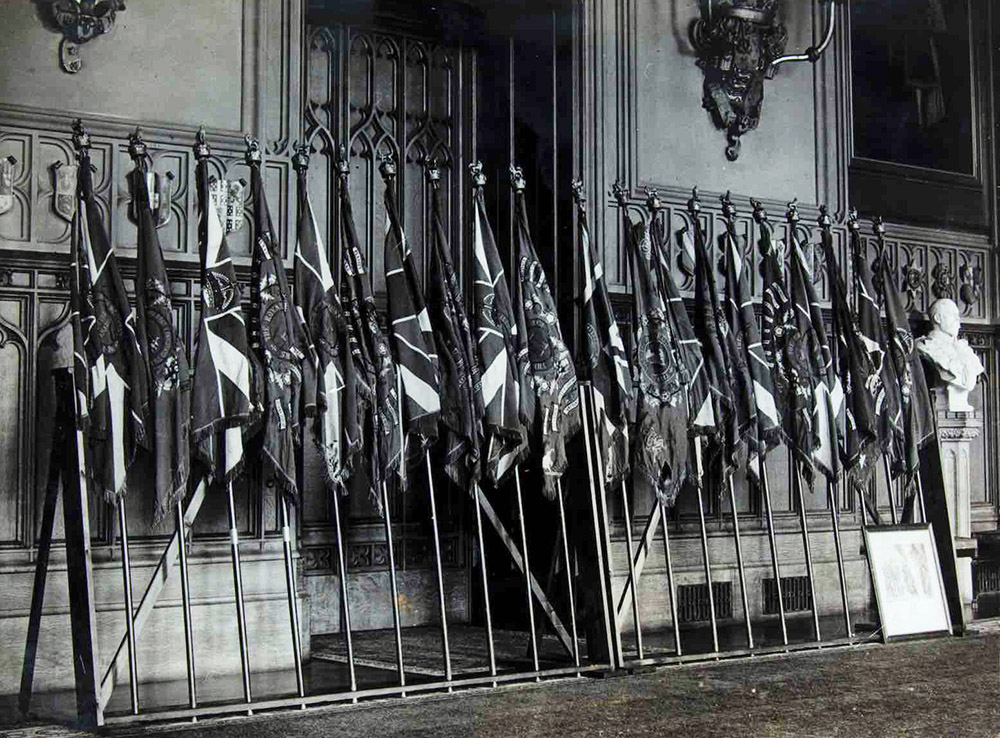

Following the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1922, the British government disbanded all the Irish regiments based in the Irish Free State. On 12 June 1922, a ceremony was held in Windsor Castle during which the Colours of the Royal Munster Fusiliers were presented to George V. The regiment was officially disbanded on 31 July 1922. The veterans who returned to Ireland after the regiment was disbanded had to adjust to a different political reality brought about by Ireland’s fight for independence. While these men left for war as heroes, upon their return they were often viewed as having fought for the enemy. While some veterans had joined the Irish Republican Army, many others joined the ranks of the pro-Treaty National Army and fought in Ireland’s Civil War. There were veteran organisations such as the Royal Munster Fusiliers Old Comrades Association and the Royal British Legion that ex-servicemen could join. Members of these organisations often attended events that were held on or near 11 November to remember their comrades who died in the First World War.

(Above) The Royal Munster Fusiliers presenting their colours to George V at a ceremony at Windsor Castle upon their disbandment in 1922.

Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

In the years following the end of the First World War, the remains of the Munsters who had died in the conflict were recovered and buried in cemeteries opened by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The names of those whose remains were not recovered are inscribed on memorials such as the Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium. In 1924, a monument was erected in Ypres to commemorate the men from Munster who died in the war. The following year, a war memorial was erected on the South Mall in Cork by the Cork Independent Ex-Servicemen’s Club. Today the regiment’s history is kept alive by organisations such as the Royal Munster Fusiliers Association and the Western Front Association.

(Above) The Munster Memorial at St. Martin’s Cathedral in Ypres, Belgium. It was constructed to commemorate all the men from the province of Munster who died during the Great War.

Courtesy of Photo Antony, Ypres.

(Above and right) The Cork Great War Memorial being unveiled on St. Patrick's Day 1925.

(Cork Camera Club Collection)

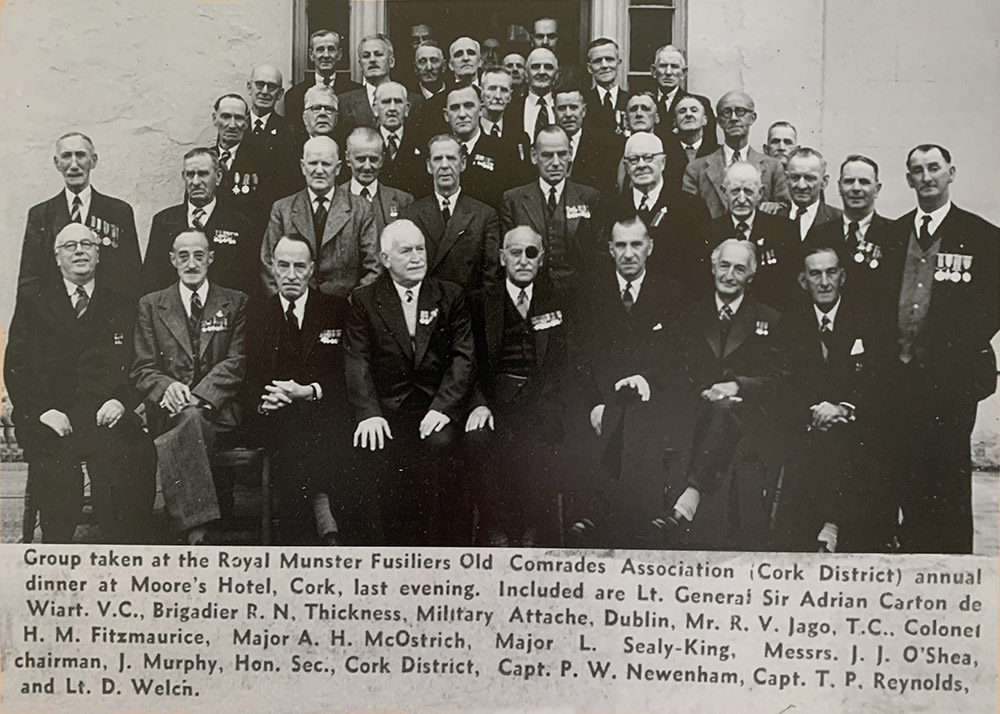

(Above) First World War service members at an annual dinner held by the Royal Munster Fusiliers Old Comrades Association in Moore’s Hotel in 1958.

Courtesy of Gerry White

Tigers, Shamrocks & Dirty Shirts

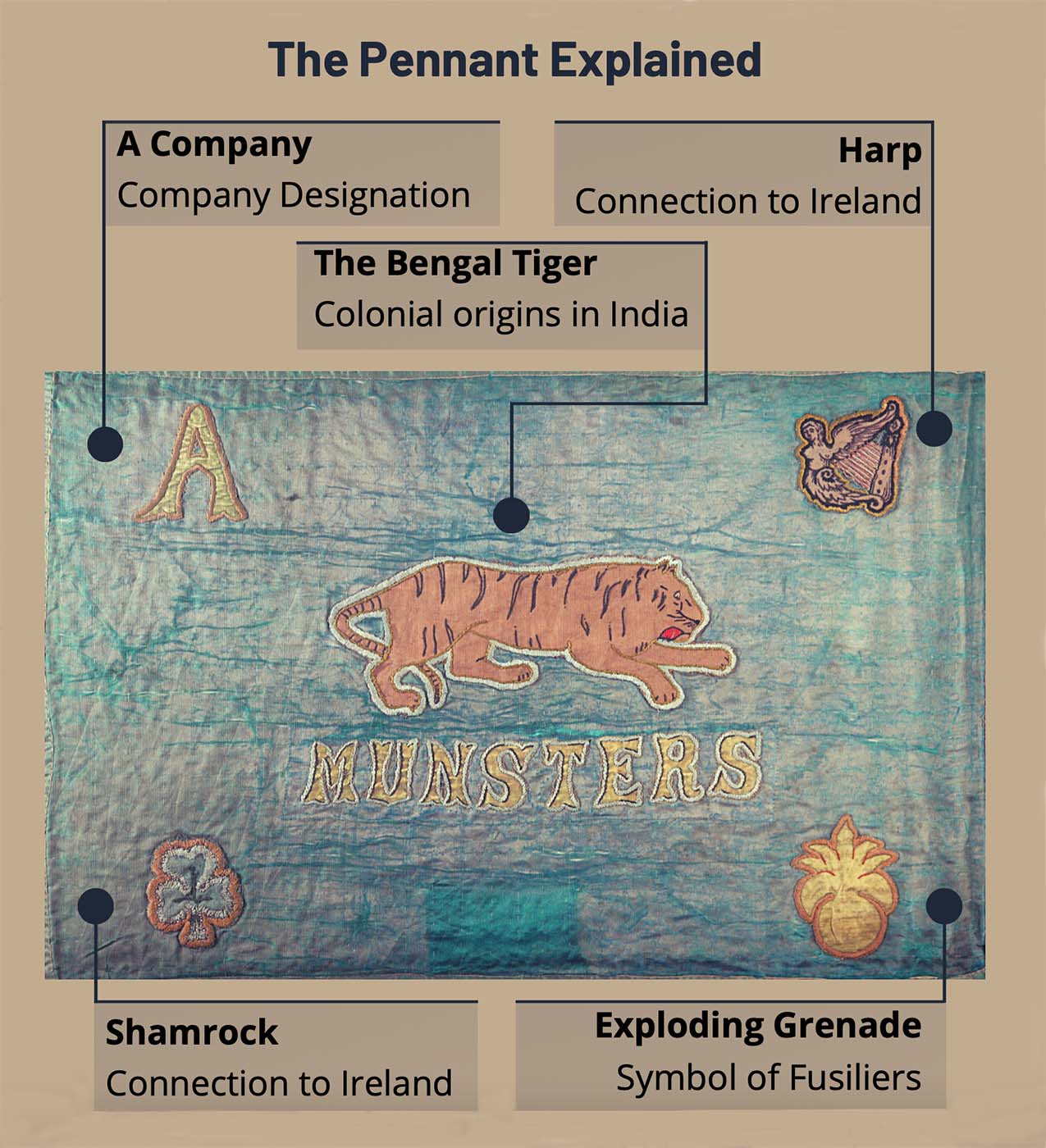

Like all regiments in the British Army, the Royal Munster Fusiliers had their own insignia, regimental colours (flags), company pennants, nickname, motto and regimental march that reflected its origins, identity and history. These all combined to foster a sense of pride in the regiment.

The insignia found on the Royal Munster Fusiliers’ regimental colours, buttons and cap badge reflected its origins as a private army for the East India Company. They also showed its military designation as a fusilier regiment and its Irish identity. These insignia included a Bengal tiger, an Irish harp, a shamrock and an exploding grenade, which was a symbol used by all fusilier regiments.

The regiment’s nickname, ‘The Dirty Shirts’, also originated in India when, due to the heat, the Bengal Fusiliers discarded their tunics and fought in their grey shirts. The regimental motto, Spectamur Agendo, ‘Let us be judged by our acts’, reflected the pride and loyalty its members had for the regiment. The regimental march, ‘St Patrick’s Day’ also identified the unit as an Irish regiment.

Each battalion carried two colours, a King’s or Queen’s Colour and a Regimental Colour. The King's Colour was a union flag trimmed with gold fabric with the regiment's insignia in the centre. It served to remind all ranks of their loyalty and duty to the sovereign. The Regimental Colour was blue, trimmed with gold and had the number of the battalion at its centre. The spirit of the regiment was embodied in these colours. They served as a rallying point and contained the regiment’s ‘battle honours’. These were the names of battles or campaigns that the regiment took part in. They were awarded in recognition of the service and courage displayed by its members.

(Above and right) The cap badge displays the regiment's important symbols, identifying its military origins and roots in India. By 1915, it was common for many battalions of the Royal Munster Fusiliers to wear a cloth shamrock behind the cap badge, symbolising the regiment's strong Irish connections. (The O'Neill Collection)

(Above) Sergeant John Sweeney (4826) about to light his pipe. Sweeney died at the Battle of Aubers Ridge, 9 May 1915, along with over 150 of his RMF comrades (Jordeson Collection).

“Your colours are the record of valorous deeds in war, and the glorious traditions thereby created...By you and your predecessors these colours have been revered and guarded as a sacred trust...Your colours will be treasured, honoured and protected as hallowed memorials of the glorious deeds of brave and loyal regiments.”

King George V, addressing the Royal Munster Fusiliers before their disbandment on the 12th June 1922

(Above) The colours of the Royal Munster Fusiliers in Windsor Castle along with colours of other Irish Regiments (The Jordeson Collection)

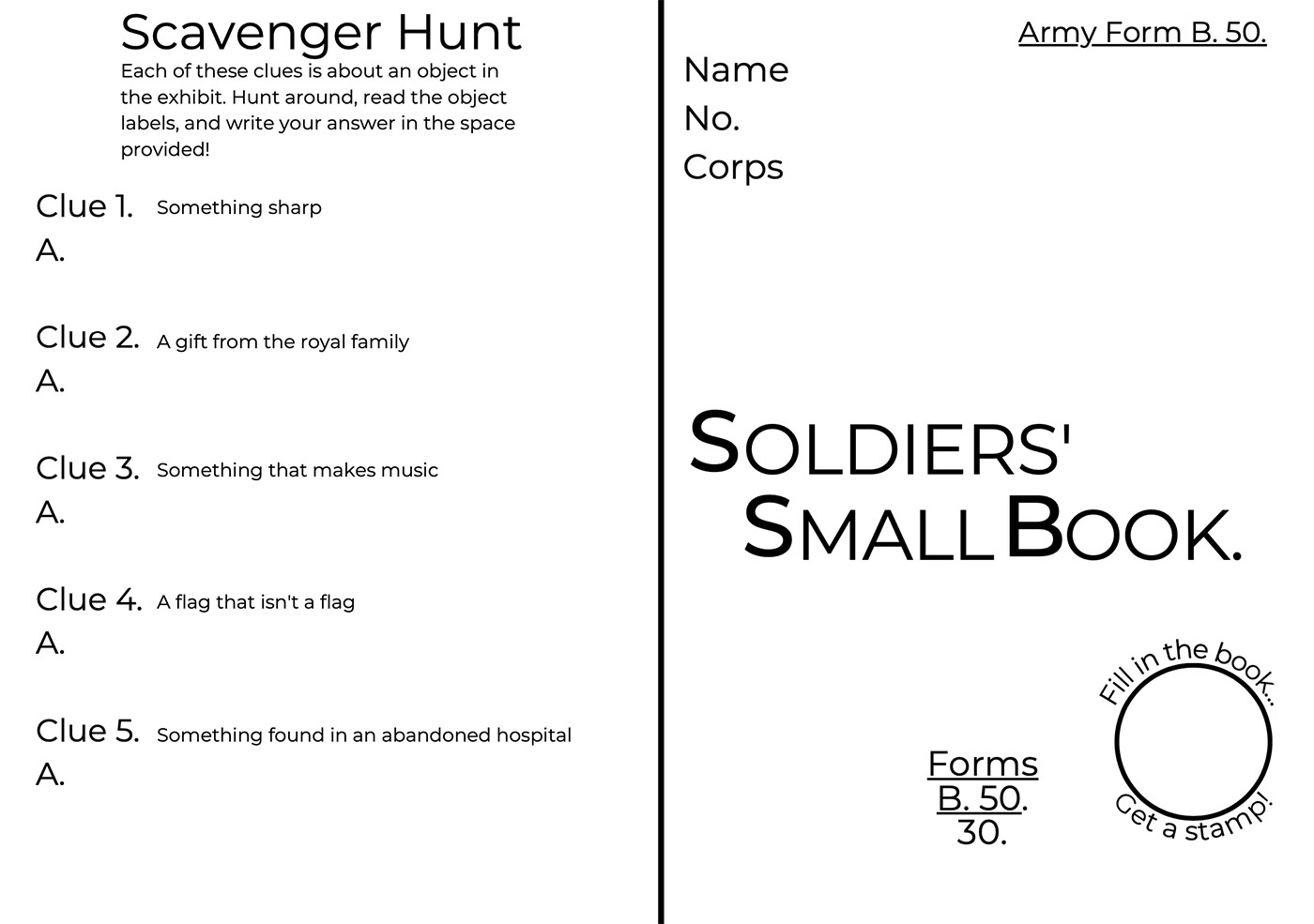

We have created a fun activity sheet for children curious about the Royal Munster Fusiliers

You can download it HERE

With thanks to the following

The MA Museum Studies class 2022 and Cork Public Museum would like to extend special thanks to the following for their help, support, and guidance throughout the process of planning this exhibition:

All Staff at Cork Public Museum — University College Cork - Gerry White -Griffin Murray — Margaret McCabe — UCC Archaeology Department — Cork County Council - Jean Prendergast — Francis O'Connor — Eugene Power — Adrain Foley- Clíodhna Ní Mhurchú — Col Mike Dudding OBE — The Irish Examiner — The British Library Imperial War Museum — National Army Museum, London — The Wellcome Collection, London - Jennifer O’Brien — Media Drum World

Graphic design by Tara Jane Sheehan and Karoline Kvandal Byrkkeland