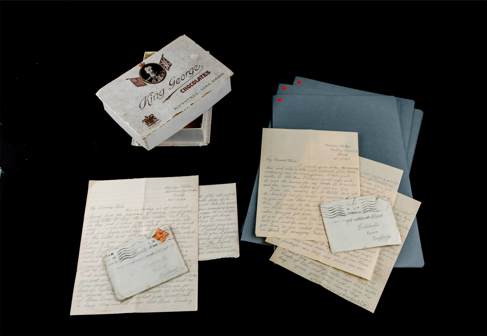

Cowin Letter Collection

(Above) The Cowin Collection of letters.

Click on this link to view all the letters

The Cowin Letters

Background:

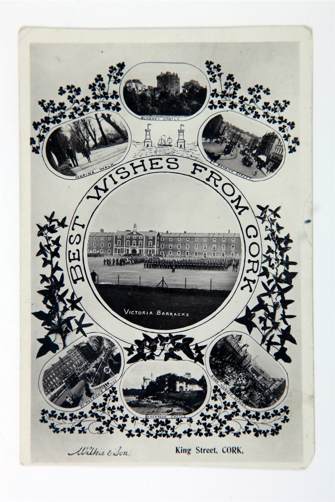

In early 2023, the museum received a very interesting collection of letters from a member of the public in Scotland. The donor, along with his late wife, had actively purchased letter collections from eBay over the years with the purpose of returning them to the families of the original authors or recipients. They were successful with several collections they had purchased but were unable to find any surviving family for the letters that are now donated to the museum. The collection consists of thirty-one letters that were addressed to a Ms. Elsie Lambert who lived at 76 Albert Street, Colchester in Essex. The letters were composed between 20th November 1921 and 20th January 1922 and addressed from the Wireless Station in Victoria Barracks, Cork and were signed by ‘Herbert’.

What makes these letters interesting is the fact that they were composed at a turbulent and transitional period in Irish history. The Irish War of Independence has only ended four months before in July 1921. Negotiations began in October between the government of the United Kingdom and representatives of the Irish Republic, which would eventually lead to the Anglo-Irish Treaty being signed on 6th December 1922. Throughout December and into January 1922, the Irish government debated the Treaty’s terms and the Dáil narrowly approved it on January 7th. Therefore, the letters offer a unique perspective of this time from the point of view of an English person living in Ireland.

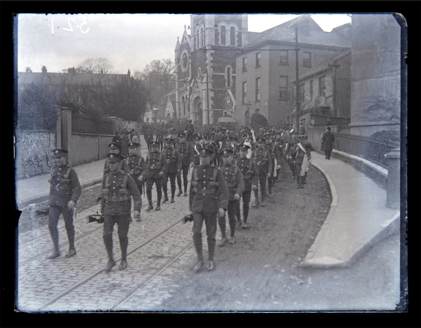

(Above) British military departing Collins (Victoria) Barracks at St Lukes

Who Wrote the Letters?

The first task was to try and identify who the author of the letters is. Reading the contents gave us some details that allowed us to trace the person through available online records. It was apparent from reading the letters that Herbert also lived in Colchester, like his fiancée Elsie. They were both 24 years of age and both still lived at home with their respective parents. The contents of the letters also make it clear that Herbert and Elsie came from a working-class background where unemployment and the cost-of-living concerns were never far from their minds. It was also fortunate that the UK 1921 Census records were only recently released online so this made tracking the author of the letters easier.

Initially, it was believed that Herbert was a member of the British Army serving at Victoria Barracks, but it quickly became obvious that he was a civilian engineer employed by the War Office to help maintain and repair signalling equipment and engines belonging to the British Military in Cork. After some digging, we located a Herbert Crossman in the online digital records who seemed to match the person we were looking for. Born in 1896 to parents Herbert and Alice Crossman of 4, New Quay, Colchester, Herbert had three sisters and a brother ranging in age from 25 to 13. In the 1921 census, he is listed as an ‘engineer’s fitter’ but was currently out of work. His fiancée, Elsie Lambert, also born in 1896, had one sister and lived with her widowed mother, Lydia. She was listed as a tailoress at Everett & Sons, Tailors but was unemployed at the time of the census. This information prompted the question: why did Herbert Crossman find himself in Cork?

Why was Herbert Crossman in Cork?

The simple answer is, he needed a job. The Great War had a devastating impact on the British economy, its industries, labour force and its GDP. Millions of returning demobilised servicemen also contributed to high unemployment rates – it climbed to 23.4% in May 1921. Herbert stated as much in his 7th December letter, when he hoped his job in Cork would be extended as “it’s not much good expecting to find work in England yet and I would rather be here dearie in work than at home walking about”, (Letter 2023.29.10A). In an earlier letter, he suggests if he could get a job at Fords, where he could earn 7 to 8 pounds a week, she could move to Cork (when things calmed down) and they could save enough to get married (Letter 2023.29.8A). Despite the forced separation between them, Herbert tells Elsie that the ‘money would be worth stopping here for’ as similar jobs in his trade in England paid very little (Letter 2023.29.11A). In another letter, (Letter 2023.29.28A) Crossman laments that he should have come to Cork six months earlier as he would be earning more money now. Crossman’s decision to come to Cork was therefore motivated by the dire employment prospects in the UK and his, and Elsie’s, desire to settle down and start a family.

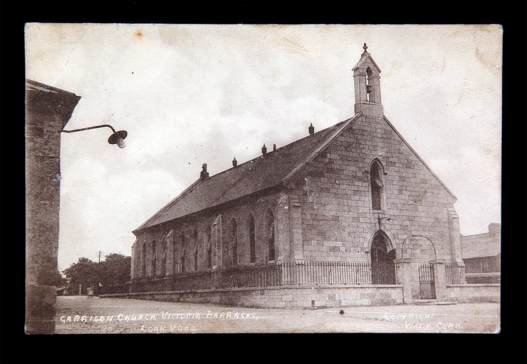

(Above) Postcard :Garrison Church Collins (Victoria) Barracks

Civilian Life in Victoria Barracks:

Crossman took up his position in late October 1921 but does not give many specific details in his letters about the technical side of his duties, but it is clear he was required to travel (by train and/or boat) to other signal stations and locations around Co. Cork to carry out the required repairs and maintenance. He was billeted with other civilian employees at the Barracks and described to Elsie his typical day in the Barracks as follows:

“Len (his friend) and I usual get up about half-eight and then go to breakfast after which we start work for half nine or ten, leave off at twelve for dinner + then start about half two until half four or five. I say we work those hours dear but the last few days we haven’t soiled our hands hardly…”(Letter 2023.29.7A)

Crossman also gives an idea of his weekly expenses:

“Firstly, there is extra messing money and then laundry and then food we buy for supper and stamps and paper soap and boot polish and goodness knows what and after all I only draw £2.17.0 so it doesn’t leave me much for tobacco and a cup of coffee at the Y.M.C.A. for supper.” (Letter 2023.29.31)

Crossman and others working with him relied on packages of food, clothing and cigarettes being sent from home as their wages would not stretch that far without support from the Homefront. He did note that one of his colleagues was sending their laundry home to Aldershot to be washed and mended as it was cheaper than getting it done in Cork, (Letter 2023.29.1).

As it got closer to Christmas, he refers to the food in the mess being “not as good as it used to be” and that he, and the other employees, were seriously considering sourcing food from outside the barracks (2023.29.24A). He seemed to have built a good bond with his civilian colleagues. On the occasion that his waistcoat was stolen, he wrote that, “the fellows in our billet” did not steal it as he “could leave money or anything else laying around for weeks and they would not touch it” (Letter 2023.29.4). He puts the blame squarely on an unknown soldier who took it while he was using one of the soldiers’ washrooms.

It becomes very clear from the letters that Crossman and some of his colleagues did not hold many of the military personnel in high regard. This seems to come to a head in his St. Stephen’s Day letter when Crossman describes that the mess staff were too drunk to prepare food for them over Christmas. Indeed, there had been nothing but “boozing down our mess” and when they went to the mess on Christmas Day night to ‘see a bit of a concert’, they were met with a ‘drunken orgy’. He notes that another drinking session was kicking off as he was writing his letter home to Elsie. He states there was “no enjoyment here for fellows who don’t drink much at all” (Letter 2023.29.24A).

Passing the time at Victoria Barracks:

So, how did Crossman and his colleagues entertain themselves while stationed at the barracks? Aside from occasionally visiting the mess for a drink, there were several options available to them both on and off-site. Dances or concerts, for example, were organised in the Barracks but they brought their own issues and were not always welcoming to the civilian staff:

“I believe the R E’s (Royal Engineers) are having a dance here soon dear and I have heard that their dances are the best in the Barracks…. [but] although they have a military band…they let in all privates and their girls which you can guess are not much class. Of course, sometimes the sergeants have dances, but they only allow their own special pals and all other civilians are barred. There was a posh dance here the other week for officers and such like and there was an ordinary one on Thursday night lasting till about four in the morning but none of our chaps went because they saw they are too common. The dances are held in the Gymnasium which is the biggest floor in Cork and one of the best too.” (Letter 2023.29.12A)

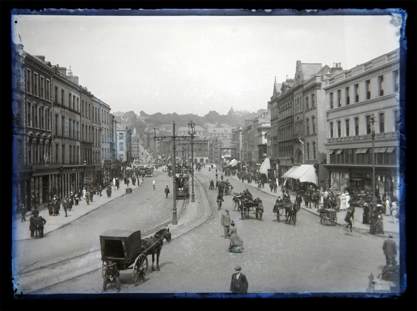

(Above) Postcard: Collins (Victoria) Barracks

It is apparent from the letters that Herbert and Elsie enjoyed socialising and dancing in Colchester prior to his posting to Cork. However, because of the lack of dancehall options at the Barracks and in Cork, Crossman and his colleagues would instead listen to music in their billet and learned new dance moves such as the ‘Palace (Palais) Glide’ and the ‘Happy Walz’ (Letter 2023.29.12A).

Crossman enjoyed reading to pass the time and spent most of his evenings writing letters home to his family and fiancée in pencil by candlelight. In one letter while reassuring Elsie that he did read her letters and had kept them all, he mentions that he would need a “blessed great trunk to keep them all in when I come home”. He is worried he would not be able to fit them all in his case and asked if she would be okay with it if he could burn them or would she “rather that I kept them and tied them up with blue ribbon”, (Letter 2023.29.28A). Writing letters home helped pass the time and was an important means of keeping in touch with loved ones, as well as keeping spirits up until seeing them again.

Crossman and his roommates regularly ventured into Cork City to go for a walk, do a little shopping, or visit the local entertainment establishments. They went to a local variety show in the Cork Palace of Varieties (The Everyman) on Christmas Eve and regularly visited Cork’s many cinemas to enjoy a film. He saw a silent American Western drama film called Rivers End (1920) in the Pavilion, which he considered the best cinema in Cork City. He did not think much of the Coliseum Cinema and could not even remember the film he saw there (Letter 2023.29.7). He watched Of Modern Salome, (made in 1920) that was based on an Oscar Wilde play, at the Cameo cinema (Letter 2023.29.11). The Cameo was opened on 23rd September 1920, and was located on Military Road, opposite Victoria Barracks. General Strickland, Commander of the 6th Division in Ireland, was a frequent visitor to the Cameo.

Crossman’s Views of Cork City, its People, Language and Current Political Situation:

Crossman gives very little detail about the geography or landscape of Cork City but from some lines found in these letters, you get the impression that he did not have an overly positive opinion of the place. In early December, he writes:

“…we walked down the town as usual in the afternoon and paid our usual visit to Woolworths and had a look round the shops and I must say that the shops looked very nice, in fact better than they looked ever since I have been here”, (Letter 2023.29.14A)

Being an ordinary British civilian rather than military personnel allowed Crossman to move through Cork City unmolested, but he was quick to point out to his concerned fiancée that he avoided “rough parts” and that it was “safe enough if you don’t keep looking about as if you are spying on them”, (Letter 2023.29.5A). Crossman found it strange to “walk along the streets and not see anybody you know and to hear everyone speaking in Irish” and admits that people may as well be speaking “Spanish or any other blessed language” for all the chance he had to understand them. He bluntly states that the “Irish Brogue is simply awful” (Letter 2023.29.5A). On another occasion, he remarks that there “is not a great deal of green worn here dear, although it’s the national colour” (2023.29.4A)

(Above, left and right) General views of Cork c.1920

In another letter, Crossman tells Elsie that he “can’t have you throwing out this sarcasm about Blarney because I sure don’t want to kiss that dirty old stone and as for kissing and marrying an Irish girl, I don’t think it matters. Give me an English-speaking girl every time for I am sure there are none better. Some [girls] you hear talking as you pass, seem to be talking French or German or something like that and I should fancy they were swearing at me always” (Letter 2023.29.12A)

Though Crossman rarely refers directly to the Irish and British political situation during his stay in Cork, he does make brief allusions to what was happening in Victoria Barracks and the wider community. Most of his references, however, are in the context of his continued employment and the amount of time he would have left in Cork. In early December, he writes “What do you think of the Irish peace settlement dear, I shouldn’t be surprised if this job doesn’t last much longer…” (Letter 2023.29.10A). The following week, just two days after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, he repeats that he wouldn’t be “surprised if you see us home before long dear now that the peace question is practically settled anyway, nearly all the fellows in our room have got the wind up as not any of them want to lose a good job like this” (Letter 2023.29.15A).

He also refers to changes in personnel at the Barracks in preparation for the eventual handover to the Irish Free State. On December 30th, he mentions that “24 Irish labourers” were sacked from the Barracks and he saw this as a general wind down in operations (Letter 2023.29.27A). In early January, he reports that many of the Royal Engineers were being sent to India from Victoria Barracks and that it “looks a bit more lively for us civilians as they still want somebody to fill their places, at least those who were on our sort of work” (Letter 2023.29.28A).

British authorities began the process of withdrawing Crown Forces from Southern Ireland after the Dáil approval of the Treaty in January 1922. The speed of this withdrawal was not uniform and varied across the country depending on the realities on the ground. Despite the Treaty, it was still a dangerous time to be a British soldier in Ireland as many were killed during 1922. In Cork, for example, Lt Henry Genochio of the Royal Engineers, was abducted and killed by the IRA on the night of 15th February. It is believed that he worked in Intelligence and was killed for his part in previous operations against the IRA in Limerick.

(Above, left and right) General views of Cork c.1920

In his letters however, Crossman makes only one reference to the wider tensions in Cork at the time. In his 27th November letter, he mentions a photo of the “Cork funeral” that Elsie should look at from last “Wednesday’s Mirror” (Letter 2023.29.7A). The dates would indicate he was talking about the funeral of Tadhg Barry, a well-known and respected trade unionist, Irish nationalist politician, founding member of the Cork Brigade of Irish Volunteers and GAA stalwart. He was shot in Ballykinlar Internment Camp on 15th November and his funeral was one of the largest ever seen in Cork, receiving worldwide media coverage.

One final interesting reference is found in his 1st December letter, in which he writes that he was “quite surprised to hear about those Leinsters making a lot of trouble” in Colchester (Letter 2023.29.10A). Numerous newspapers report that on the night of November 25th, three young soldiers from the Leinster Regiment were arrested and charged for a drunken rampage and chase through the town that included attempted robbery, assault and property damage. They threatened one individual by telling him that “We kill such [obscenity] as you in Ireland” in reference to the well published assassinations carried out by the IRA during the recent War of Independence. Crossman was shocked by their actions and thought they were a “loyal regiment” and warned his fiancée to be careful when out in Colchester as “you never know what Irishmen will do for half of them are too ignorant to know better” (Letter 2023.29.10).

Crossman was aware of the dangers he potentially faced, as an employee of the British military in Cork but he displayed no real interest in the Irish Question, the Treaty, or the future of British and Irish relations. He offers no comment on the conduct of the Irish War of Independence and does not even mention the obvious scars left on the city’s main thoroughfare following the Burning of Cork by the Auxiliaries in December 1920. For him, being in Cork was a necessary and justified risk to ensure he could earn money to create a better future for himself and Elsie. The realities of unemployment and economic stagnation in the UK were of greater concern to him than Anglo-Irish relations and history.

(Above) Postcard from Collins (Victoria) Barracks

Long-Distance Relationship:

Despite the historical interest and unique insight, the letters provide, they are, ultimately, a personal correspondence that portrays a young couple enduring the ups and downs of maintaining a long-distance relationship. Frustration, jealousy, loneliness, longing, and love permeate through the letters as Herbert and Elsie navigate the emotional pitfalls of living apart. They are a working-class couple who, while still living at home with their parents, are desperately hoping to earn enough money to start a life and family of their own:

“I’m surprised at you saying you will be glad when this job is finished, surely its better than being out of work at home isn’t it?” (Letter 2023.29.19)

Being apart was difficult at times, especially for Elsie, as we learn, through the letters, of numerous family members and friends getting engaged, married and having children while they were stuck in a four-year engagement. Adding to this tension was the fact that it was their first Christmas apart and Elsie was keen to have Herbert home for Christmas, even offering to pay his fare. Despite the obvious sadness at their separation, Crossman seeks to reassure Elsie that she seems “to think I don’t love you now dear but I am not clever at expressing my feelings on paper so you will forgive me won’t you dear but you know I love you as much as ever dearie…” (Letter 2023.29.21A)

(Above) Britishh soldiers remove thhe main flagpole, prior to their departure

In one of the last letters in the collection, Crossman promises her that he will be home soon, and they can concentrate on setting up their new life together:

“I can’t help us being nearly 25 and being engaged for four years. I wish I could but look at the luck I have had this last year or two, it’s been all spending and not much coming in, but I hope our time will come soon and then we won’t be long getting married as you have got practically all you want in the way of house linen” (Letter 2023.29.28A)

Thanks to available online records, it was confirmed that Herbert and Elsie did in fact get married a year later, on 29th December 1923, at St. Peter’s Church in Colchester. They would live most of their lives until the 1960s in numerous locations around Reigate in Surrey. They would have one son, Brian, who was born in 1936. More research is needed to fill in some gaps, but this unique letter collection gives us a very different ‘outside’ perspective on such an important period in Cork’s history.

To read the original letters, please click on this link: https://publications.corkpublicmuseum.ie/view/1046548220/

Further Reading:

Walking Wounded: The British economy in the aftermath of World War I by Professor Nicholas Crafts

British Withdrawal from Southern Ireland in 1922

http://kieranmccarthy.ie/?p=19377