Our Collections: Aspects of Life in Medieval Cork

Copper engraved print of Cork by Daniel Meisner c.1638.

From the Sciographia Cosmica published by Paulus Furst between 1637-78

Games and Pastimes of the Ages

by Emmanuel Alden

Throughout history, people around the world have turned to games, sports, and other pastimes for entertainment to while away their free time. In Cork, games of skill and of chance have always played a role in people’s daily lives. With each new group of people who invaded the region, and with new discoveries, the choice of games and pastimes changed. Nevertheless, the artifacts held at the Cork City Museum provide a vital link with the past and reveal some of the activities which residents of Cork in ages past used for entertainment.

Selection of gaming and musical instrument objects found at the South Main Street and Christ Church sites in Cork City

Gaming Pieces in ivory, bone, and wood.

. .

Many varying styles of board games were played in the past, which required an equally wide variety of gaming pieces. They ranged from pegged pieces, which were stuck into the board, to simple two-sided chips or tokens with or without holes in the middle as well as hand-carved chess pieces. Several of these small artefacts have been found during excavations of Cork’s medieval city centre. These pieces were made from different materials and the surviving examples were crafted from wood, bone, ivory and antler. Sixteen bone or antler gaming pieces, along with four wooden pieces, were found at the site of Christ’s Church.

Gaming pieces. Anglo-Norman type

Detail photos of bone made gaming piece below

Detail photo of wooden made gaming piece below

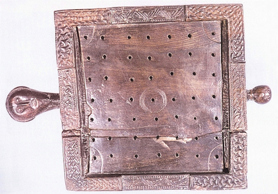

The oldest gaming pieces recovered consist of two wooden and three bone pieces dated to the Viking age. These game pieces are tall figures of varying shapes; the bone pieces have flat bottoms and are similar in shape to onion bulbs. The two wooden pieces are also varied in shape, one like the bone pieces, while another one loosely resembles a spruce tree, with three downward facing conical shapes stacked on top of each other. The latter piece has a peg, which allowed it to be placed into the holes on an early game board, such as the Hnefetafl board recovered from the Ballinderry Crannog.

The Hnefetafl Board recovered from the Ballinderry Crannog. Photo courtesy of the National Museum of Ireland

Most of the gaming pieces in the Museum are flat discs made from bone, they date to the later medieval period. These pieces are often decorated on one side and plain on the other; in addition, some of them may have been painted on one side. This would allow the two sides to be easily distinguished during gameplay. These pieces may have been used to play board games such as ‘9 Men’s Morris’ or ‘Tables’, an older version of draughts.

A few pieces came from medieval chess sets. These included three wooden pieces, two of which probably represented knights and one a pawn, and two bone pawns. The bone pawns bear geometric carvings, which may reflect the early origins of chess in the Islamic world.

Medieval gaming pieces. Hiberno-Norse type, Ivory (Walrus)/Antler/Wood found at the ChristChurch site

Detail of medieval gaming piece made from bone

Medieval gaming pieces. Hiberno-Norse type, Ivory (Walrus)/Antler/Wood found at the ChristChurch site

The four dice from Christ’s Church follow a 13th-14th century opposing numbers format, called ‘primes’, of 1/2, 3/4 and 5/6. One die from South Main Street followed the opposing numbers format, called ‘sevens’, common to both ancient Roman and modern dice, whereby each opposing number pair adds up to seven, as 1/6, 2/5 and 3/4. Due to its excavation location, this die cannot be precisely dated, however, it is unlikely to be from the same era as the other dice.

Five dice: Four Bone Dice. Found in Christ’s Church, Cork Site and an Antler or Bone Die Found in South Main Street, Cork Site.

Wooden dice detail below

The sizes of four of the dice are nearly identical, but one die from the Christ’s Church site is significantly larger. All of these dice are highly irregular in shape, where one opposing pair of sides is much larger than the others. Among the dice from Christ’s Church, in three examples the sides 1/2 are largest, and thus the most likely to land up. In the fourth example, the sides 3/4 are most likely to be landed on. In the die from the South Main Street, the sides 1/6 are most likely to land face-up. Testing was done with one example, which found the most probable two numbers on that die had an 85% likelihood, or roughly five out of six throws, to land upward.

The irregular shape of these dice may have been caused by imperfect craftsmanship, or may have been an attempt at crooked dice, used to cheat at games. While it is difficult to prove that any crooked die was intentionally made for cheating, dishonesty was a significant problem in medieval dice games, so much so that laws were made with harsh punishments for those caught cheating. Indeed, cheating was so common that literary sources sometimes used names to differentiate between types of crooked dice, including the terms ‘flat’ and ‘barred’ to describe them. In addition to gambling, dice were also frequently used in the late medieval world as part board games such as tables.

A child’s toy Viking long ship fragment, Wooden Artefact, Christ’s Church Site.

The board game ‘9 Men’s Morris’ was probably introduced to Cork by the Anglo-Normans following their invasion of Ireland. It is possible that some of the flat gaming pieces found in Cork were intended for use in this game. This particular board was inscribed onto a wooden cask-head, and a separate stone board was also recovered from the Christ’s Church site as well. While these boards were very simple,other gaming boards were far more elaborate, made of precious materials and worthy of royalty.

In addition to games, toys and sports were also enjoyed by the medieval population of Cork. Although Cork’s earliest roots stemmed from St Finbarr’s monastic settlement, the city itself was established by Vikings. With a rich history relating to the Vikings, the long ship was an important symbol of their past. A fragment of a toy long ship was found at the Christ’s Church site, with parallel examples found in Scandinavia and medieval Dublin, the most significant of the Irish Viking cities.

Wooden Bowling Ball. This wooden lathe-turned ball was found at Christ Church, Cork. It is made from the wood Lignum Vitae or 'Wood of life', so-called because of its density and durability, which was imported from the West Indies or Tropical America. Bowls was a popular ball game in 17th century Cork, indicated by at least two known bowling greens on the present sites of the English Market and the Lee Maltings

Included below are the bowling ball with wooden spoons and a bowl found at the Christ Church sites. These objects and more are all on public display at Cork Public Museum.

At the opposite end of the medieval world, after the Americas had been opened to European trade, rare and valuable resources reached Cork. The ‘wood of life’, lignum vitae, was imported from the West Indies to the city, where some of it was used to produce lathe-turned bowling balls in the 17th and 18th centuries. As a strong, high density wood, this material was especially suited for this purpose. Multiple bowling balls have survived from the early-modern era in Cork, including one from the Christ’s Church site.

Further Reading:

Carter, J. M., Medieval Games, Sports and Recreation in Feudal Society,Greenwood Press, 1992.

A small selection of medieval objects on display at Cork Public Museum

Music in Medieval Cork

by David O’Mahony

In the 12th century, Gerald of Wales wrote the Topography of Ireland, an outsider’s account of the land and its people. In this work he commented on the musicians of the island, whose compositional skills and distinct melodies were of great standing. The virtuosos, who impressed Gerald with their fast playing may have been unique to Ireland, however continental cultures also impacted on music in Ireland following the coming of the Normans. The artefacts held in Cork Public Museum, found at the South Main Street site, are an important witness to musical traditions at a time that had no audio recordings. These artefacts allow us to gain a better understanding of human artistic expression. Music is played every day all around us, and by understanding the time, place, and people behind the music of medieval Ireland, we can more fully relate to the Irish past.

Multiple tuning pegs from the mid- to late-13th century made of bone. Other pegs made of yew date to the mid-12th century, all found on South Main Street, Cork.

Detail below of wooden tuning peg. All these tuning pegs are on public display at Cork Public Museum.

The first items, that resemble drum beaters, are tuning pegs for stringed instruments. Two sets of tuning pegs are held in the Museum, both of which were very likely to be for psaltery instruments. Dating to the 12th and 13th century respectively, we can assume, the two pegs belonged to either a lute (resembling a modern guitar) or a fiddle. These were unlikely to be for a lyre, as these instruments had fallen out of fashion by the 12th century. However, the Irish were known to have an instrument similar to a lyre and called a timpan, which was plucked when played. These pegs may seem like simple objects to produce, yet precision was important when keeping instruments in tune. Unlike modern instruments, medieval pegs were used with a tuning wrench, as suggested by marks at the top of the pegs.

We can assume that these artefacts were part of an instrument that was played at taverns, markets, or public events. The lute or fiddle did not have as high a standing as the harp. This standing is comparable to the position of the nomadic jongleur of Europe, who was regarded as a rank below the court minstrel, a well-esteemed musician who performed for nobility. In the instance of the items found at the Christ’s Church site in Cork, it is believed that these instruments belonged to a crossan, who was a travelling entertainer or musician. Harpers of the early medieval period were regarded as being of a higher ranking than other musicians in Gaelic society, usually serving under a chieftain. According to the Brehon Laws, these Irish string players, called cruitire, often received compensation for any harm done unto them and players whose fingernails had been damaged sometimes received payment and a ‘wing nail’ was provided to allow them to play.

The Anglo-Norman invasion, backed by Pope Adrian IV, greatly transformed Irish society, and caused the Brehon Laws to decline. The Pope sought to further bring the Church in Ireland under the influence of Rome. With these changes, music became exclusive to religious practices, a process similar to that experienced by Anglo-Saxon music. This change caused a split between liturgical and secular music, with the harp becoming an ecclesiastical instrument.

A bone bridge for a stringed instrument, dated to the 12th or 13th century, found on South Main Street, Cork.

At the same site, a late 12th to early 13th century bridge belonging to either a fiddle or a lute, was found. This bridge is an anvil-shaped device that was used to support the strings and allow them to vibrate and was usually located at the plucking or bowing end of an instrument. In this case, the bridge was designed to accommodate seven strings and is made from bone material. There is some ambiguity between the parts of fiddles, lutes, and even timpan instruments. The timpan was plucked before the 12th century, and later was played with a bow.

There is an abundance of sources, both textual and visual, that suggest the use of six- to eight-string instruments during devotional practices. Gerald of Wales mentioned in the Topography that holy men carried instruments and found ‘pious delight’ while playing them. It is probable that this bone bridge was part of an instrument used in religious services - one that accompanied liturgical services and provided a medieval equivalent to a ‘backing track’ in one of the churches in Cork City, possibly in Christ’s Church itself.

Whistles and a ‘buzz bone’ found on South Main Street, Cork.

Detail of whistle made from bone below. All these objects and more are on public display at Cork Public Museum

Cork Public Museum also houses a selection of medieval wind instruments that were common across early medieval Europe. These artefacts are made from the long ulna bones of large birds, typically swans or geese. While dating of these specific items is difficult, it can be assumed that they were from the same period as the tuning pegs found at Christ’s Church. The bone whistle is a primitive instrument, a basic woodwind instrument that contains a D-shaped hole for the voicing of the notes, and between two to six holes for the fingers of a player. This early design resembled a modern-day tin whistle. Known as a buinne or fedan in Ireland, this instrument type can go back as early as the 9th century. The artefacts on display are either damaged or represent the pieces that were not fit for use and discarded.

We can associate these whistles with a travelling musician, who likely carried a bone flute as it required little to no maintenance, unlike harps or lutes. As the Anglo-Norman invaders also used a similar instrument, it is not exclusive to Ireland. However, texts reveal that the Irish approach to music relied heavily on improvisation and skill over knowledge of any tunes. Yet, with the increasing importance of music in the liturgy, these instruments sometimes accompanied choir signing after the 13th century. It is possible that these whistles were used in Christ’s Church during liturgy, but they could have also been played on South Main Street, which was a hub of activity in Cork at the time.

Another instrument found with the music items is the so-called ‘buzz bone’, which was possibly a children’s toy; it consisted of the metapodial bone of a pig with a string threaded through its hole. When the thread was pulled, it created a buzzing noise. Although this small object was not a professional instrument, it certainly was a pleasing object from the medieval world.

Further Reading:

Buckley, A., ‘Music and Musicians in Medieval Irish Society’, in Early Music of Ireland, vol. 28, no. 2, Oxford University Press, 2000.

Grattan Flood, W.H., A History of Irish Music, Browne and Nolan Limited, 1913.

Williams, J.E., The Court Poet in Medieval Ireland, Proceedings of the British Academy, 1971.

Pieces of Piety in Medieval Cork

by Emmanuel Alden & David O’Mahony

A collection of religious artefacts held in Cork Public Museum provides deep insight into the medieval culture and ideas of salvation that can be glimpsed through objects associated with church architecture, burial, and pilgrimage. Items discovered at the site of St Mary’s of Isle, a location of the Dominican Order, also show the stonework methods used by monastic settlements in the city. Objects made of amber or porphyry, materials that are not native to Ireland, suggest links with European trade networks and crafting cultures, which impacted the island in the medieval era.

Artefacts from the Priory of St Mary’s of the Isle: stone architectural elements of the building, including the basal stone of a column, and a ‘voissour’, a fragment of an arch with a rosette, 14th or 15th century.

Just outside the southern walls of the medieval city of Cork, on what became known as ‘Abbey Island’, the Dominican Order of preaching friars established a monastery in the 13th century. The ground was boggy marshland, prone to flooding, and required extensive shoring and infill prior to the construction of the Dominican house. However, the priory was well positioned, directly between the ecclesiastical centre at St Fin Barre’s Cathedral and the South Gate Bridge entrance to the city.

Construction of the priory took place in stages, with the initial building being a simple east-west oriented one-aisle church, to which was added a single transept on the north side. Rooms, such as a refectory, a chapter room, a sacristy and dormitories were built around a central courtyard, in a manner reflecting other medieval monastic and mendicant houses. During extensive renovations on the priory in the late middle ages, a tower was added to the church, and a cloister was added within the courtyard. While much of the earlier construction of the building used a durable, easily worked stone imported from Dundry in England, later elements utilized limestone sourced from local quarries.

The base of a column, shown in the exhibition, is made of the Irish limestone and has the form of two octagonal pieces fused together on one side, creating a dumbbell shape. They served as the base of columns which supported the arcade of the cloister. In monastic buildings, the cloister served as the central hub of the monks’ or friars’ life, around which the activities of everyday work and religious practice took place.

The voussoir, decorated with a finely carved rosette and cut from Irish limestone, was a segment of an arch that was probably positioned over a prominent door. These Rosette carvings were unique in the medieval Irish world but have parallels to examples found in England.

Limestone slabs found at the St Mary’s of Isle site, Cork, dated 12th-14th century.

Effigies were used as part of tombs and became popular from the 12th century. They were representations of the deceased carved on top of a tomb. Two effigies were discovered at the St Mary’s of the Isle site. Displayed alongside the effigies are stone fragments of a sarcophagus found on the same site. It is possible that the effigy lids and stone fragments belonged to the same sarcophagus, although during excavations they were not found as part of their original tombs. The two effigies were used as foundation stones in later walls, which caused damage to their headpieces.

Stone fragments of a sarcophagus found at St Mary's of the Isle site.

Despite damages, we can identify one of the figures as female. The woman is dressed in a robe and wears a brooch necklace, her right hand is raised, and her left hand is to her side. The woman also has a purse and what seems to be a knife. The overall appearance of this effigy is common to other examples from Europe in this period. This effigy could be based on a representation of Margaret of Gloucester, the wife of Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy, who was shown carrying a purse with coins for the poor, and a kitchen knife. The iconography of the Cork effigy could have resulted from the Anglo-Norman influences and the city’s strengthened relationships with foreign cultures through trade and politics.

With the submission of the Irish kings to King Henry II, the role of the High King of Ireland was no longer legitimate. Centralisation of power in England, the rise of feudalism, and the Papacy’s desire to centralise Christendom, eventually caught up with Ireland. With such changes the Gaelic and Hiberno-Norse cultures were forced out of the cities of Ireland and were replaced by the Anglo-Normans, or a mixture of foreign and native cultures. Cork was bound to the continent through its trade and cultural influences. This effigy, showing European trends of the 12th century, is an example of Cork’s wider links to the medieval world.

Porphyry fragment brought back from Rome, recovered from the old Beamish & Crawford site on South Main Street, no date.

Porphyry is a semi-exotic stone that was heavily used by the Romans in decorating buildings because of its vibrant visual impact. Two varieties were common, green, and red porphyry. Porphyry, as an attractive stone which was commonplace in ancient Roman construction, but nearly non-existent elsewhere, served effectively as both proof of a visit to Rome, and a pleasing pilgrim’s relic. Porphyry fragments often showed signs of carvings which had been made in earlier days.

In medieval Christendom, it was common for people to undertake pilgrimages, which were expensive and dangerous journeys to religious sites. In the late medieval world, there were two most prestigious locations to visit. These were Rome, the capital of the Christian faith and the home of the Holy See; and Jerusalem, which between the late 11th and 15th century was controlled by either Christian Crusaders or Muslim rulers.

As with modern tourists, medieval pilgrims often sought to bring back a record of their journey: a token, a relic or even a fragment of a building in memory of their visit. Fragments of porphyry have often been encountered in religious sites within Ireland, suggesting that pilgrimage to Rome was undertaken either by members of ecclesiastical orders or lay people who were buried on the ecclesiastical site.

A pilgrimage badge from Canterbury, made of what is likely lead, dated back to the 12th century. The badge depicts St. Thomas crossing from France to England in a ship. It was acquired as a testimony of a successful pilgrimage to the saint's shire in Canterbury.

On display with the porphyry fragment is a token of pilgrimage: a badge depicting St Thomas Becket. As popular souvenirs, these badges were easy to produce and the Canterbury badge is an example of a pilgrimage token associated with a site that became frequently visited after the canonisation of Becket in the late-12th century. These badges allowed pilgrims to not only identify themselves as devout travellers, but also showed their devotion to a particular saint, and acted as a memory of their journey. Because Cork was a port-town, many pilgrims departed from it on their journey to holy places.

With the increasing popularity of the Canterbury pilgrimage, it is no wonder that such an item would make its way to Cork, but there was also a likely foreign pilgrim presence in the city at the time. The city’s patron saint, St Finbarr, founded a local monastery in 606, and there is a pilgrimage site associated with him at Gougane Barra. There were also pilgrimages to Our Lady of Graces in Youghal, an ivory plaque depicting the Virgin Mary and Christ, dated to the 14th century. Another local pilgrimage site, dedicated to St Gobnait, was located at Ballyvourney, where according to tradition Gobnait found nine white deer following a divine message. A 6th century saint, Gobnait’s influence spread across the south of Ireland from Dingle to Dungarvan in later centuries.

Paternoster amber rosary beads. Sourced from the Baltic region, but probably crafted in Ireland. (and detail below)

Alongside these pilgrimage artefacts, on display, there is a set of paternosters rosary beads, that demonstrate the importance of religion and devotion in the city. These Cork beads, together with examples from Waterford are regarded as the oldest surviving beads of that type in Europe. These beads are made from amber, sourced from the Baltic region, and it can be assumed that Cork had a healthy trade network with the continent to access such materials. There were specialised amber workers in France in the Middle Ages, but these Cork beads were probably crafted in Ireland.

Further Reading:

Harbison, P., Pilgrimage in Ireland: The Monuments and the People, Syracuse University Press, 1995.

Kelleher, H., McCarthy, F. & Brett, C. (ed.), Cork City's Burial Places: A Study of the Cemeteries, Graveyards, and Burial Places within Cork City, Cork, 2011.

Understanding Craftsmanship and Trade Through Artefacts

by Emmanuel Alden & David O’Mahony

The key to understanding the diverse range of medieval artefacts discovered in Cork is to know the roles played by craftsmen, with their specialised skills and by merchants, whose ships brought various products and goods from continental Europe. While much of the labour which supported the city was performed by skilled artisans, the city could not have prospered without the steady importation of raw materials, and of luxury goods from abroad. As a result, the mercantile class, which monopolised the city’s trade, held a controlling stake in the governance of the city throughout much of the medieval world.

Selection of pottery and ceramic pieces found in Cork and the locations of where they came originally came from in Europe

Although most of the raw material used by Cork’s craftsmen was sourced locally, many artefacts that have been uncovered during the archaeological excavations in Cork City show the extent of trade with the wider European world.

Amber, a material which was usually sourced around the Baltic Sea, had been imported into Ireland already prior to the Viking Age - but importation was dramatically increased within a Viking context, as they established trading cities such as Dublin in Ireland, Hedeby/Schleswig in Holstein, Kaupang in Norway and Birka in Sweden. Amber continued to be imported into Ireland throughout the medieval period, as shown by the amber rosary beads discovered during archaeological digs in Cork.

Some of the stone, used in the construction of the Priory of St Mary’s of the Isle, was imported from England. In the 12th and 13th centuries, English Dunbar stone was valued above local stones, as it was easier to carve intricate details into it, and was rather durable, nevertheless, in time it fell out of favour, and later modifications on the building were made using locally sourced limestone.

Lids, spouts and handles.

These objects were excavated from the South Main St, Christ Church, Grattan St and Kryl's Quay excavation sites. It includes different types of Saintonge ware, Ham Green and Redcliffe types.

Pottery fragments are among the most common medieval archaeological finds, and most easily identified artefacts found during excavations. Pottery recovered from the South Main Street archaeological sites included fragments that originated in many of the coastal regions of Europe, such as areas of modern England, Belgium, France, Spain and Portugal. Dating from the medieval and early modern periods, these fragments show that international trade remained a significant feature in the life of Cork throughout its history. However, while it is the pottery shards themselves which survive in the archaeological record, it was not so much pottery that was imported, but rather the goods held in pottery containers, especially food such as fish and preserved fruits, and liquids, including wine and olive oil.

To purchase such imports, Cork developed a heavy export trade, primarily focused on agricultural products, such as grains, and animal products, such as wool, hides and furs and dairy. Because the city relied so heavily on the importation and exportation of goods and materials around Europe, a strong mercantile class prospered and held control over the city throughout much of the medieval period. Some merchant families were able to maintain their position within society for generations - at the start of the 14th century, one prominent Cork Merchant, John de Wynchedon, bequeathed an immense fortune to his heirs. His son, Richard and grandson John de Wynchedon, would carry on the success of the family, holding important positions within the governing body of the city into the mid-14th century.

Selection of objects on public display at Cork Public Museum, including a Norwegian Ragstone, Pilgrim's Badge from Canterbury, a Porphyry Fragment and a clay pipe from Bristol

Objects uncovered from Cork’s medieval sites not only highlight trade links to foreign places but also show the skill of Cork’s local artisans. Like other cities, Cork was home for the usual medieval tradesmen: blacksmiths, leather workers, carpenters and pottery workers. However, with the coming of new materials and new skills, more specialist craftsmen emerged. This process was an outcome of the unique culture that developed in the city under the influence of the native Irish, Hiberno-Norse and Anglo-Norman peoples. Much evidence for the presence of specialised craftsmen has been found in the Christ’s Church area and on the South Main Street. Many objects they produced can be considered luxury items and were used for entertainment or leisure purposes.

Objects made of wood, antler and bone found at the Christ Church and South Main St sites. Included are weaving tools, needle cases, buttons, beads, fishing float, arrows, weaving tools, combs, keys, spindle wheels amongst other objects unearthed.

Miscellaneous objects found at the Christ Church and South Main St sites. These include barrel locks, handle, scissors, needles, knives, keys, mirror cases, buttons, broaches coins, ring, iron shears and a candlestick

These artefacts also demonstrate the increasing need to accommodate a growing city population with many interests. Cork was originally dominated by the Hiberno-Norse culture reflected in its crafting style, but it was diminished with the arrival of the Anglo-Normans and the establishment of the city walls. The Anglo-Normans brought with them increased interests in gaming, beauty maintenance and other luxury goods. The desire for luxury goods after their conquest spurred the development of skilled crafts. The use of amber as a material in the making of rosary beads shows an attraction to aesthetics, even in the ecclesiastical world. The interest in new materials could also stem from the growing contacts between Ireland and Rome, whose lavish ecclesiastical art may have impacted the church in Ireland.

Leather shoes. The lack of oxygen within the layers of excavation is responsible for the good preservation of the leather and other organic material. These objects indicate a thriving leather industry in Cork and evidence of cobbling and shoemaking. Different types of leather footwear found in Cork include ankle-boots/shoes and boots. All of the medieval leather footwear displayed here was found during the Christ Church excavations.

Woodworking and shipbuilding were also acclaimed trades in Cork. The pole lathe was a specialised tool used by carpenters. Archaeological records of Christ’s Church excavations mention an item that may have been part of a pole lathe, and a similar artefact was found in medieval Waterford. The method of pole lathe carpentry was a specialised skill which endured throughout the centuries, having been practiced locally until the 20th century. The method involves partially working the wood on the lathe and then leaving it to dry in the sun for a period before finishing.

Human faces as pottery decoration show how people wanted to portray themselves. The human faces found on medieval pottery ware often less formal, stylised and more humorous than faces found on objects such as coins, wall paintings or tapestries. Medieval jugs often feature bearded men and although the exact meaning has been lost over time, archaeologists suggest that they might have been made for use in secular rites of passage, perhaps related to boys coming of age or that they might relate to stories brought back by people returning from the crusades and depict stylised images of inhabitants of Palestine.

These objects were excavated from the South Main St, Christ Church, Grattan St, Kryl's Quay and Skiddy's Castle excavation sites

Sources of the Christ’s Church area record forty-four combs, which were made from antler bone. Many different types of saw for cutting bone were also discovered at the same site, an indication of local craft rather than importation of bone items. Although there is no known evidence for bone workshops in Cork, it needs to be remembered that much of the medieval city has not been excavated, and evidence for specialised craftsmen have been found in other Irish cities.

Medieval 'cabinet of curiosities' on display at the museum. The public are encouraged to access these drawers on their visit

Further reading:

Gleeson, C.M., A Social Archaeology of Anglo-Norman Cork, NUI Galway, 2015.

O’Brien, A. F., ‘Politics, Economy and Society: The Development of Cork and the Irish South-Coast Region c. 1170-1583’, in Cork History and Society: Interdisciplinary Essays on the History of an Irish County, edited by P. O’Flanagan and C. Buttimer, Geography Publications, 1993, pp. 83-157.

This special online exhibition has been compiled by

Emmanuel Alden, BA in History from Kutztown University, Pennsylvania. He is presently an MA student in Medieval History, University College Cork.

David O’Mahony, BA in History & Geography from University College Cork. He is presently an MA student in Medieval History, University College Cork.

All images by Dara McGrath for Cork Public Museum

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our lecturer Dr Małgorzata D’Aughton for overseeing our projects throughout the semester and for her editorial assistance in this online exhibition. We would also like to thank Daniel Breen, Curator of the Cork Public Museum for allowing us this opportunity to work with the Museum resources on the project and for patiently accommodating us during this turbulent period. Lastly, Emmanuel Alden would also like to provide his thanks to Sara Wingert, MA in Archaeology, UCD, for information and personal comments on the use of dice in the medieval world.

This project is funded by Fáilte Ireland, Ireland’s Ancient East and Cork City Council.

![]()

.

.