The Internationalisation of the Irish Revolution

Dr Jeff Kildea, who is writing on Australia in this project, is an adjunct Professor of History at the University of New South Wales. A retired barrister, he held the Keith Cameron Chair of Australian History at UCD

The Internationalisation of the Irish Revolution – Irish Diplomacy and global resistance to the British Empire, 1916-1923

Dr. Mervyn O’Driscoll, Head of School of History, UCC, Dr Dermot Keogh, Emeritus Professor of History, UCC and Dr. Owen McGee.

Professor Joe Lee put it very simply: ‘No America, No New York, No Easter Rising.’ Applying that argument for the period 1919-1923, one might equally say ‘No Irish diplomats, no Irish diaspora, no Irish Catholic church abroad, then no independent Irish state and no national sovereignty.

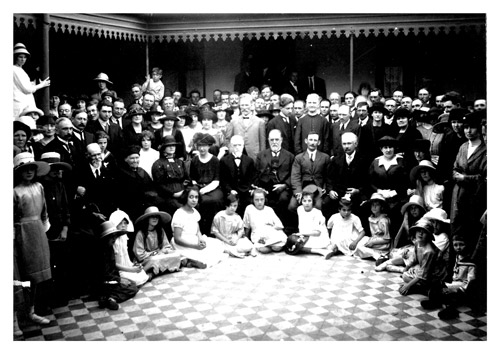

Above: Dáil Éireann envoy Laurence Ginnell and his wife Alice (front centre) at St. Patrick's Day celebrations, Venado Tuerto, Argentina, March 1921 (courtesy of Roberto Landaburu)

This project, rooted in a theme I have been working on for over fifty years, does not see the domestic and international struggle for Irish independence as two separate entities. In the mind of that revolutionary generation both were organically linked. It was the genius of the leadership to prioritise the mobilisation of the Irish abroad and democratic and nationalist movements around to world in defence of the case for Irish independence while, at the same time, highlighting the ever increasing repressive tactics being deployed by the British government.

Above: The Republic of Argentina stands in solidarity with Ireland recognising the latter's right to self-determination

When Dáil Éireann was established in January 1921, the new Irish government set up a Department of Foreign Affairs to help win international recognition for the new Irish State. President Éamon de Valera spent eighteen months in the United States, from June 1919 until December 1920, rallying support for the recognition of the Irish state. He was supported by women and men, diplomats by accident, who volunteered to provide him with professional help and this was also the case in the Irish diaspora and in many capitals of the leading powers in different parts of the world – in Britain, continental Europe, South Africa, Argentina, Australia, New Zealand etc.

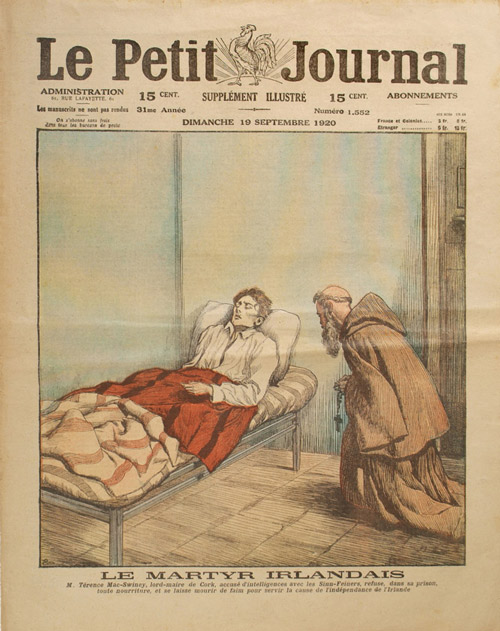

The death of the Lord Mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwiney, in Brixton jail on 25 October 1920 was the tragic event in those years of conflict which most captured popular and press attention all over the world greatly motivating and mobilising the leaders of the Irish diaspora to raise their voices globally against what was happening in Ireland and to support the right to national sovereignty.

Above: This rare medal commemorating Terence MacSwiney was minted in Buenos Aires in 1920. A silver version was presented to the Cork Public Museum by Eduardo CLancy in 2017 and Dermot Keogh presented one in bronze on the same occasion.

While the struggle to internationalise the Irish revolution has been well covered for the United States and Britain, this project brings together a team of scholars from around the world who will highlight the global reaction to the struggle for Irish independence both in countries with a strong Irish diaspora and in those with anti-imperialist traditions in Europe, the Americas, Africa, Asia, Australia and New Zealand.

Above: Professor Dermot Keogh

Dr. Mervyn O’Driscoll, Head of School of History, UCC, Dr. Owen McGee and myself will between 2021 and 2023:

- host on line a series of talks, seminars and a conference;

- collect photographs, posters and images from around the world which will be put up on a website together with key documents;

- and edit a volume of essays highlighting the work of women and men who served in different countries abroad during those years of revolution.

- Dermot Keogh, Professor Emeritus, UCC.