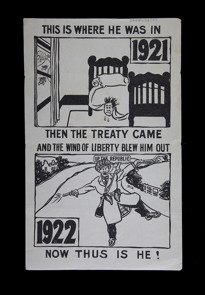

From Truce to Treaty

(Above) Treaty Negotiation Group London 1921 . 'Photo taken this morning in the Grosvenor Hotel'

Front row: Mr DeValera, Arthur Griffith

Middle row: Count Plunkett, The Lord Mayor of Dublin, Miss O'Brennan, Mrs Farnan and Miss O'Connor

Back row: Mr Childers, Dr Farnan and Mr R. Barton. 13/7/21

On 11 July 1921, a Truce came into effect ending hostilities in the Irish War of Independence. The following day, Éamon de Valera, the leader of Ireland’s republican movement, travelled to London at the invitation of British Prime Minister Lloyd George to explore the possibility of finding a settlement to the ‘Irish question’. De Valera and Lloyd George met four times that month but failed to reach an agreement. On 29 September 1921, Lloyd George again wrote to de Valera inviting Irish delegates to a conference in London in October with a view to ‘ascertaining how the association of Ireland with … the British Empire may best be reconciled with Irish national aspirations.’

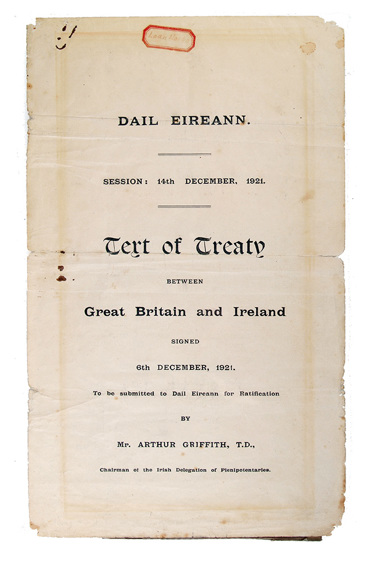

De Valera chose not to attend. Instead, Dáil Éireann appointed the following members to act as its plenipotentiaries: Arthur Griffith, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Michael Collins, Minister for Finance, Robert C. Barton, Minister for Economic Affairs, Edmund J. Duggan and George Gavan Duffy. Negotiations with a British delegation led by Lloyd George commenced at No. 10 Downing Street on 24 October and ended in the early hours of 6 December 1921 when the delegates signed a document entitled, ‘Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland’. That Treaty provided for the creation of a twenty-six county Irish Free State that would have dominion status in the British Empire.

(Above Left) Certificate Of The Treaty Between Ireland Britain 1921

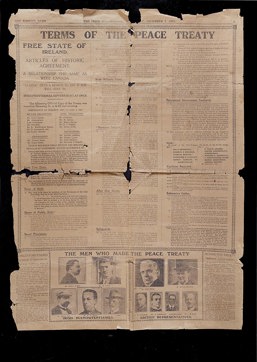

(Above Right) Newspaper Cutting Irish Independent, Terms of the Treaty 7th Dec. 1921. (Courtesy of the Irish Independent)

On 8 December 1921, the Irish cabinet decided by four votes to three to refer the Treaty to the Dáil for approval. On 14 December, the Dáil convened in the Council Chamber of University College Dublin, to debate the Treaty. Serious divisions quickly emerged and, as the days passed, the debate became increasingly bitter. Finally, on 7 January 1922, the Sinn Féin deputies in the Dáil voted sixty-four to fifty-seven to approve the Treaty.

Two days after Dáil Éireann approved the Anglo-Irish Treaty, Éamon de Valera resigned as President of the Irish Republic. His name was immediately put forward for re-election by deputies opposed to the Treaty, but the motion was defeated in the Dáil by sixty votes to fifty-eight.

On 10 January 1922, Arthur Griffith was nominated as President of Dáil Éireann. However, before the vote was taken, de Valera led the anti-Treaty deputies from the Dáil in protest at the election as president someone who he said would subvert the Republic. After de Valera and his supporters walked out, the sixty-one pro-Treaty deputies who remained, elected Arthur Griffith president. Following his election, Griffith appointed a new administration comprised of the following minsters: Michael Collins, Finance; George Gavan Duffy, Foreign Affairs; Eamonn Duggan, Home Affairs; William T. Cosgrave, Local Government; Kevin O’Higgins, Economic Affairs and Richard Mulcahy, Defence.

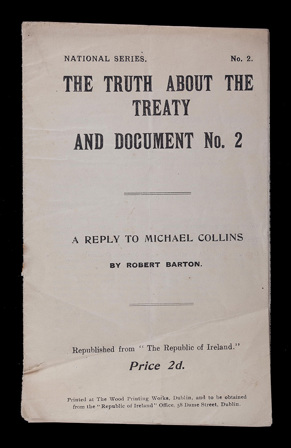

(Left) Booklet, 'The Truth about The Treaty, a reply to Michael Collins', written by Robert Barton 1921

(Left) Booklet, 'The Truth about The Treaty, a reply to Michael Collins', written by Robert Barton 1921

The once united group of Sinn Féin deputies in the Dáil were now deeply divided over the Treaty. Those who supported it were committed to establishing an Irish Free State, while its opponents, led by Éamon de Valera, would return to the Dáil, determined to undermine the Treaty and maintain the Irish Republic proclaimed in 1916 that they had taken an oath to defend.

As the British government did not recognise the Dáil, an Irish Provisional Government led by Michael Collins was formed on 14 January in accordance with the provisions of the Treaty. Most of its ministers held the same portfolio in the Dáil, and its function was to implement the provisions of the Treaty. Its term of office would expire on 6 December 1922 when the Irish Free State would formally come into existence. On the afternoon of 16 January, Michael Collins and members of the government took over Dublin Castle from Viscount FitzAlan, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. In the days that followed, it would focus on extending its authority to the rest of the country

The IRA Splits

The Anglo-Irish Treaty also caused divisions within the ranks of the IRA. While nine of the thirteen officers in its general headquarters supported it, approximately 75% of the 115,000 members it had in July 1921 were against it. This would cause difficulties when it came to taking over the barracks being evacuated by the British.

On 28 January 1922, the military barracks in Mallow became the first to be evacuated in Co. Cork. This barracks was occupied by anti-Treaty members of Cork No. 2 Brigade. On 31 January, Beggar’s Bush Barracks in Dublin was taken over by members of a pro-Treaty unit of the IRA known as the Dublin Guards that were clad in new green uniforms that had the same cap badge. Although other barracks were occupied without difficulties, in February, a tense stand-off developed in Limerick between pro and anti-Treaty in the city and it took the intervention of Minister for Defence Richard Mulcahy and Liam Lynch the commander of the anti-Treaty 1st Southern Division to defuse the situation.

(Above Left) Photo General Mulcahy Inspecting the National Army after evacuation of British Military Forces Collins Barracks 1922

(Above Right) Photo of Liam Lynch

The confrontation in Limerick led Arthur Griffith to ban an IRA convention planned for 26 March. Notwithstanding this, over 200 anti-Treaty officers gathered in Dublin on 26 March and reaffirmed their commitment to the Irish Republic, repudiated their allegiance to the Dáil and IRA general headquarters and placed the army under the control of its own executive. The IRA was now split. Members of organisation who opposed the Treaty retained the title Irish Republican Army, while those who supported it became known as the National Army.

(Above) Military coat Belonging to Major-General James Hogan Director of Intelligence, National Army.

On 29 March 1922, Volunteers from Cork No. 1 Brigade of the anti-Treaty IRA travelling on board a commandeered tugboat, intercepted British Admiralty ship Upnor off the coast of Cork. The ship was taken to Ballycotton, where the cargo of arms and ammunition it was taking back to Britain was removed. This incident outraged the British government who considered it to be a serious violation of the Truce. It also represented a direct challenge to the authority of Michael Collins and the Provisional Government with Winston Churchill stating that its control of Cork was ‘practically non-existent’. Tensions in Ireland increased dramatically on 14 April 1922, when 200 members of the IRA led by Rory O’Connor, occupied the Four Courts in Dublin and a number of other buildings in the city centre.

.

.

(Above Left) Photo of the S.S. Upnor

(Above Right) Dummy Artillery Shell Captured from the SS Upnor.

Ireland now seemed on the verge of Civil War. Such a prospect alarmed some senior IRA officers from both sides of the Treaty divide. On 1 May, ten of these officers, including Michael Collins, Liam Lynch, Seán O’Hegarty and Florence O’Donoghue, put their name to a list of proposals known as the ‘Army Document’ that were designed to maintain unity in the organisation. Two days later, O’Hegarty addressed the Dáil and urged it to accept these proposals as the best way to prevent civil war. Though the Dáil formed a committee to consider them, it failed to reach agreement.

The willingness to avoid conflict also led to a compromise whereby Hugh MacNeill, a representative of the Provisional Government would ‘officially’ take over Victoria Barracks in Cork when it was evacuated by the British on 18 May 1922, but it would then be handed over to Seán O’Hegarty and be garrisoned by members of Cork No. 1 Brigade. Notwithstanding these attempts to avoid violence, tension between supporters and opponents of the Treaty remained high as the country approached a general election that would decide the future of the Treaty and the Irish Free State.

(Left)Photo: The taking down of the Union Jack at Collins Barracks by British Troops.

(Left)Photo: The taking down of the Union Jack at Collins Barracks by British Troops.

On 19 May 1922, Dáil Éireann passed a resolution calling for a general election to be held in Southern Ireland on 16 June. On 27 May, the Provisional Government also issued an order authorising this election. It would be the first general election in Ireland held under the system of proportional representation. Unlike the one held in 1921, members of other parties and independents would stand. Those elected would form the Third Dáil.

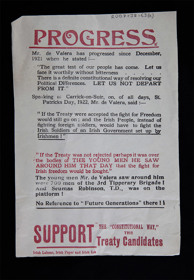

(Left and Right) Leaflets/Political Flyers: Pro-Treaty. Conlon Collection

(Left and Right) Leaflets/Political Flyers: Pro-Treaty. Conlon Collection

Both Éamon de Valera and Michael Collins were concerned that the election might deepen existing divisions. In an effort to prevent this, and to minimise Sinn Féin losing seats to other parties, they agreed an election pact on 20 May. Under this pact, an agreed panel of pro and anti-Treaty Sinn Féin candidates would be nominated that would reflect the current strength of each side in the Dáil. The Sinn Féin candidates elected would form a coalition government comprised of five pro-Treaty and four anti-Treaty ministers and the Dáil would elect the president. On 31 May, Winston Churchill, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, denounced the pact in the House of Commons, stating that it would ‘strike directly at the provisions of the Treaty’.

Prior to the election, Collins and a constitutional committee had spent months drafting a constitution for the Irish Free State that had to have the approval of the British Government. The text of this constitution, which required members of the Oireachtas (Legislature) to take an oath of allegiance to the Constitution of the Irish Free State and fidelity to the British monarch, was published on 15 June, the day before the election.

The result of the election was:

Pro-Treaty Sinn Féin: 58

Anti-Treaty Sinn Féin: 36

Labour Party: 17

Farmer’s Party: 7

Businessmen’s Party: 1

Independents: 9

The result was a decisive victory for parties and candidates that supported the Treaty.

On 22 June 1922, Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, a former Chief of the Imperial General Staff and Unionist MP for the constituency of South Down, was shot dead by two members of the IRA outside his home on Eaton Square, London. Wilson’s assailants, Commandant Reginald Dunne and Volunteer Joseph O’Sullivan were both members of the London IRA. Following the death of Wilson, British Prime Minister Lloyd George wrote to Michael Collins stating that evidence had been found connecting Dunne and O’Sullivan to the IRA. He also stated that the occupation of the Four Courts could not be allowed to continue. On 26 June, the situation worsened when the National Army arrested Leo Henderson a member of the Four Courts garrison who had commandeered a number of cars from a garage on Baggot Steet in Dublin. In response, members of the Four Courts garrison abducted the National Army’s Deputy Chief of Staff, General J. J. ‘Ginger’ O’Connell.

(Above) Rivet from Bridge Bullet Casing Bullet from Anti-Treaty Forces trying to blow up Parnell Bridge Aug 1922.

Following the killing of Wilson and the abduction of O’Connell, Michael Collins decided to act. On the evening of 27 June, Major General Emmet Dalton and Commandant General Tony Lawlor went to Marlborough Barracks in Dublin where the British Army gave them two 18 pounder field guns and ammunition. These guns were deployed across the River Liffey opposite the Four Courts. At the same time, the National Army took up positions around the buildings. At 4.20 a.m., after an ultimatum to surrender was ignored by the IRA, the guns opened fire on the Four Courts. This action marked the beginning of Ireland’s Civil War.

Outnumbered and outgunned, the Four Courts garrison surrendered on 30 June. The National Army also attacked IRA positions in the centre of Dublin and by 5 June, it had taken control of the city. After losing the Battle of Dublin, the IRA, led by Liam Lynch, would continue the fight against the forces of the Irish Free State from the south and west of the country.

On 12 August 1922, Arthur Griffith, the President of Dáil Éireann, died of a cerebral haemorrhage. His funeral took place on 17 August. By then, the National Army had taken control of most of the ‘Munster Republic’ and Michael Collins decided to embark on an inspection of the area. On the morning of 20 August, he left Portobello Barracks in Dublin for Cork accompanied by a military escort. He arrived in in the city that evening and stayed in the Imperial Hotel. The following day, Collins met with the editor of The Cork Examiner and with a number of city bankers. He also visited Cobh and Macroom.

At 6.15 a.m. on 22 August, Collins left the Imperial Hotel for West Cork. He was travelling in a Leyland Eight touring car with Major General Emmet Dalton. Accompanying them was the ‘Slievenamon’ Rolls Royce armoured car, a Crossley tender carrying riflemen and a motorcycle scout. At the same time, a group of IRA officers, including Liam Deasy and Tom Hales, were meeting in Bill Murray’s farm at Beal na mBlath. When Collins was recognised as his convoy passed through the area, a decision was taken to ambush it on its way back to Cork. Initially, a large ambush party was deployed, but that evening most were stood down leaving a small number to dismantle a mine that had been laid on the road. They were doing this when Collins’s convoy arrived. It was around 7.30 p.m. and a firefight developed that lasted around thirty minutes. As it was drawing to a close, a shot was fired that hit Collins in the head and killed him.

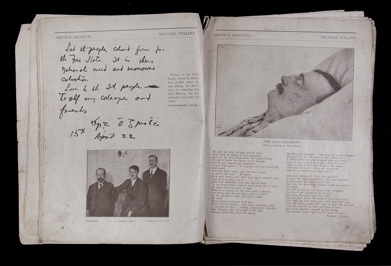

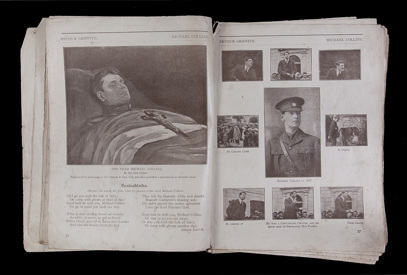

(Above, Left and Right) Booklet: Excerpts from a Booklet Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins-02

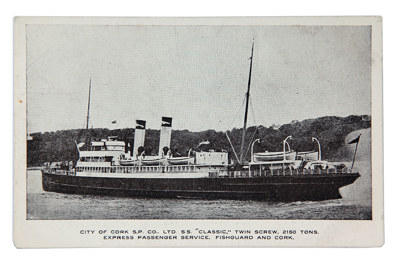

Michael Collins was the only fatality at Beal na mBlath. That night, his remains were taken to Shanakiel Hospital in Cork. The following day, members of the National Army escorted them through the city streets to Penrose Quay where they were put on board the SS Classic and taken to Dublin. His funeral took place on 28 August 1922.

.

.

(Above Left) Postcard: The S.S. Classic

(Above Right) Postcard: The memorial to General Michael Collins at Beal na Blath. Erected April 1925.

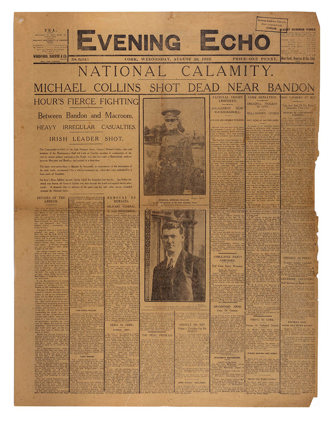

(Above Left) Photo: Michael Collins lies at Shanakiel Hospital After His Death

(Above Right) Newspaper:The Evening Echo carrying report of Michael Collins Death 1922.

On Sunday, 5 February 1922, the female republican organisation, Cumann na mBan, held a special convention in Dublin’s Mansion House to discuss the Anglo-Irish Treaty. An overwhelming majority of the delegates (419 to 63) voted in favour of a motion proposed by Mary MacSwiney, the Sinn Féin TD for Cork Borough, to reject it and reaffirm the organisation’s allegiance to the Irish Republic. A counter-proposal made by Jennie Wyse Power, a founding member of the organisation and its first president, that the organisation remain neutral was defeated.

In March 1922, Cumman na mBan formally split when Jennie Wyse Power and other pro-Treaty members established Cumann na Saoirse. In Cork, the majority of Cumann na mBan branches and the members of the District Council supported the Treaty. On 4 April 1922, the anti-Treaty Cumman na mBan Executive expelled prominent members of this group from the organisation and prohibited them from using its name. However, this order was ignored. The name was retained by Pro-Treaty members in Cork and they elected the renowned opera singer Birdie Conway as their president. During the Civil War, this group would support the National Army by organising dances, searching female prisoners and visiting hospitals to provide items such as cigarettes, fruit and playing cards to wounded soldiers.

(Above Left) Photo: Mary MacSwiney, returning from the USA

(Above Right) Photo: Cumann Na mBan group outside the Washington St Courthouse with President Cosgrave. (Mary Conlon Collection)

The republican members of Cumann na mBan adopted a more militant role in the conflict. They stored arms for the IRA, acted as couriers and nurses, took part in protests and marched in republican funerals. Around 560 members were imprisoned during the war. Among those incarcerated was Mary MacSwiney. However, on two occasions (November 1922 and April 1923) she embarked on a hunger strike that led to her release. Three members of the organisation, Mary Hartney, Lily Bennett and Margaret Dunne, were killed by the National Army during the war. Another, Annie Hogan, died after being released from prison following a hunger strike.

On 27 September 1922, with the IRA continuing its campaign of guerrilla warfare against the National Army, Dáil Éireann passed emergency legislation known as the Public Safety Bill. This bill authorised the National Army to establish Military Courts with powers to inflict a punishment of death or imprisonment on personnel found guilty of taking part in or aiding attack against the National Army; unlawfully destroying or damaging public or private property; being in unlawful possession or arms, ammunition or explosives or breaching a general order made by the Army Council. The first execution under the provisions of this legislation took place on 17 November 1922. By the end of that month, eight republicans, including the noted author Erskine Childers, had been executed.

(Above) Postcard: Photo of Male Prisoners in Cork Womens Gaol.

Liam Lynch, Chief of Staff of the IRA, responded to these executions by issuing an order on 30 November, which stated that all members of the ‘Provisional Parliament’ who voted for what he called the ‘Murder Bill’ and all officers of the ‘Free State Army’ who supported the bill or were active against the IRA were to be ‘shot at sight’. Eight days later, on 7 December, the IRA shot the pro-Treaty TDs Brigadier General Seán Hales and Pádraig Ó Máille, as they emerged from a hotel on Ormonde Quay in Dublin. Hales was killed and Ó Máille was wounded. At the time of his death, Sean Hales’ brother Tom was a senior officer in the IRA.

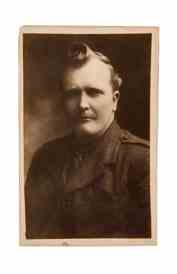

(Above) Photo: Sean Hales

(Above Right) Jacket/Coat that Sean Hales Civil was wearing when he was killed

The following day, in retaliation for the killing of Hales, the Provisional Government ordered the immediate execution without trial of the following senior IRA officers, one from each province, who were incarcerated in Mountjoy Prison in Dublin: Rory O’Connor, Richard Barrett, Joseph McKelvey and Liam Mellows. A total of eighty-one republican prisoners would be executed during the Civil War. Among that number was Volunteer William Healy, a member of Cork No 1 Brigade of the IRA. He was executed by the National Army in Cork Male Prison at 8 a.m. on 13 March 1923.

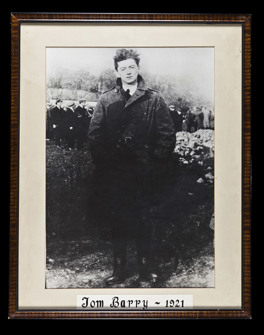

Though it had sustained a number of defeats and many of its members were in prison, as 1923 dawned, the IRA continued operations against the National Army. On 4 January, it demonstrated its military capability when sixty-five Volunteers led by Tom Barry attacked National Army positions in the town of Millstreet. Co. Cork, killing two soldiers and taking thirty-nine prisoners.

(Above) Photo Framed: Tom Barry. Michael O'Donnchu Collection

Notwithstanding operations such as this, the National Army had more men, more arms and better equipment. As the war continued, many senior IRA officers came to accept that a military victory was not possible. After he was captured on 18 January, Liam Deasy, the commander of the 1st Southern Division, signed an appeal calling on Éamon de Valera, Liam Lynch and members of the IRA Executive to surrender. Republican prisoners in Limerick and Clonmel also called for an end to the war and at a meeting of the IRA Executive held on 24 March, it emerged that some members were reluctant to continue the fight.

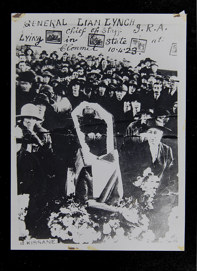

(Above) Photo: General Liam Lynch Lying in State, Clonmel 1923.

Despite these developments, the IRA Chief of Staff, Liam Lynch, still believed victory was possible and he dismissed all suggestions of a ceasefire. On 10 April, he was attending a meeting of the IRA Executive near Goatenbridge, Co. Tipperary, at the foot of the Knockmealdown Mountains when scouts noticed a large National Army force approaching. On hearing this, the members of the Executive attempted to escape up the mountains. As they did so, shots were fired and Lynch was seriously wounded and captured. He was taken to Clonmel by ambulance and died later that evening. After Lynch’s death, the republican resolve to continue the war collapsed. On 24 May, Frank Aiken, his successor as Chief of Staff, ordered the IRA to dump its arms. That same day, Éamon de Valera issued a statement to the ‘Soldiers of the Republic and Legion of the Rearguard’ which said, ‘Military victory must be allowed to rest for the moment with those who have destroyed the Republic’. Ireland’s Civil War was over.

The decision of the IRA leadership to end the Civil War marked the close of one of the most tragic chapters in the history of Ireland. The conflict lasted ten months, three weeks and five days. It is estimated that between 1,500 and 1,700 people lost their lives, thousands more were injured and approximately £50,000 worth of damage had been done.

The Civil War would also shape Ireland’s political landscape for decades. On 27 April 1923, pro-Treaty TDs and their supporters formed the Cumann na nGaedheal party. Led by William T. Cosgrave, it would be the party of government until 1932. In September 1933, it merged with the National Centre Party and the National Guard (Blueshirts) to form the Fine Gael party. After the war, Sinn Féin refused to recognise the Free State or take its seats in the Dáil. By 1926, its president, Éamon de Valera, was in favour of abandoning the party’s policy of abstentionism. After the party reaffirmed the policy by a vote of 223 to 218 during its annual Ard Fheis on 10 March 1926, de Valera resigned as president. On 16 May 1926, he and his supporters formed the Fianna Fáil party. The party won 44 seats in the general election held in June 1927 and its TDs took their seats in the Dáil on 12 August. It went on form a government after the June 1932 general election.

(Above) Lapel Badge: Blueshirts, Fine Gael 1933. Tom O'Neill Collection.

(Above Right) Lapel Badge: Army Comrades Association Blueshirts Fine Gael.Tom O'Neill Collection

Many members of the IRA emigrated after the Civil War. Others supported Fianna Fáil while the more militant members remained committed to establishing a thirty-two county Irish Republic by force of arms. The strength of the National Army stood at 55,000 at the end of the war. The government decision to reduce its strength to 18,000 was one of the factors that led to the Army Mutiny of March 1924. On 1 October of that year, the title ‘National Army’ would pass into history when the Irish Defence Forces were formally established by the Free State Government.

With thanks to the following