(Above) A early 20th century view of Sunday’s Well, looking westward on Sundays Well Road.

Sunday’s Well is a suburb located in the north-west of the city, on a ridge on the northern bank of the River Lee. It takes its name from an ancient holy well once located there known in Irish as Tobar Rí an Domhnaigh (Well of the King of Sunday), referring to Jesus Christ as represented in the Catholic Church.

There are many references to the well in historical sources. The oldest is believed to be found in a Middle Irish tale of anonymous authorship, probably written in the late 11th/early 12th century entitled Aisling Mic Conglinne. This satirical story is set in the decadent days of the St. Finbarr’s Cork monastery where the main character is taken to a well named Bithlán, or Ever-full. This has been identified at Sunday’s Well.

In 1644, a French traveller, Francois de la Bouuaye le Gouz, came to Ireland. On a trip to Cork, he noted: “A mile from Korq is a well called by the English Sunday spring, or the fountain of Sunday, which the irish believe is blessed and cures many ills. I found the water of it extremely cold’. In Smith’s History of Cork (1774), reference is made to ‘a pretty hamlet, called Sunday’s well, lying on a rising ground, and command a view of the city and river. Here is a cool refreshing water, which gives name to the place; but it is hard, and does not lather with soap...”

According to John Windele (1839), well known antiquarian and historian, the origin of the well is much older than its Christianised name suggests: ‘It takes its name from one of those ancient fountains, which, long ere the Christian faith was preached in Ireland, was held sacred by its Druids and people. The exertions of the first missionaries were ineffectual to prevent their worship, and they had to content themselves with diverting the popular devotion, and substituting objects of Christian reverence. Sunday's Well, in Irish, " Tobar Righ an domhnach," i. e. the fountain of the Lord, is one of those converted shrines.”

Windele also described how on early Sunday mornings in summertime, pilgrims would make their way to the well as penance and tie rags to the trees around it. He claims the water to be clear and wholesome and states the Smith was incorrect to suggest the water did not lather with soap.

(Above) This late 19th century of the holy well that gave its name to the area. Notice the boy with his bucket, possibly used to collect water from the well.

At some stage in its past, a stone structure was constructed over the well with stone steps running down to the water. Windele describes it as a “small circular building, capped with a stone, and shaded by an elm and two ash trees”. Thomas Crofton Croker, well-known antiquarian and author/researcher of Irish folklore and music visited the well in and around 1845. This visit was commemorated in some verses written by Father Prout (penname for humorist and journalist, Francis Sylvester Mahony).

In yonder well there lurks a spell,

It is a fairy font;

Croker himself, poetic elf,

Might fitly write upon’t.

The summer day of childhood gay

Was spent beside it often;

I loved its brink, so did, I think.

Maginn, Maclise, and Crofton.

Of early scenes, too oft begins

The memory to grow fainter.

Not so with me, Crofton, nor thee,

The Doctor or the Painter.

There is a trace time can’t efface,

Nor years of absence dim –

It is the thought of yon sweet spot,

Yon fountain’s fairy brim.

The structure over the well remained in place until it was demolished in 1946 as part of a road-widening scheme. Fortunately, Professor of Archaeology at UCC and Curator of Cork Public Museum, M J O’Kelly excavated the well prior to the commencement of the road works. During the excavation, O’Kelly unearthed evidence of a midden against the wall behind the well, between 15–30 cm in thickness and about 12 mtrs in length. O’Kelly summed up the evidence as follows:

“The layer was made up mostly of shells of the common oyster, and bones of ox, sheep and pig, many of them obviously deliberately split to facilitate the extraction of the marrow. There were evidences that fires had been lighted and it was possible to ascertain that the midden was modern because of the occurrence all through it of sherds of glazed pottery, typical of the 17th and 18th centuries A.D.”

(Above) Another early 20th century photo of the well. The site has obviously been landscaped since the earlier image as the trees that once flanked the well have been removed. There has also been the addition of a vent to the top of the well structure

O’Kelly believed that due to the midden’s stratigraphical relationship to the well, it is possible that pilgrims who visited the holy site left behind the material in it. It is also more than likely that locals would have also used the well for washing and cooking instead of taking the water from the river.Today, the site is marked by a simple wall-mounted plaque and an outline in coloured brick on the structure that once protected the well.

(Above left) The site along Sundays Well Rd where the well was located (note the curved paving stones in the foreground marking its exact site)

(Above right) the original plaque that was located on the well is now located on the wall above the well. Marked 'Sundays Well 1644'

The Development of Sunday’s Well

At the time of Francois de la Bouuaye le Gouz’s visit to the area in 1644, Sunday’s Well, though just a short distance from the centre of Cork, was very rural with little residential properties. Compared to life in the overcrowded, dirty and unhealthy streets and laneways of Cork, areas in the outskirts of the city, like Sunday’s Well, proved highly desirable and fashionable for the city’s more affluent citizens to live. They were close to the city but offered the benefits of rural living. It can be said that Sunday’s Well was one of Cork’s first suburbs.

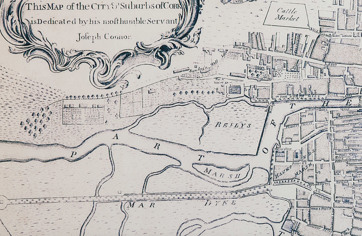

(Above) The Joseph Connor Map (To Hugh Carleton Esq. Recorder of the City of Cork 1774)

Reference the well laid out plots of land devoted to horticultural practice, to help feed the city.

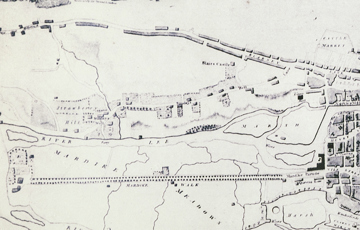

(Above) The Beauford Map (City and Suburbs of Cork according to the latest improvements by W. Beauford 1801)

Reference the residential development of the city was underway and would continue well into the 20th century

In his description of Sunday’s Well in 1774, Smith refers to a ‘pretty hamlet’ and paints a picture of an idyllic horticultural paradise where there were “very great plantations of strawberries, of the largest and finest kind, as the chilli, and the hautboy strawberry. The planters of those fruit, pay considerable rents for their gardens, by the profits arising from them alone, and they have also great plantations of them round other parts of the city.” Windele referred to the area during the 18th century being “covered with the ‘boxes’ and pleasure grounds of the more substantial citizens”. Evidence from old maps of Cork, show Sunday’s Well and environs having plenty of natural wood lands and specially laid out gardens and plots dedicated to growing what much have been a variety of plants, fruits and vegetables. Indeed, the present day place names ‘Strawberry Hill’ and ‘Shanakiel’ (or Old Woods/Old Foxes Wood) hint at the area’s more bucolic past.

(Above) The Buxton (Buckstone) Stone 1760.

Another interesting ancient place name associated with Sunday’s Well is ‘Buxton’. According to Tuckey in his Cork Remembrancer (1837), Sunday Well’s was known as ‘Little Buxton’ because of its perceived healthfulness. Buxton is said to be a anglicised translation of the Irish phrase ‘Carraigin na Bhfia' – (The Little Rock of the Deer) – Buckstone. Tuckey mentions that there was a stone plaque on the wall of a house in that area that had ‘Buckston 1760’ inscribed on it. The stone was re-discovered in the 1940s during the demolition of a house and now resides in the museum’s collections. It is plausible that the stone is all that remains of a large house that once stood there. The ‘Buxton’ legacy is retained in the area today with the place names ‘Buxton Hill’ and ‘Buxton Terrace’.

The nineteenth century saw increased infrastructural and residential development in the Sunday’s Well area. There was a surge of house building for middle class families. Many of the large houses that exist there today, date to this period. The sprawling lawns with panaromic views of Cork City hark back to the days when Sunday’s Well was a rural suburb.

Many notable landmarks were also built during the 1800s and early 1900s:

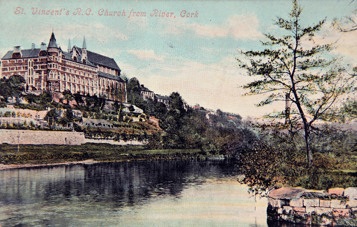

(Above) A view of Sunday’s Well from across the river that shows the grandeur of some of the houses being built in the area by the end of the 19th century. This image shows the area before the construction of Daly’s Bridge. Notice the boats in the background that ferried people across, connecting Sunday’s Well and the Mardyke.

Cork City Gaol was opened in 1824 as a major upgrade to the prison located at North Gate Bridge, which had been in operation since medieval times. Sunday’s Well was an ideal site as it was outside the city and afforded more space as the old jail had become too small and overcrowded. The new prison housed both male and female prisoners who committed crimes within the city boundary. Those who committed crimes outside the city boundary were sent to the County Gaol (located at Gaol Cross beside University College Cork). Cork City Gaol remained in use as a prison until 1923.

(Above) A view of Cork Gaol from the junction of Shanakiel Road and Sunday’s Well.

Wellington Bridge (now known as Thomas Davis Bridge) was built around 1830 to connect Sunday’s Well to the Western Road.

(Above, left and right) Early 20th century views of Wellington Bridge. Notice in the left hand image the attractions and exhibits in the Western Field of the 1902/03 Cork International Exhibitions. This area is now The Mardyke Sports Arena.

(Above, left and right) Several views of St Vincents - how it dominates the landscape.

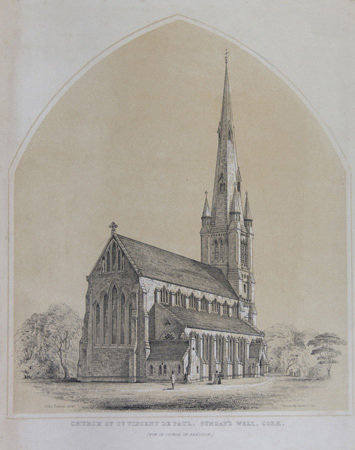

(Above) An interesting Henry Hill sketch showing a spire/tower that was never completed (John Benson architect)

The large and dominating St. Vincent’s Church was opened in the mid-1850s. Built on land that was donated by a local resident Mary MacSwiney in 1851, it commands a sweeping view of Cork city. It was run by the Vincentians but is no longer in use by them today. University College Cork’s music department occupies part of these buildings now.

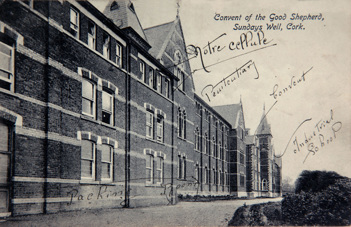

(Above) The Good Shepherd Convent

The Good Shepherd Convent opened in 1872 and functioned as an orphanage and a Magdalen laundry until the late 1970s.

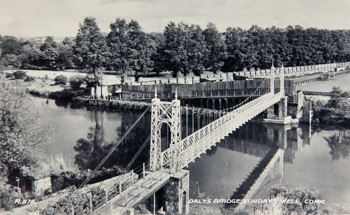

(Above) Daly's Bridge (aka 'The Shakey Bridge')

Another important addition to the landscape that helped connect Sunday’s Well with the Mardyke was the building of Daly Bridge in 1927. Known locally as the ‘Shakey Bridge’, Cork’s only suspension bridge was designed by the Cork City Engineer, Stephen W. Farrington and constructed by London-based, David Rowell & Company. The bridge takes its official name from local businessman, James Daly who funded its construction. The bridge re-opened in December 2020 after an extensive restoration programme.

Prior to the building of the bridge, a ferry service operated to transport people from Sunday’s Well to the Mardyke and vice versa. Today, if you visit the ‘Shaky Bridge’, you can still see remnants of this service with the original steps, moorings, nineteenth century railings, as well as the place name, Ferry Walk.

Special thanks to Catherine Julia Conway for her research and work in creating this article. Catherine, a MA student in UCC Archaeology Department’s Museum Studies course, was on placement at Cork Public Museum in early 2020.

Further Reading: