A collection of religious artefacts held in Cork Public Museum provides deep insight into the medieval culture and ideas of salvation that can be glimpsed through objects associated with church architecture, burial, and pilgrimage. Items discovered at the site of St Mary’s of Isle, a location of the Dominican Order, also show the stonework methods used by monastic settlements in the city. Objects made of amber or porphyry, materials that are not native to Ireland, suggest links with European trade networks and crafting cultures, which impacted the island in the medieval era.

Just outside the southern walls of the medieval city of Cork, on what became known as ‘Abbey Island’, the Dominican Order of preaching friars established a monastery in the 13th century. The ground was boggy marshland, prone to flooding, and required extensive shoring and infill prior to the construction of the Dominican house. However, the priory was well positioned, directly between the ecclesiastical centre at St Fin Barre’s Cathedral and the South Gate Bridge entrance to the city.

Construction of the priory took place in stages, with the initial building being a simple east-west oriented one-aisle church, to which was added a single transept on the north side. Rooms, such as a refectory, a chapter room, a sacristy and dormitories were built around a central courtyard, in a manner reflecting other medieval monastic and mendicant houses. During extensive renovations on the priory in the late middle ages, a tower was added to the church, and a cloister was added within the courtyard. While much of the earlier construction of the building used a durable, easily worked stone imported from Dundry in England, later elements utilized limestone sourced from local quarries.

The base of a column, shown in the exhibition, is made of the Irish limestone and has the form of two octagonal pieces fused together on one side, creating a dumbbell shape. They served as the base of columns which supported the arcade of the cloister. In monastic buildings, the cloister served as the central hub of the monks’ or friars’ life, around which the activities of everyday work and religious practice took place.

The voussoir, decorated with a finely carved rosette and cut from Irish limestone, was a segment of an arch that was probably positioned over a prominent door. These Rosette carvings were unique in the medieval Irish world but have parallels to examples found in England.

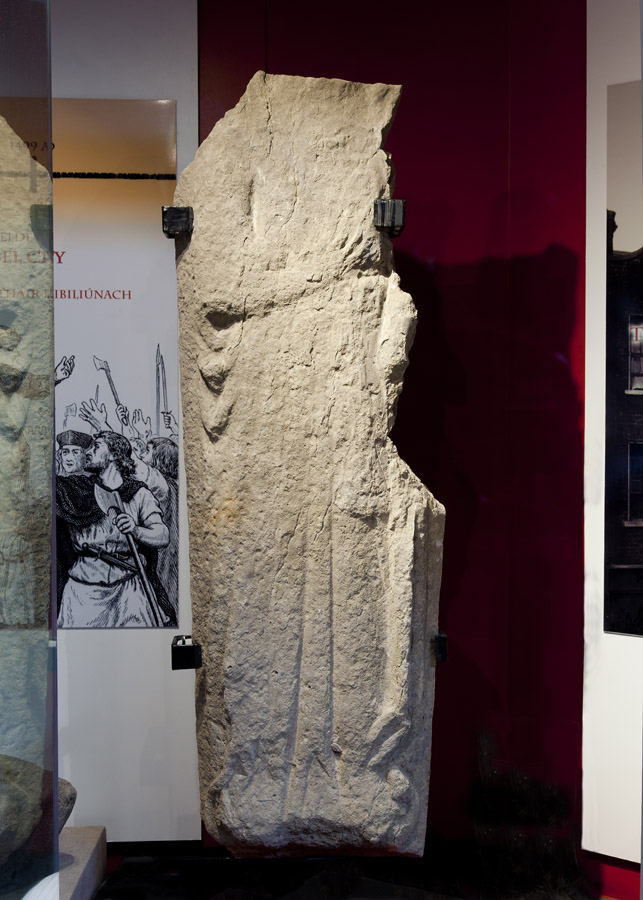

Effigies were used as part of tombs and became popular from the 12th century. They were representations of the deceased carved on top of a tomb. Two effigies were discovered at the St Mary’s of the Isle site. Displayed alongside the effigies are stone fragments of a sarcophagus found on the same site. It is possible that the effigy lids and stone fragments belonged to the same sarcophagus, although during excavations they were not found as part of their original tombs. The two effigies were used as foundation stones in later walls, which caused damage to their headpieces.

Despite damages, we can identify one of the figures as female. The woman is dressed in a robe and wears a brooch necklace, her right hand is raised, and her left hand is to her side. The woman also has a purse and what seems to be a knife. The overall appearance of this effigy is common to other examples from Europe in this period. This effigy could be based on a representation of Margaret of Gloucester, the wife of Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy, who was shown carrying a purse with coins for the poor, and a kitchen knife. The iconography of the Cork effigy could have resulted from the Anglo-Norman influences and the city’s strengthened relationships with foreign cultures through trade and politics.

With the submission of the Irish kings to King Henry II, the role of the High King of Ireland was no longer legitimate. Centralisation of power in England, the rise of feudalism, and the Papacy’s desire to centralise Christendom, eventually caught up with Ireland. With such changes the Gaelic and Hiberno-Norse cultures were forced out of the cities of Ireland and were replaced by the Anglo-Normans, or a mixture of foreign and native cultures. Cork was bound to the continent through its trade and cultural influences. This effigy, showing European trends of the 12th century, is an example of Cork’s wider links to the medieval world.

Porphyry is a semi-exotic stone that was heavily used by the Romans in decorating buildings because of its vibrant visual impact. Two varieties were common, green, and red porphyry. Porphyry, as an attractive stone which was commonplace in ancient Roman construction, but nearly non-existent elsewhere, served effectively as both proof of a visit to Rome, and a pleasing pilgrim’s relic. Porphyry fragments often showed signs of carvings which had been made in earlier days.

In medieval Christendom, it was common for people to undertake pilgrimages, which were expensive and dangerous journeys to religious sites. In the late medieval world, there were two most prestigious locations to visit. These were Rome, the capital of the Christian faith and the home of the Holy See; and Jerusalem, which between the late 11th and 15th century was controlled by either Christian Crusaders or Muslim rulers.

As with modern tourists, medieval pilgrims often sought to bring back a record of their journey: a token, a relic or even a fragment of a building in memory of their visit. Fragments of porphyry have often been encountered in religious sites within Ireland, suggesting that pilgrimage to Rome was undertaken either by members of ecclesiastical orders or lay people who were buried on the ecclesiastical site.

On display with the porphyry fragment is a token of pilgrimage: a badge depicting St Thomas Becket. As popular souvenirs, these badges were easy to produce and the Canterbury badge is an example of a pilgrimage token associated with a site that became frequently visited after the canonisation of Becket in the late-12th century. These badges allowed pilgrims to not only identify themselves as devout travellers, but also showed their devotion to a particular saint, and acted as a memory of their journey. Because Cork was a port-town, many pilgrims departed from it on their journey to holy places.

With the increasing popularity of the Canterbury pilgrimage, it is no wonder that such an item would make its way to Cork, but there was also a likely foreign pilgrim presence in the city at the time. The city’s patron saint, St Finbarr, founded a local monastery in 606, and there is a pilgrimage site associated with him at Gougane Barra. There were also pilgrimages to Our Lady of Graces in Youghal, an ivory plaque depicting the Virgin Mary and Christ, dated to the 14th century. Another local pilgrimage site, dedicated to St Gobnait, was located at Ballyvourney, where according to tradition Gobnait found nine white deer following a divine message. A 6th century saint, Gobnait’s influence spread across the south of Ireland from Dingle to Dungarvan in later centuries.

Alongside these pilgrimage artefacts, on display, there is a set of paternosters rosary beads, that demonstrate the importance of religion and devotion in the city. These Cork beads, together with examples from Waterford are regarded as the oldest surviving beads of that type in Europe. These beads are made from amber, sourced from the Baltic region, and it can be assumed that Cork had a healthy trade network with the continent to access such materials. There were specialised amber workers in France in the Middle Ages, but these Cork beads were probably crafted in Ireland.

Further Reading:

Harbison, P., Pilgrimage in Ireland: The Monuments and the People, Syracuse University Press, 1995.

This special online exhibition has been compiled by

Emmanuel Alden, BA in History from Kutztown University, Pennsylvania. He is presently an MA student in Medieval History, University College Cork.

David O’Mahony, BA in History & Geography from University College Cork. He is presently an MA student in Medieval History, University College Cork.

All images by Dara McGrath for Cork Public Museum

This online exhibition has been compiled as an online version of the exhibition that is on display in the permanent gallery of Cork Public Museum

Acknowledgments

This project is funded by Fáilte Ireland, Ireland’s Ancient East and Cork City Council.

![]()

.

.