Tomás Mac Curtáin was born at Ballyknockane, Co. Cork, on 20 March 1884. He was one of twelve children born to Patrick and Julia Curtin. When he was thirteen years old, he came to live in Cork City with his sister and was educated at the North Monastery. At an early age he developed a love of Irish culture and joined the Blackpool Branch of the Gaelic League in 1901. He married Éilís Walsh, a fellow member of the Gaelic League, in 1908 and they would have six children.

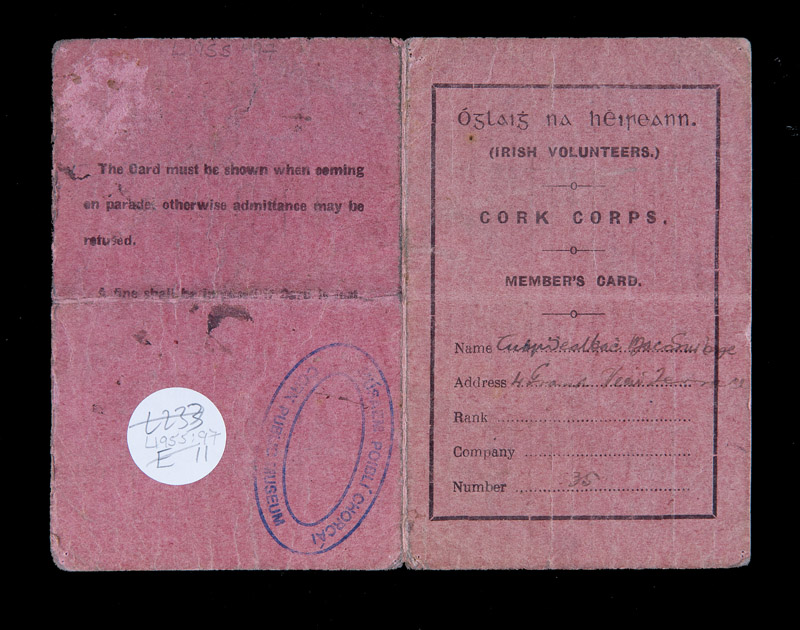

As he grew into adulthood, MacCurtáin came to believe that Ireland should sever its connection with the United Kingdom. This belief led him join the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1906 and the Cork Branch of Sinn Féin in 1907. He formed the Cork Branch of Fianna Éireann in 1911 and attended the inaugural meeting of the Cork City Corps of Irish Volunteers in December 1913, becoming a member of its executive committee. He remained with the Irish Volunteers when the movement split in September 1914 over the issue of participating in the First World War. In 1915, he became Commanding Officer of the Cork Brigade. Because of a series of conflicting orders, issued from Volunteers Headquarters, the brigade failed to take part in the 1916 Rising.

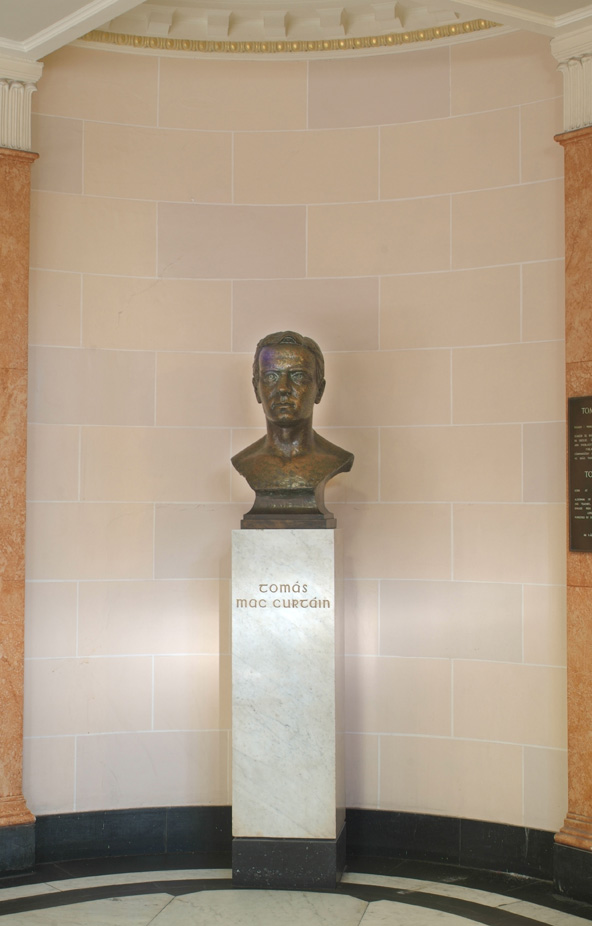

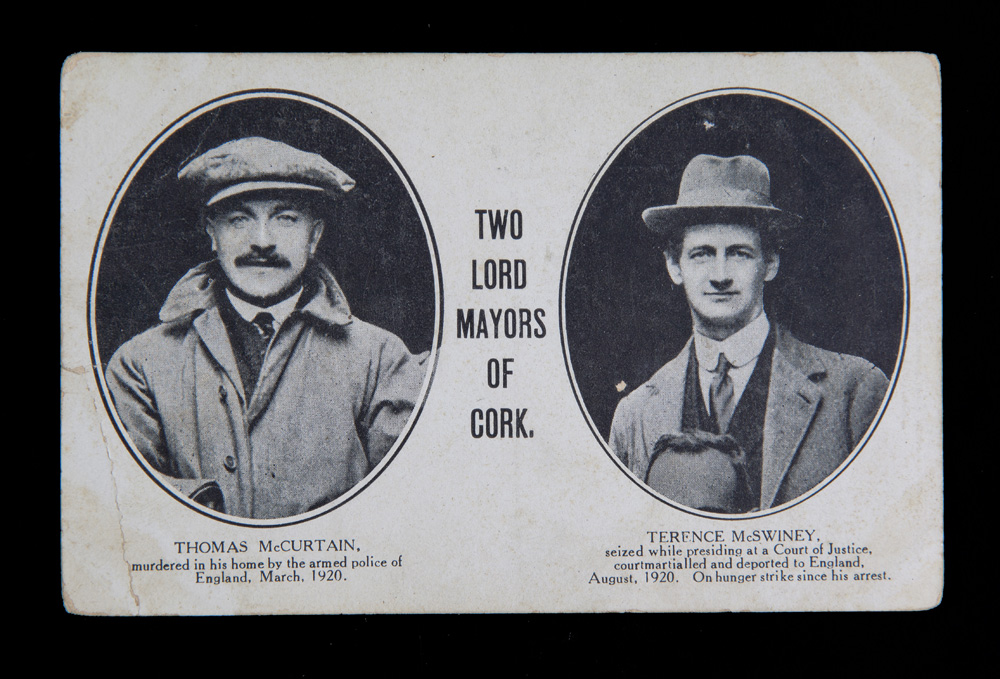

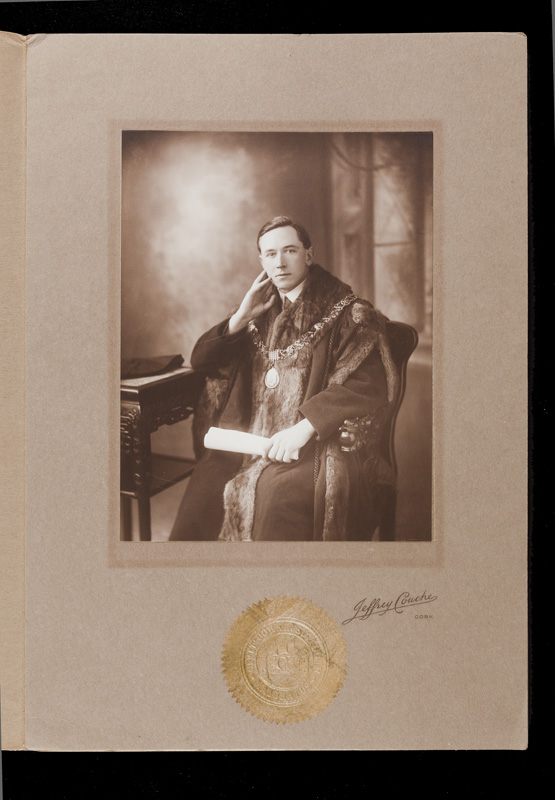

In the aftermath of the Rising, MacCurtáin was arrested and interned in Britain. Following his release in December 1916, he resumed his activities with the Volunteers. Early in January 1919, the Irish Volunteers in Co. Cork were reorganised and MacCurtáin became the Commanding Officer of the newly formed Cork No. 1 Brigade. When municipal elections were held in Cork on 15 January 1920, he was elected Alderman in the Blackpool Electoral Area. On 30 January 1920, Tomás MacCurtáin was elected the first Republican Lord Mayor of Cork.

Terence MacSwiney was born at 23 North Main Street, Cork, on 28 March 1879. He was one of eight children born to John and Mary MacSwiney. Educated at the North Monastery, he left school at the age of fifteen to help support his family after his father moved to Australia. However, his love of education led him to continue his studies part-time and, in 1907, he obtained a degree in Mental and Moral Science from University College Cork. Like many young men at that time, MacSwiney developed a love of Irish culture and a belief that Ireland should be an independent nation. In 1901, he was a founding member of the Cork Literary Society. He also became a member of the Cork Dramatic Society and they produced his first play in 1910.

In December 1913, MacSwiney attended the inaugural meeting of the Cork City Corps of Irish Volunteers and, like Tomás MacCurtáin, became a member of its executive committee. He also remained with the Irish Volunteers after the movement split in September 1914. In the summer of 1915, he left his job with The Cork Committee of Technical Instruction to become a full-time organiser for the Volunteers. MacSwiney was second-in-command of the Cork Brigade at Easter 1916. In the aftermath of the 1916 Rising, he was arrested and interned in Britain.

Terence MacSwiney returned home to Cork in December 1916 and resumed his activities with the Irish Volunteers. In February 1917, he was again arrested and sent to Bromyard Internment Camp where he remained until June 1917. While in Bromyard, he married Muriel Murphy, a member of the Cork brewing family, and the couple went on to have one daughter. He was returned as Sinn Féin TD for the constituency of Mid-Cork in the general election held in December 1918. In the municipal elections held in Cork on 15 January 1920, he was elected a councillor in the city’s Central Electoral Area.

In 1920, both Tomás MacCurtáin and Terence MacSwiney were members of the Sinn Féin party. The nationalist politician, Arthur Griffith, established Sinn Féin (‘We Ourselves’) on 28 November 1905. The party initially advocated that Ireland should become an economically self-sufficient country that would be part of a dual monarchy under the British Crown. The Cork Branch was established in December 1906. Tomás MacCurtáin joined in 1907 but Terence MacSwiney initially refused to do so as the party did not advocate complete independence for Ireland.

Although Sinn Féin got twenty-seven percent of the vote in the North Leitrim by-election held in February 1908, by 1910 support and membership had declined dramatically. However, in the aftermath of the 1916 Rising, many radical republicans joined the party. On 25th/26th October, over 1,700 delegates, including Tomás Mac Curtáin, attended a Sinn Féin convention in Dublin. The convention elected Éamon de Valera as President of Sinn Féin and committed the party to the establishment of an independent Irish Republic.

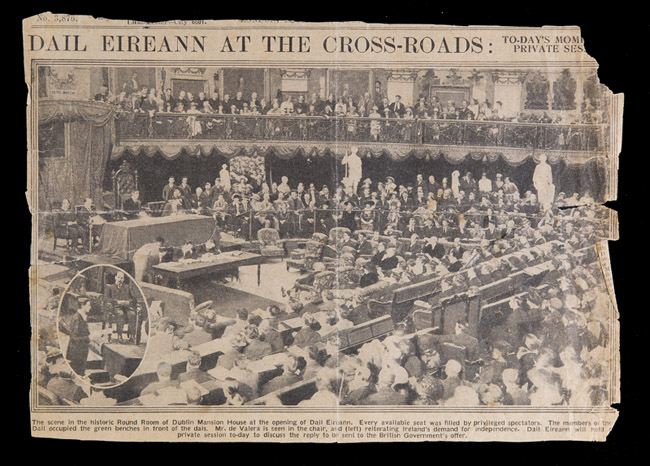

In 1917/18, Sinn Féin won six by-elections held in Ireland. It also won a sweeping victory in the United Kingdom general election held on 14 December 1918, taking seventy-three of the 105 Irish seats at Westminster. Tomás MacCurtáin did not stand in this election but Terence MacSwiney was returned unopposed in the Mid-Cork constituency. On 21 January 1919, twenty-seven Sinn Féin MPs met in Dublin and established the independent Irish assembly known as Dáil Éireann. Sinn Féin also contested the municipal election held in Cork on 15 January 1920. It ran on a joint ticket with the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union and won thirty out of fifty-six seats. Among the Sinn Féin members elected to Cork Corporation were Tomás MacCurtáin and Terence MacSwiney.

The Cork City Corps of Irish Volunteers was formed at a public meeting held in Cork City Hall on 14 December 1913. Tomás MacCurtáin and Terence MacSwiney attended this meeting and both became members of the executive committee. In February 1915, MacCurtáin became the Officer Commanding of the newly formed Cork Brigade, which encompassed the entire county. Both men were arrested and interned in Britain in the aftermath of the 1916 Rising. However, after they were released in December of that year, they began the process of rebuilding and reorganising the brigade.

Early in January 1919, Irish Volunteer Headquarters divided the Cork Brigade into three separate units. Tomás MacCurtáin was appointed Officer Commanding Cork No. 1 Brigade with Seán O’Hegarty as his second-in-command. The brigade consisted of ten battalions and had Cork City and the middle of the county as its area of operations. The 1st Battalion, which was commanded by Terence MacSwiney, operated north of the River Lee. The 2nd Battalion, commanded first by Seán O’Sullivan and later in 1919 by Seán Scanlan, operated south of the river. The home of Nora and Shelia Wallace on Brunswick Street acted as a brigade headquarters. After the establishment of Dáil Éireann on 21 January 1919, the Irish Volunteers became known as the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Following the failure of the 1916 Rising, the leadership of the IRA, under the guidance of Michael Collins, decided to fight the War of Independence using the strategy and tactics of guerrilla warfare. During 1919, Cork No. 1 Brigade didn’t conduct any significant military operations. However, in 1920 it would go on the offensive. That year, the streets and suburbs of Cork would become a battlefield as the forces of the Irish Republic engaged the forces of the Crown in a fight that would decide the future of Ireland.

On 21 January 1919, Dáil Éireann held its first meeting in Dublin. That same day, a unit of Irish Volunteers from the Tipperary No. 3 Brigade led by Séamus Robinson ambushed and killed two members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) escorting a consignment of gelignite to a quarry at Soloheadbeg, Co. Tipperary. Though unauthorised by Irish Volunteer General Headquarters (GHQ), this incident is considered to mark the beginning of the Irish War of Independence.

Following the Soloheadbeg Ambush, other Irish Volunteer units attacked members of the of the RIC and Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP). Republicans considered these organisations to be the ‘eyes and ears’ of the British administration, so their operations were designed to interrupt the supply of vital intelligence reaching their opponents. In 1919, a total of fifteen policemen were killed by the Irish Volunteers. Apart from incidents of civil unrest, Cork was relatively quiet that year. However, in 1920, all that would change.

Though pressed by his officers to take action against the RIC, Tomás MacCurtáin refused unless authorised to do so by GHQ. However, in November 1919, he received permission to launch a coordinated attack on RIC barracks in his area of operations. On the night of 2 January 1920, Volunteers from Cork No. 1 Brigade of the IRA, led by Michael Leahy, scored a major victory when they attacked and destroyed the RIC barracks in Carrigtwohill, Co. Cork. No lives were lost in this operation and the Volunteers took possession of all the arms and ammunition in the barracks. Another attack against Kilmurray RIC barracks that same night was unsuccessful and one planned against the barracks in Ballygarvan was aborted. Cork No. 1 Brigade was now at war and other operations against the forces of the Crown would soon follow.

City Engineers Report into the Burning of Cork City Part-01.pdf (size 5.8 MB)

City Engineers Report into the Burning of Cork City Part-02.pdf (size 5.3 MB)

Following its overwhelming victory in the 1918 General Election and the successful establishment of Dáil Éireann, Sinn Féin turned its attention to the municipal elections that were held on 15 January 1920. These elections were historic as it was the first time that the proportional representation voting system would be used. It was also the first time Irish women were allowed to vote in local elections.

In Cork, Sinn Féin ran on a joint ticket with the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union. Other candidates included members of the Labour Party, the Nationalist Party, Independents and representatives of ex-servicemen. Unionist candidates ran under the ‘Commercial’ banner. During the campaign, which was fought with vigour on the streets of Cork, Sinn Féin mobilised the ranks of the IRA and Cumann na mBan in support of its candidates.

When the votes were counted, the Sinn Féin/Irish Transport and General Workers Union candidates won thirty of the fifty-six seats on Cork Corporation. This was Cork’s first republican-led corporation and marked an important turning point both in the history of Cork and in the War of Independence. Sinn Fein’s success was repeated in elections held all across Ireland. This cemented its place as the main political party in Ireland in 1920. It also enabled the party to take the lead in the political struggle for an independent Irish republic. When the new corporation met on 30 January, the first task facing its members would be the election of a new Lord Mayor.

Following its overwhelming victory in the 1918 General Election and the successful establishment of Dáil Éireann, Sinn Féin turned its attention to the municipal elections that were held on 15 January 1920. These elections were historic as it was the first time that the proportional representation voting system would be used. It was also the first time Irish women were allowed to vote in local elections.

Elected-members-of-Cork-Corporation-Jan-1920.pdf (size 127.7 KB)

In Cork, Sinn Féin ran on a joint ticket with the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union. Other candidates included members of the Labour Party, the Nationalist Party, Independents and representatives of ex-servicemen. Unionist candidates ran under the ‘Commercial’ banner. During the campaign, which was fought with vigour on the streets of Cork, Sinn Féin mobilised the ranks of the IRA and Cumann na mBan in support of its candidates.

When the votes were counted, the Sinn Féin/Irish Transport and General Workers Union candidates won thirty of the fifty-six seats on Cork Corporation. This was Cork’s first republican-led corporation and marked an important turning point both in the history of Cork and in the War of Independence. Sinn Fein’s success was repeated in elections held all across Ireland. This cemented its place as the main political party in Ireland in 1920. It also enabled the party to take the lead in the political struggle for an independent Irish republic. When the new corporation met on 30 January, the first task facing its members would be the election of a new Lord Mayor.

List-of-Councillors-Cork-City-Council-City-Hall-1920.jpg (size 164.3 KB)

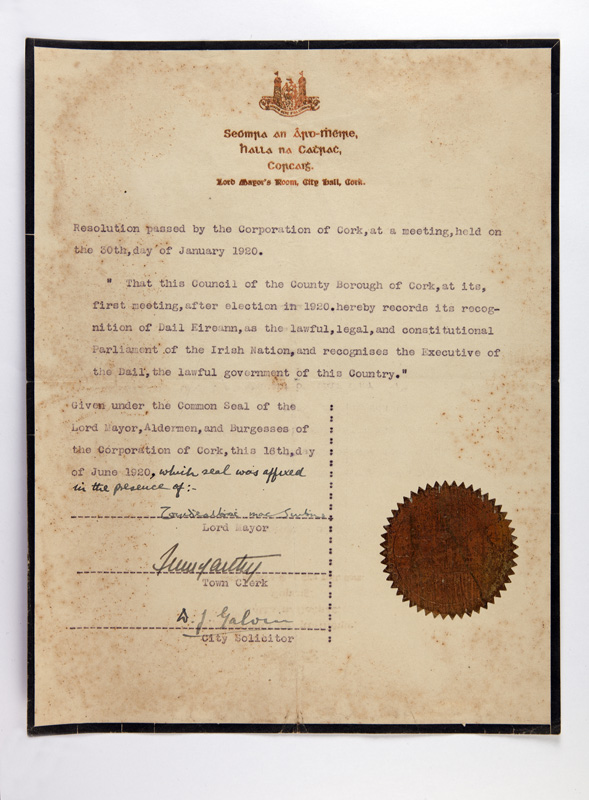

When the new corporation convened in City Hall on 30 January 1920, Sinn Féin Councillor Mícheál Ó Cuill proposed Tomás MacCurtáin as Lord Mayor of Cork for the ensuing year. Councillor Terence MacSwiney seconded the proposal, and as there were no other proposals, Tomás MacCurtáin was unanimously elected as the first republican Lord Mayor of Cork to the acclaim of his fellow councillors. All Sinn Féin members stood and sang Amhrán na bFhiann (The Soldier’s Song). The tri-colour was also flown over City Hall for the first time.

Mac Curtáin’s first act on being elected was to propose that Cork Corporation recognise Dáil Éireann as the ‘lawful, legal and constitutional Parliament of the Irish Nation’ and the Executive of the Dáil as the ‘Lawful Government’ of Ireland. His proposal was seconded by Liam de Róiste and passed unanimously. As the republican corporation did not recognise British rule in Ireland, no candidates were put forward for the position of High Sheriff of Cork. MacCurtáin also blocked a proposal to increase the Lord Mayor’s salary from £600 to £1,000, instead he agreed to a salary of £500. Two weeks after his election, MacCurtáin announced that he had revived the custom of appointing a chaplain to the Lord Mayor and that he had appointed Father Dominic O’Connor OFSC to that position.

In his short time as Lord Mayor, MacCurtáin brought great energy to the municipal administration of the city through his hard work and organisational skills. He carried out his civic duties with the same enthusiasm and commitment he showed as commander of Cork No. 1 Brigade of the IRA. Among his achievements was the establishment of a committee to examine ways to improve wages and the standard of living in the city.

Following the killing of his close friend and comrade Tomás MacCurtáin, Terence MacSwiney took over as commanding officer of Cork No. 1 Brigade of the IRA. The office of Lord Mayor of Cork had also been left vacant by MacCurtáin’s death and, on the evening of 30 March 1920, the members of Cork Corporation gathered in the City Hall to elect his successor. The meeting opened with a proposal by Councillor Liam de Róiste that Professor William Stockley of Sinn Féin take the chair. Once this was agreed, de Róiste then nominated MacSwiney as Lord Mayor. The nomination was seconded by councillors Thomas Barry of Sinn Féin and Sir John Scott, leader of the unionists. As there were no other nominations MacSwiney was deemed to be elected.

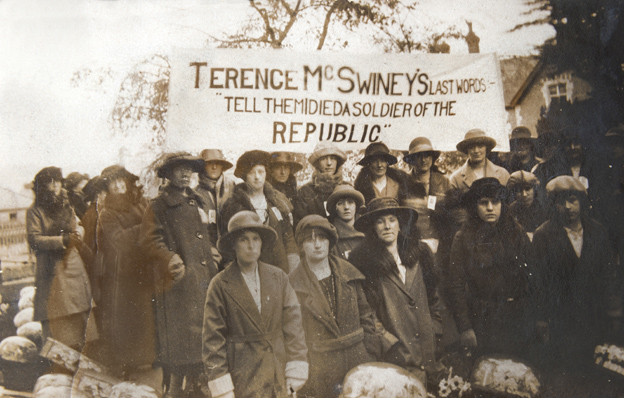

In the course of his historic acceptance speech, MacSwiney stated that he was there, ‘more as a soldier stepping into the breach, than as an administrator to fill the first post in themunicipality’. He went onto outline his views of the conflict then taking place and what he believed to be the secret of the republican’s strength and assurance of final victory declaring, ‘This contest of ours is not on our side a rivalry of vengeance, but one of endurance - it is not they who can inflict most but they who can suffer most will conquer.’

As soon as MacSwiney took office, he slept in safe houses and the IRA appointed armed guards to keep him safe from attack. In the weeks that followed, the Lord Mayor brought a motion to the corporation re-affirming its allegiance to Dáil Éireann. He also proposed a motion calling upon the Dáil to bring the verdict of the inquest held into the death of MacCurtáin to the notice of the world and to take action to ‘compel the British Army of Occupation to evacuate our country.’ Both motions were passed by Cork Corporation.

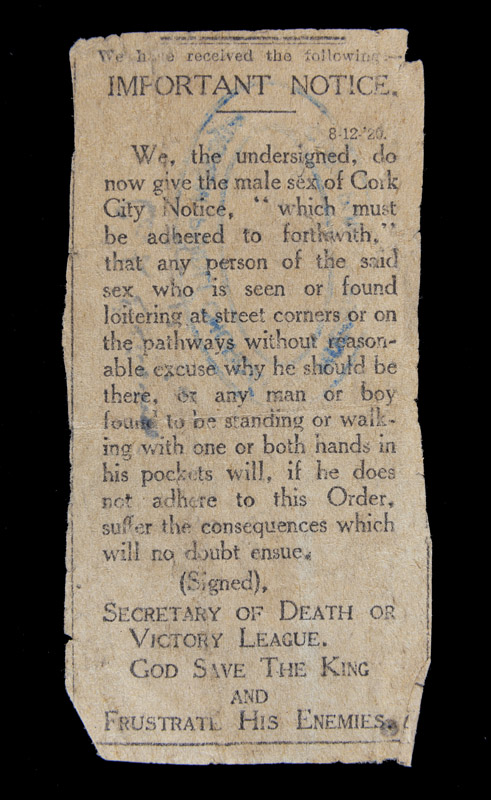

Following their successful attack on Carrigtwohill RIC Barracks on 2 January 1920, members of the IRA in Cork increased their attacks on the Crown Forces. On 18 February, Timothy Quinlisk, a former member of Roger Casement’s Irish Brigade who had been unmasked as a British spy, was executed outside Ballyphehane. Then, on the night of 10 March, RIC Inspector McDonagh was shot and seriously wounded after he left City Hall. In response to this incident, the RIC ransacked the homes of a number of prominent republicans in the city. The IRA, however, continued their attacks. On 12 March, Constable Timothy Scully was shot dead in Glanmire and, on the night of 19 March, Constable Joseph Murtagh was killed as he was walking along Pope’s Quay.

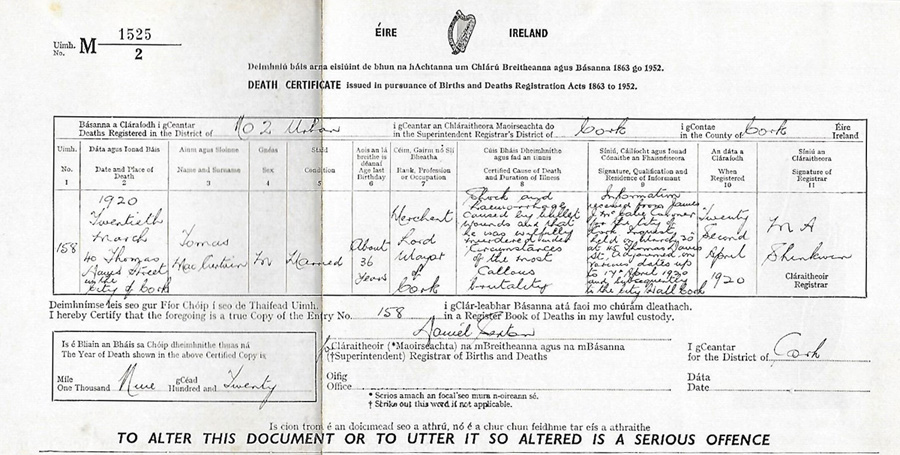

Some extreme elements within the RIC placed the blame for these attacks on Tomás Mac Curtain and decided to retaliate. Around 1am on 20 March, members of the force wearing civilian clothing and with blackened faces arrived at his home at 40 Thomas Davis Street, Blackpool and forced their way into the house. While some restrained his pregnant wife, Éilís, who had answered the door, others ran upstairs and, in front of his children and in-laws who were staying in the house, they shot and mortally wounded the Lord Mayor as he walked out of his bedroom.

The killing of Tomás Mac Curtain shocked people throughout Ireland. On 22 March, political and religious dignitaries from all over the country joined his family at his funeral Mass in the Cathedral of Saint Mary and Saint Anne. After Mass, thousands of Cork citizens lined the streets of the city to see members of Cork No. 1 Brigade escort the remains of their commanding officer to his final resting place in the Republican Plot at St. Finbarr’s Cemetery.

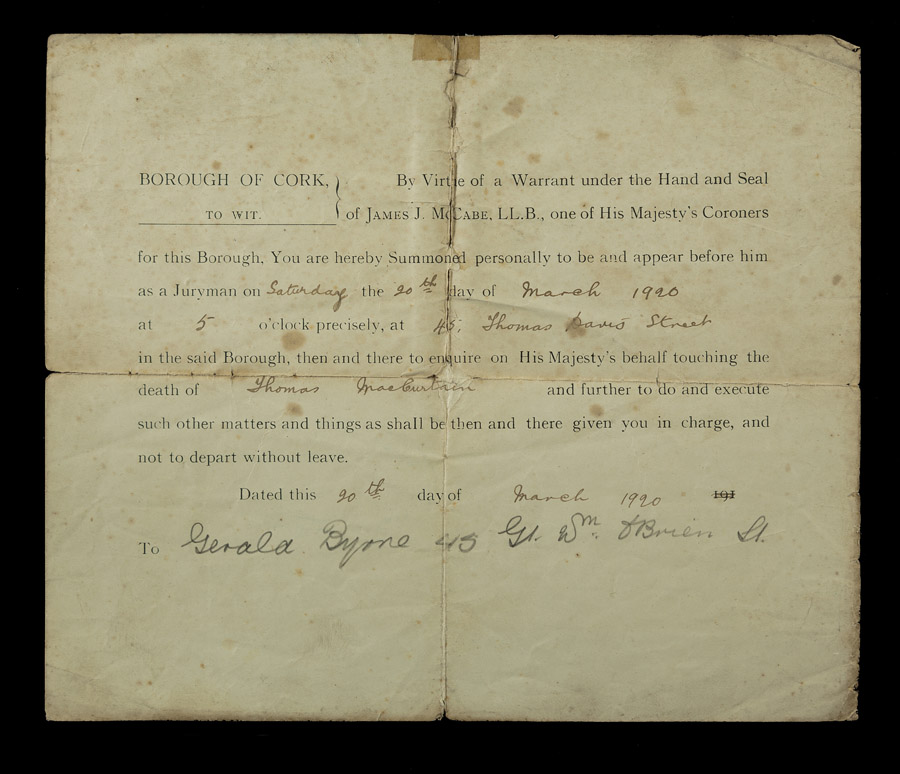

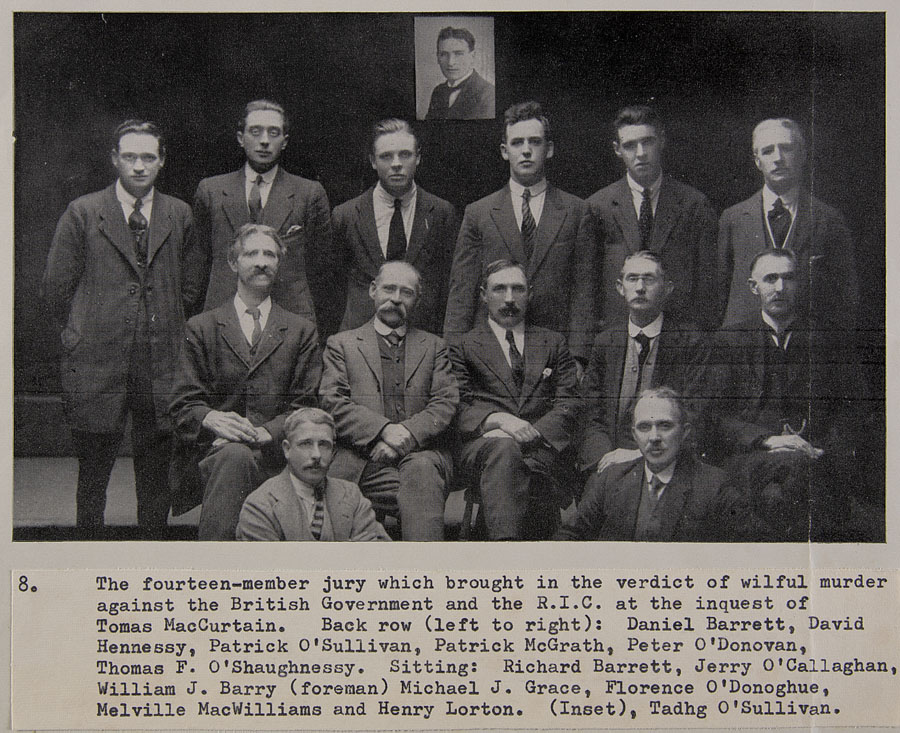

On 20 March 1920, the day that Tomás Mac Curtáin was killed, an inquest into the circumstances of his death, conducted by Coroner James J. McCabe, opened in Cork. Ninety-seven witnesses were examined, sixty-four police, thirty-one civilians and two military. Though members of the British administration said that Mac Curtáin was killed by extreme elements within the republican movement, most of the evidence given at the inquest implicated members of the RIC.

The inquest concluded on 17 April 1920 with the following unanimous verdict:

Following the murder of Mac Curtáin, RIC District Inspector Oswald Swanzy, the man who the IRA believed was primarily responsible for his death, was transferred from Cork to Lisburn. IRA intelligence eventually tracked him down. On 22 August 1920, an IRA squad, which included Seán Culhane, an intelligence officer from Cork No. 1 Brigade, shot Swanzy dead as he left Christ Church Cathedral in Lisburn.

On the evening of 12 August 1920, 300 British soldiers from Victoria Barracks surrounded Cork City Hall and conducted a search of the building. That evening, a Dáil Éireann court was in session in the council chamber and Terence MacSwiney was holding a meeting of senior IRA officers in the Lord Mayor's chamber. Having completed their search, MacSwiney and eleven senior IRA officers were arrested by the soldiers and taken to Victoria Barracks for questioning. Among those arrested were Liam Lynch, Officer Commanding, Cork No. 2 Brigade and Seán O’Hegarty the second-in-command of Cork No. 1 Brigade.

Upon arrival at the barracks, the prisoners were divested of all their possessions. MacSwiney, however, steadfastly refused to part with one item – his chain of office. Later, in what can only be described as one of the greatest intelligence failures of the war, the British decided to release the eleven senior IRA officers. However, because he was found in possession of an RIC cipher and documents relating to Dáil Éireann, MacSwiney was charged with sedition and remanded in custody. In protest to his arrest, he decided to join the hunger strike that republican prisoners in Cork Prison had commenced the previous day.

On 16 August, MacSwiney was brought before a British Army court-martial in Victoria Barracks. Asked if he would be represented by counsel, he stated that the court was illegal. He went on to take sole responsibility for his actions and concluded, ‘This is my position, I ask for no mercy.’ The court found MacSwiney guilty. When the verdict was delivered, he declared, ‘I will put a limit to any term of imprisonment you may impose’, and, since he had been refusing food, he said he would be ‘free, alive or dead, within a month’. Terence MacSwiney was then sentenced to two years’ imprisonment which would be served in Brixton Prison.

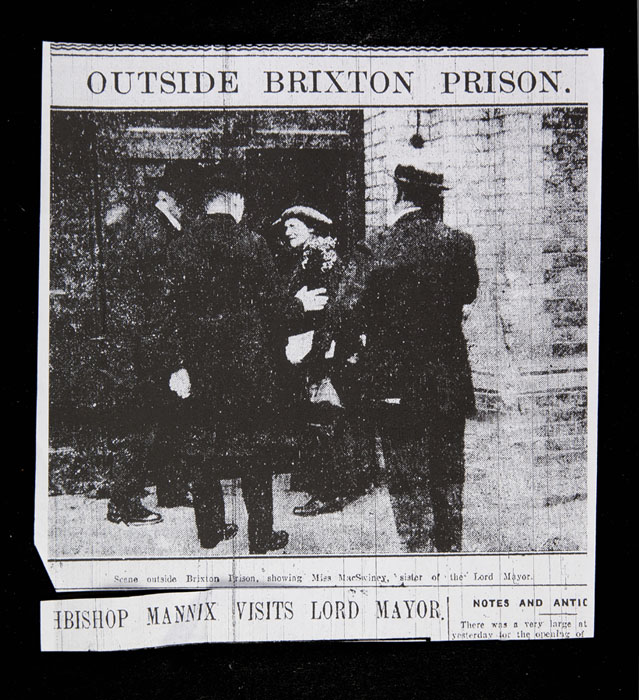

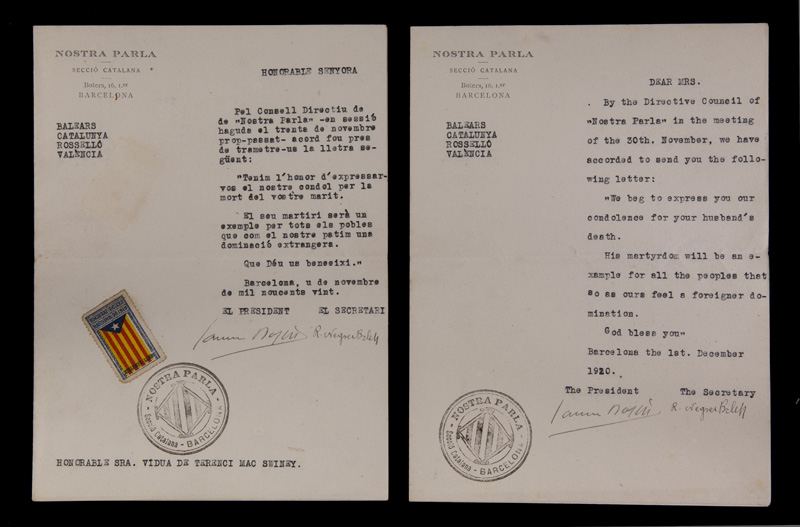

During the month of October 1920, Terence MacSwiney continued his hunger strike when he arrived at Brixton Prison. Within a short time, his health began to deteriorate. The media soon became focused on his ordeal and newspapers and journals throughout the world carried daily reports of his condition. Public meetings were held in France and Germany in protest against his imprisonment and other countries appealed for his release. MacSwiney’s hunger strike also drew attention to the fight for an independent Irish republic that was then taking place in Ireland.

As his condition faded, the prison authorities tried to give MacSwiney nourishment to keep him alive. His suffering is illustrated by this extract from a diary that his sister Annie kept at the time:

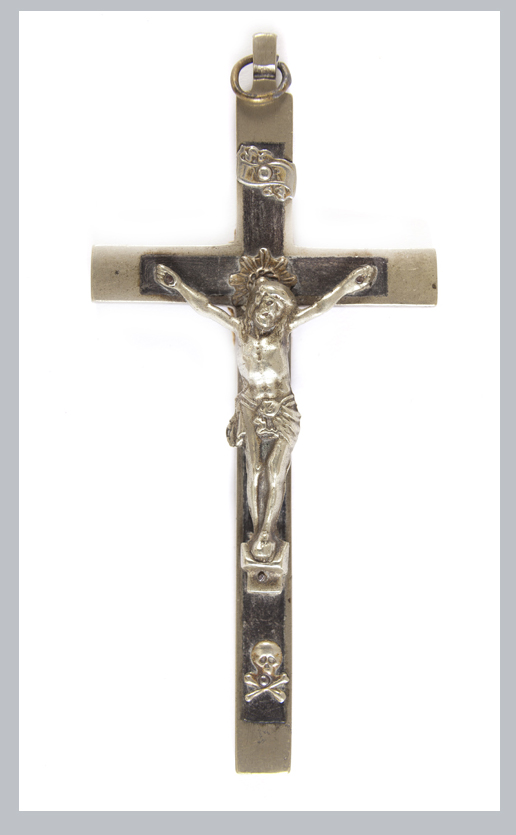

Throughout his hunger strike, Terence MacSwiney was sustained by his deep Christian faith and his belief in the cause of Irish freedom.

Diary-of-Terence-MacSwineys-Final-Days-at-Brixton-Prison-by-Anne-MacSwiney.pdf (size 8.5 MB)

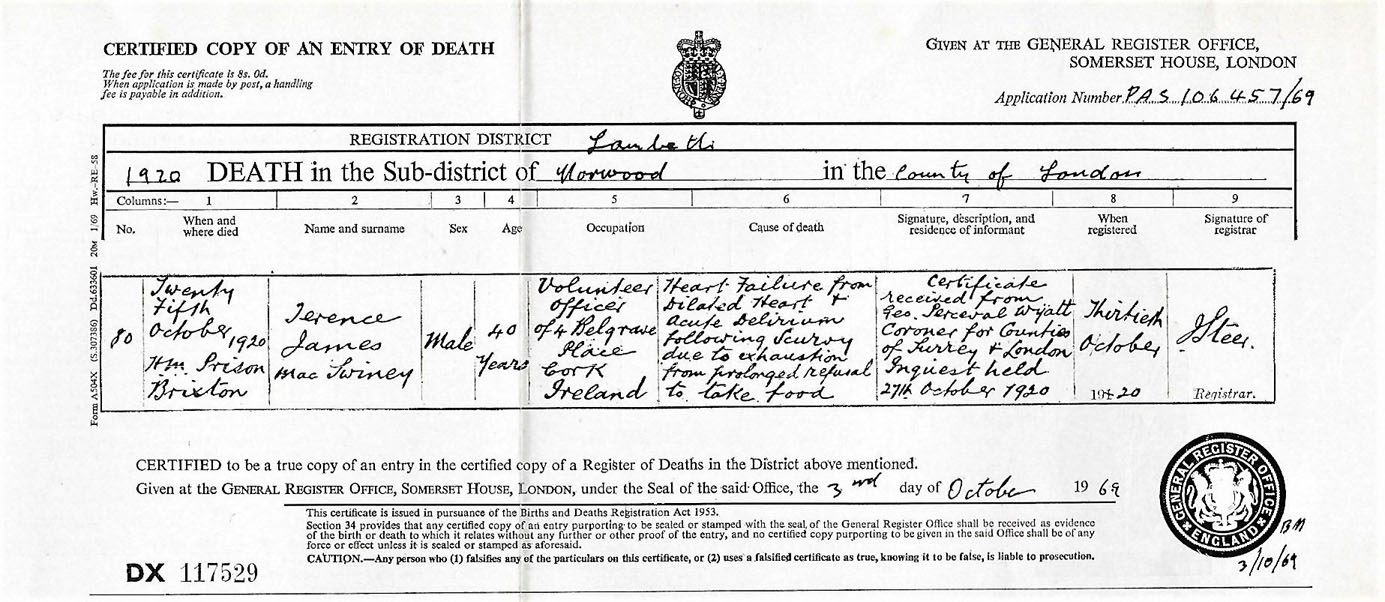

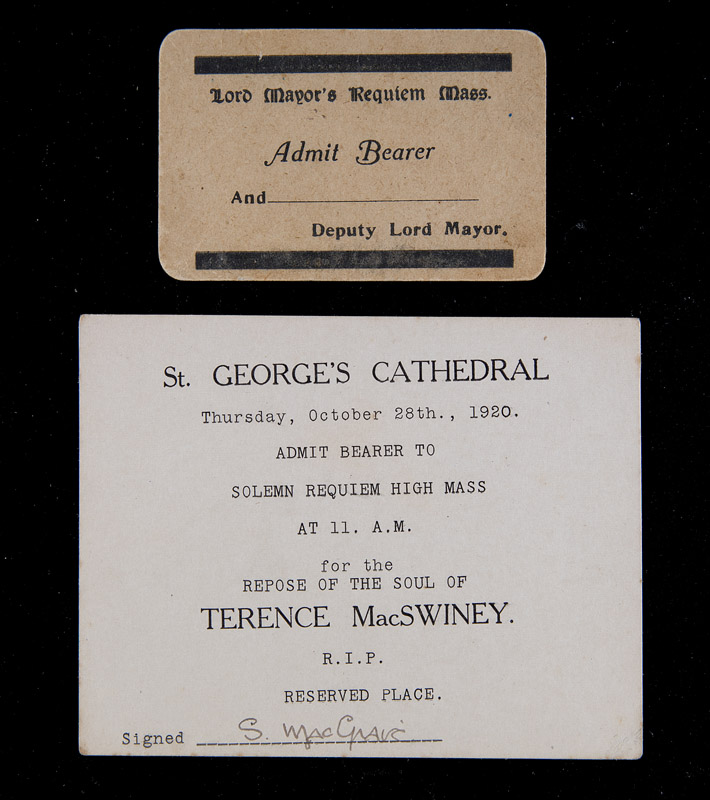

During the month of October 1920, Terence MacSwiney continued his hunger strike and his health deteriorated significantly. He sensed that the end was near and wrote last letters to the members of Cork Corporation, the Acting Lord Mayor of Cork, Councillor Donal Óg O’Callaghan, his constituents and members of the republican movement. During his last days, his chaplain, Fr. Dominic O’Connor, and members of his family spent many hours at MacSwiney’s bedside. Finally, at 5:40am on 25 October, he passed away on the seventy-fourth day of his hunger strike.

On 27 October, an inquest was held in Brixton Prison into the circumstances of MacSwiney’s death. The verdict was, ‘Death from heart failure following on scurvy and persistent fasting - refusal to take food’. After the inquest, the Home Secretary gave permission for the body to be removed from the prison. Thousands lined the streets of London when the remains were brought to Southwark Cathedral and they filed in to pay their respects. MacSwiney’s family wanted the remains to be taken to Dublin but the British Home Office ordered that they would be taken directly to Cork on board a government boat, the HMS Rathmore.

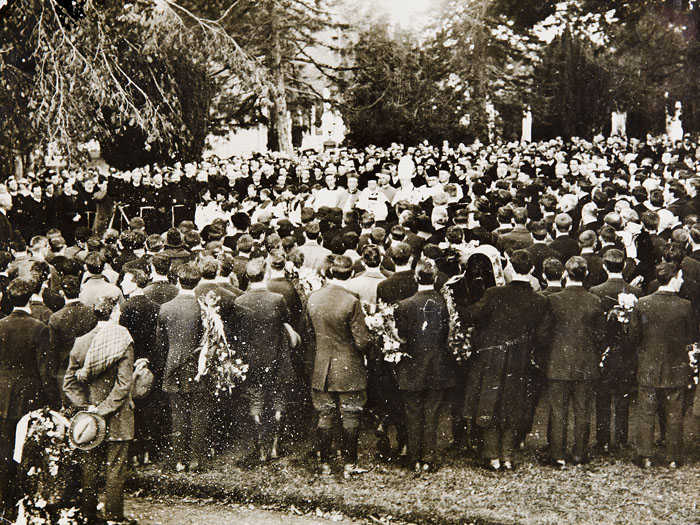

The Rathmore arrived in Cobh on the evening of 29 March. The remains were then transferred to a dockyard tug, the Mary Tavy, and taken upriver to Cork. Over 100 members of the Cork No. 1 Brigade of the IRA then escorted them from the dockside to the City Hall where they would lay in state. The following day, thousands of people filed past MacSwiney’s coffin in silent tribute. On 31 March, civil and religious dignitaries from all over Ireland joined MacSwiney’s family and the people of Cork in the Cathedral of Saint Mary and Saint Anne for the funeral Mass. After Mass, large crowds lined the streets of Cork as MacSwiney’s remains were taken to St. Finbarr’s Cemetery where they were buried in the Republican Plot alongside those of his friend and comrade, Tomás Mac Curtáin.

List-of-letters-of-sympathy-on-the-death-of-Terence-MacSwiney-01.pdf (size 17.5 MB)

List-of-letters-of-sympathy-on-the-death-of-Terence-MacSwiney-02.pdf (size 18 MB)

List-of-letters-of-sympathy-on-the-death-of-Terence-MacSwiney-03.pdf (size 20.7 MB)

The hunger strike can trace its origins to an ancient Irish tradition of shaming an enemy by publicly fasting in protest at their actions. It had a legal basis in the Brehon Laws where it was known as Troscadh or Cealachan. The practice was also used in ancient India and is mentioned in the Ramayana, one of the two major Sanskrit texts from that era. The Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi undertook long fasts during his campaign for Indian Independence.

Early in the 20th century, suffragist prisoners in Britain adopted the hunger strike. To prevent their deaths while in custody, a number of suffragettes were force-fed by the prison authorities. On Christmas Day 1910, Mary Clarke, the younger sister of the suffragette leader, Emmeline Pankhurst, died after being force-fed. Other prisoners who were force-fed suffered serious health problems. To counter adverse publicity caused by suffragette hunger strikers, the British Government passed the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913. This legislation, which became known as the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’, allowed striking prisoners to be released when they became ill, but, when they recovered, they were returned to prison to finish their sentence.

Following the 1916 Rising, Irish republican prisoners also adopted the hunger strike as a means of protest. On 20 September 1917, republican prisoners in Mountjoy Prison commenced a hunger strike to obtain political status. Five days later, Thomas Ashe, the President of the IRB, died after being force-fed. On 30 September, the strike was called off after British authorities introduced special rules for the treatment of republican prisoners. Another hunger strike by republicans in Mountjoy Prison, Dublin, in April 1920 led to them first being granted political status and then released. In all, approximately 1,000 hunger strikes took place between 1913 and 1922 involving about 10,000 people, with at least seven people dying as a direct result, and more from health complications later on.

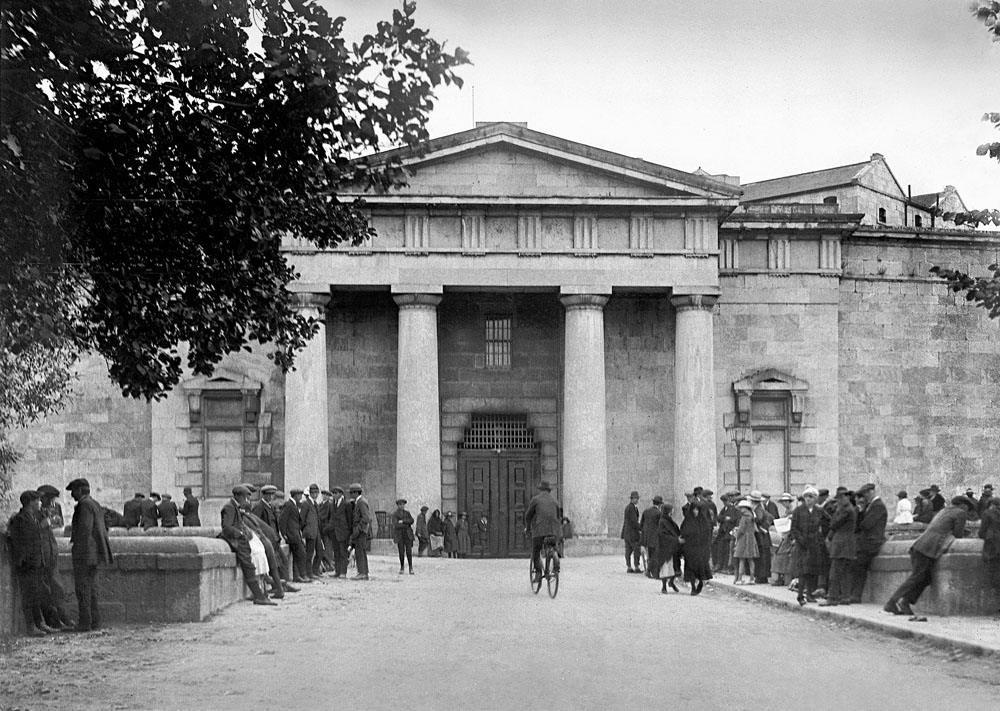

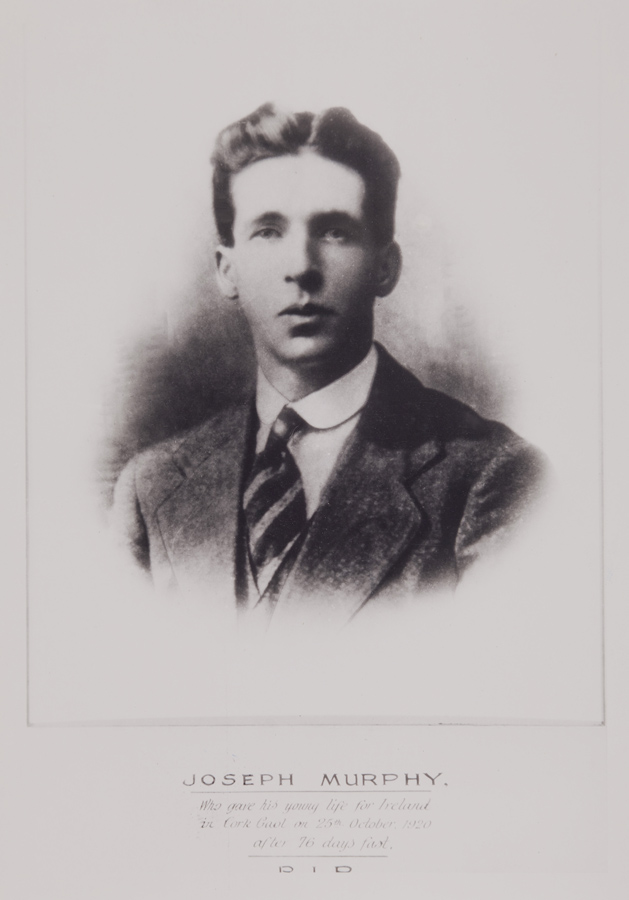

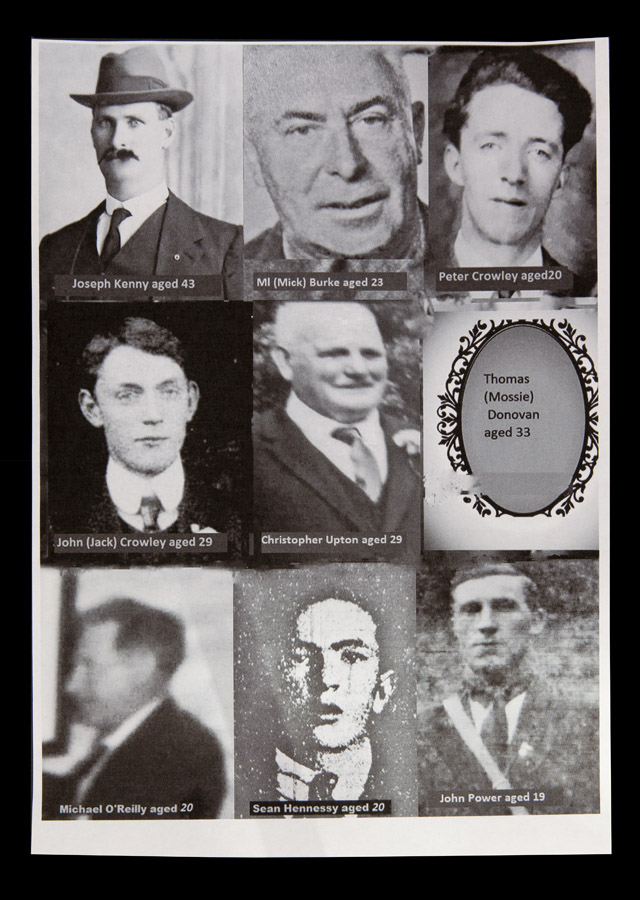

In the summer of 1920, the IRA campaign against the forces of the Crown intensified. In response, the attitude of British authorities towards republican prisoners hardened. On 11 August 1920, sixty-five republican prisoners in Cork Prison, most of whom were being held without trial, commenced a hunger strike demanding to be released. Terence MacSwiney joined the strike following his arrest at Cork City Hall on 12 August. MacSwiney was moved to Brixton Prison after his court-martial on 16 August. In the weeks that followed, the authorities released or transferred most of the striking prisoners in Cork until only eleven remained: Michael Burke, John Crowley, Peter Crowley, Thomas Donovan, Michael Fitzgerald, John Hennessy, Joseph Kenny, Joseph Murphy, John Power, Michael O’Reilly and Christopher Upton.

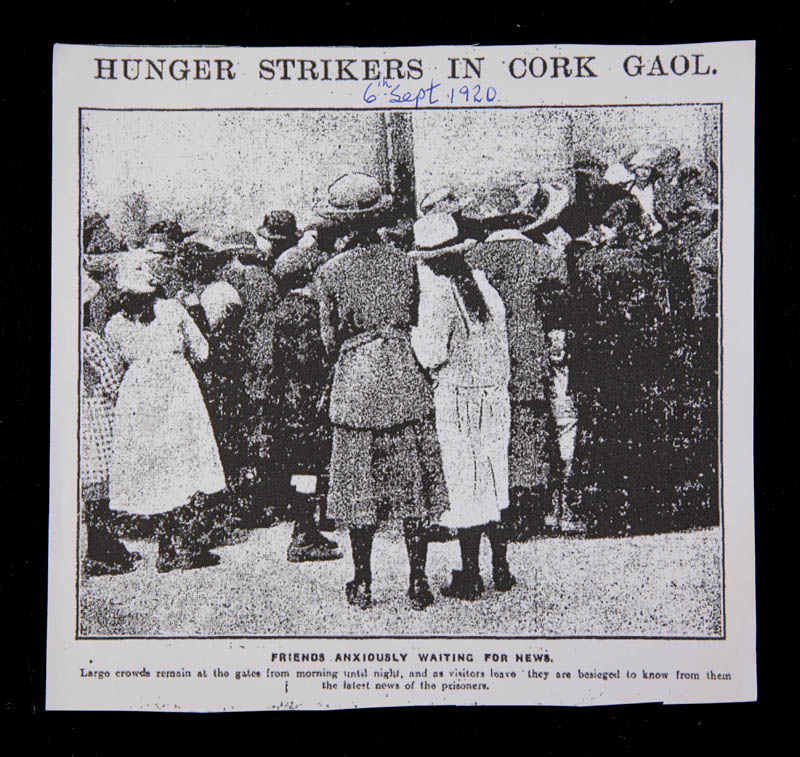

Each day, large crowds gathered at Gaol Cross to sing hymns and pray for the hunger strikers. While they were healthy enough to do so, the prisoners stood at the windows of the prison hospital and communicated with IRA signallers in the crowd using towels, pillow cases and lights to send messages in semaphore and Morse code. The signallers replied using similar means. On 7 October, Terence MacSwiney sent a message of support to the prisoners from Brixton on the fifty-seventh day of their strike. The following day the prisoners replied to MacSwiney.

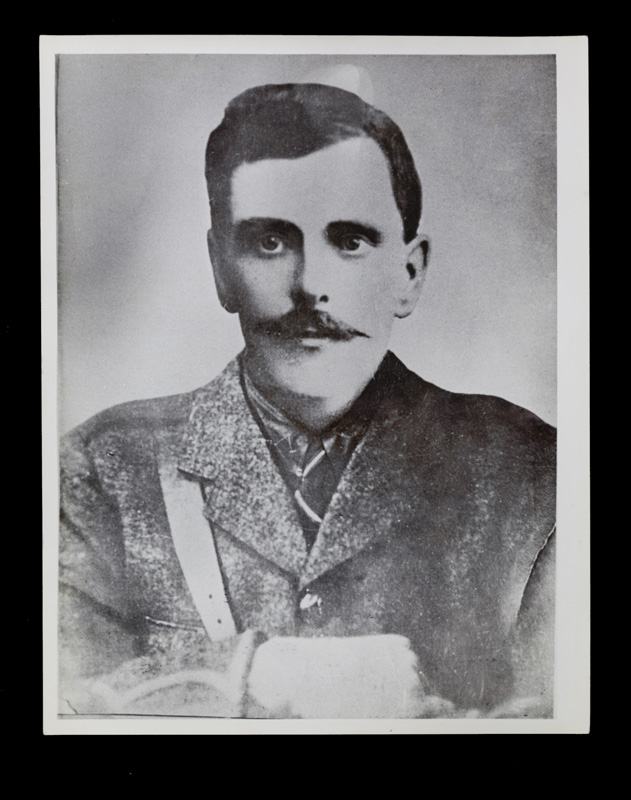

On 17 October, Michael Fitzgerald, the Commanding Officer of the 1st Battalion, Cork No. 2 Brigade, IRA, died on the sixty-seventh day of his hunger strike. On 25 October, Volunteer Joseph Murphy of the 2nd Battalion, Cork No. 1 Brigade, died after fasting for seventy-six days. That same day, Terence MacSwiney passed away on the seventy-fourth day of his fast. On 12 November 1920, Arthur Griffith, the acting president of the Irish Republic, advised the remaining nine prisoners to end their hunger strike and they agreed.

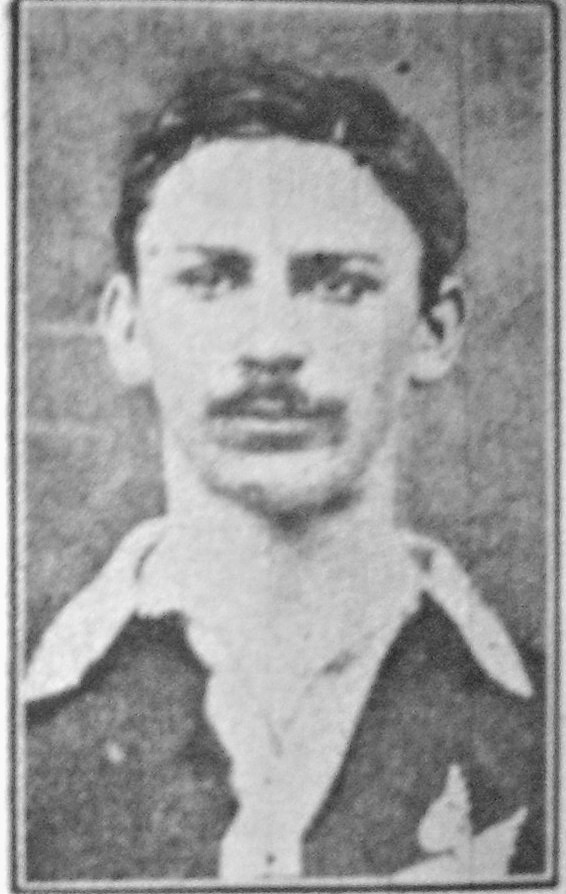

Michael Fitzgerald was born at Ballyoran, Fermoy, Co. Cork, in December 1881. He was educated at the Christian Brothers School in Fermoy and later found employment as a mill worker in the locality. He was the secretary of the local branch of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union and, in March 1914, he joined the Irish Volunteers. He proved to be an efficient officer and, in 1918, he was appointed Officer Commanding, 1st Battalion, Cork No. 2 Brigade.

On Easter Sunday, 20 April 1920, Fitzgerald led a successful raid on Araglin, RIC Barracks. Following the raid, he was arrested and sentenced to three months imprisonment at Cork Prison. Released in August 1919, he immediately resumed his activities with the Volunteers. On Sunday, 7 September 1919, he took part in the attack on a party of armed British soldiers outside the Wesleyan Church in Fermoy. One soldier was killed in this incident but all the weapons were captured. In the aftermath of this attack, Fitzgerald was arrested and incarcerated in Cork Prison.

Despite the threat of heavy penalties, no jury could be found to try Fitzgerald and other republican prisoners in Cork Prison. On 11 August 1920, he was among the prisoners who commenced a hunger strike demanding their release. Many were subsequently released or transferred until only Fitzgerald and ten others remained in Cork Prison. On 17 October 1920, Michael Fitzgerald passed away on the sixty-seventh day of his fast. His remains were taken to the Church of S.S. Peter and Paul in Cork on 19 October. During the service, British troops entered the church with a notice for the parish priest stating that no more than 100 people would be permitted to walk in the funeral procession. Notwithstanding this order, thousands took part when the remains were taken to Kilcrumper Cemetery outside Fermoy for burial.

Michael Burke: Twenty-three years old and from Folkstown, Thurles, Co. Tipperary. He was arrested in August 1920 at the home of a friend in Moyglass, Co. Tipperary. He was originally detained in Tipperary Military Barracks, then moved to Cork Military Hospital where he was treated for injuries. When he recovered, he was moved to Cork Prison.

John Crowley: Twenty-seven years old and a well-known footballer who represented Limerick at senior level. On 16 July 1920, he was arrested during a military roundup in the village of Ballylanders, Co. Limerick, along with his father and brothers, Michael and Peter. His father was released but the brothers were taken to Cork Prison. Michael was subsequently deported.

Peter Crowley: Eighteen years of age, he was also arrested during a military roundup in the village of Ballylanders in July 1920. He was the brother of fellow hunger striker, John Crowley.

Thomas Donovan: A native of Emly, Co. Tipperary, he was arrested at his parents’ farm, on suspicion of taking part in an attack on Ballylanders RIC Barracks and, taken to Cork Prison.

John Hennessy: Nineteen years old and a native of Limerick City. Well known in Irish cultural circles; he also taught Irish classes in Limerick Technical College. He was arrested while attending a summer session at Ballingeary Irish College.

Joseph Kenny: A resident of Grenagh, Co. Cork, and married with seven children; he had lived for several years in Montana, USA. He was working as a carpenter at the time of his arrest and was reported to be in delicate health.

John Power: Nineteen years old and a native of Cashel, Co. Tipperary. Early in August, he was arrested in the village of Rosegreen, Co. Tipperary, together with Joseph Delaney and Patrick Morrissey, and detained in Cork Prison. Both Delaney and Morrisey were subsequently deported.

Michael O’Reilly: A well-known athlete and Gaelic footballer; he was arrested on 16 July 1920 during a military round- up in the village of Ballylanders, Co. Limerick.

Christopher Upton: Twenty-seven years old, arrested on 16 July 1920 during a military roundup in the village of Ballylanders, Co. Limerick. Detained first in Bruff, then in Limerick; he was subsequently moved to Cork Prison.

During the War of Independence, the British Government frequently employed the provisions of the 1913 Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act, commonly known as the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’.

This Act was passed in Parliament in 1913 by the Liberal government of Herbert Asquith in response to the adverse publicity generated by the force feeding of women suffragettes who were on hunger strike in Britain. It provided for the release on licence of prisoners who were so weakened by their hunger strike that they were at risk of death. They had a predetermined period of time for their health to improve after which they were rearrested and returned to prison to serve the remainder of their sentence.

The nickname ‘Cat and Mouse Act’ referred to the way the government seemed to play with prisoners as a cat might play with a captured mouse. It soon proved counterproductive as repeated releases and re-imprisonments turned the suffragettes from targets of scorn to objects of sympathy.

Many Irish republican prisoners who were released under the provisions of the Cat and Mouse Act went ‘on the run’ to avoid rearrest and resumed their military activities.

Terence MacSwiney sent the following message of support on the 7th Oct 1920 to the eleven republican prisoners on hunger strike in Cork Prison:

On 8 October 1920, the eleven hunger-striking republican prisoners in Cork Prison sent the following reply to Terence MacSwiney:

The deaths of Tomás Mac Curtáin and Terence MacSwiney were a huge loss to their families, the republican movement and the people of Cork. Four months after Mac Curtáin’s death, his wife Éilís gave birth to stillborn twin girls. She subsequently contracted tuberculosis and moved to Switzerland with most of her children to recover her health. The family returned to Cork after seven years and her son, Tomás Óg, went on to become a member of the IRA Executive. After her husband’s death, Muriel MacSwiney travelled to America and gave evidence to the American Commission on Conditions in Ireland. She subsequently moved to Germany and then to France. Her daughter, Máire, would marry the son of Cathal Brugha.

Following the death of MacSwiney, Séan O’Hegarty took over command of Cork No.1 Brigade of the IRA. Born in Cork in 1881, O’Hegarty was a member of the Gaelic League, Sinn Féin and the IRB. He was also a founding member of the Irish Volunteers and would prove to be an aggressive commander who would wage a ruthless campaign against the forces of the Crown and their supporters.

On 4 November 1920, Donal O’Callaghan was elected Lord Mayor of Cork. Born in Cork in 1892, he was also a member of Sinn Féin and a founding member of the Irish Volunteers. A short time before his election, he received a threatening letter and he would spend much of his term of office on the run. He also travelled to America as a stowaway and would give evidence to the American Commission on Conditions in Ireland.

Although Tomás Mac Curtáin and Terence MacSwiney had ‘suffered the most’, their sacrifice would not be in vain. Their deaths inspired their comrades in the republican movement to continue the fight for an Irish Republic. The memory of their service and suffering would also help the people of Cork face the trials and tribulations that lay ahead.